Revolution #208, July 25, 2010

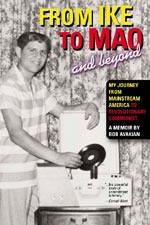

From Ike to Mao and Beyond

My Journey from Mainstream America to Revolutionary Communist

A Memoir by Bob Avakian

from Chapter 1: Mom and Dad

Armenia to Fresno to Berkeley

... My dad's parents emigrated from Armenia, before the big massacre of a million and a half Armenians by the Turkish authorities in World War 1. Even before the war, the Turkish government had carried out and encouraged brutal pogroms against Armenians for many years. My grandmother's and grandfather's families had both suffered from that, and they had left Armenia and come to the U.S. when my grandparents were young, where they met each other and married. So my father was born in the U.S., in Fresno, where his parents' families had settled as farmers because the climate and the kind of crops you could grow were similar to Armenia....

My grandparents were very good-hearted, generous people, and some of my other Armenian relatives were as well. But many of them were also petty property owners and proprietors, with the corresponding outlook. So it was a very contradictory kind of relationship. I was fond of them, because they were relatives and many of them were very kind on a personal level; but, at the same time, many were very narrow-minded and conservative, or even reactionary, on a lot of social and political issues. And from a very early age, because I was raised differently than that, there was a lot of tension, which sometimes broke out kind of sharply.

Fresno was an extremely segregated city, with a freeway through the center of town serving as a "great divide." On one side of the freeway lived all the white people—and essentially only white people lived there. Ironically, the Armenians, who were not actually European in origin, in the context of America were assimilated as white people, even though they faced some discrimination. By the time I was growing up, if you were Armenian you were accepted among the white people, by and large, somewhat the way other immigrants, like Italians, might have gone through some discrimination but finally got accepted as being white.

The Blacks and the Latinos and Asians lived on the other side of the freeway in Fresno, where the conditions were markedly and dramatically much worse. And none of my Fresno relatives ever ventured, at least if they could help it, across the freeway. So this was emblematic and representative of a lot of the conflict that came up. For these reasons, I have acutely contradictory feelings about Fresno and my Armenian relatives.

My dad was very aware of the discrimination against Armenians, and this had a big effect on how he looked at things more broadly. He ended up setting up his own practice, and practiced law with a couple of partners, partly because he couldn't get hired by these other firms, even though, as I said, many of them offered him jobs if he would change his name. I remember his telling a story about when he was on the college debating team. They were traveling to a debate in Oregon, I think, and they went to the house of one of the debating team members for dinner before the debate. So, as people do when they are being hospitable, the family was lavishing a lot of food on the team, and it got to a certain point where the debating team guys were saying, "No, we're full, thank you very much"; and the hosts were saying, "Come on, eat, eat, don't be a starving Armenian." Then all the members of the debating team got this look on their faces, and the parents realized they must have committed a faux pas, and then someone told them what the deal was with my dad. Those kinds of incidents stamped the question of discrimination very acutely into my father's consciousness. Besides learning about this directly from him, I've seen interviews that he's done, or speeches that he's given, where he has talked about the big impact this had on him and how it made him very acutely aware of the whole question of discrimination and the injustice of it. This would carry over importantly into his life, when the struggle around civil rights and the oppression of Black people broke open in American society in a big way in the 1950s and '60s. ...

Compassionate...and Determined

... While my parents were from different backgrounds, neither of their families resisted their marriage. Despite a lot of insularity among the Armenian relatives, my father's parents felt the important thing was what kind of person you marry, not whether they were an Armenian. My mother was pretty readily accepted both because of the attitude of my father's parents, but also because she was a very likeable person. And my mother learned how to cook some of the Armenian foods, and picked up some of the other cultural things. Beyond that, my father would not have put up with any crap! So the combination of all that meant that she got accepted pretty quickly. I'm not aware of friction from my mother's parents toward my dad. They were nice people generally, although they too were pretty conservative in a lot of ways, and also, to be honest, my father, having graduated from law school, was someone who had a certain amount of stature when my parents got married.

Despite the fairly conservative atmosphere in which she was raised, my mother was very far from being narrow and exclusive in how she related to people. If she came in contact with you, unless you did something to really turn her off or make her think that you were a bad person, she would welcome and embrace you. And that would last through a lifetime. Besides things like the Sunday "sacrifice night" meal, my parents, mostly on my mother's initiative, would do other "Christian charity" things, like in that Jack Nicholson movie, About Schmidt, where he "adopts" a kid from Africa and sends money. But they not only paid a certain amount of money, they took an active interest — they corresponded, they actually tried to go and visit some of the kids or even the people as grown-ups with whom they had had this kind of relationship. My mother had a very big heart and very big arms, if you want to put it that way. She embraced a lot of people in her lifetime. You really had to do something to get her not to like you. She was not the kind of person who would reject people out of hand or for superficial reasons.

I remember when I was about four or five years old and somehow from the kids that I was playing with, I'd picked up this racist variation on a nursery rhyme, so I was saying, "eeny, meeny, miny moe, catch a nigger by the toe." I didn't even know what "nigger" meant, I'd just heard other kids saying this. And she stopped me and said, "You know, that's not very nice, that's not a nice word." And she explained to me further, the way you could to a four- or five-year-old, why that wasn't a good thing to say. That's one of those things that stayed with me. I'm not sure exactly what the influences on my mom were in that way. But I do remember that very dramatically. It's one of those things that even as a kid makes you stop in your tracks. She didn't come down on me in a heavy way, she just calmly explained to me that this was not a nice thing to say, and why it wasn't a good thing to say. That was very typical of my mother and it obviously made a lasting impression on me.

One thing I learned from my mother is to look at people all-sidedly, to see their different qualities and not just dismiss them because of certain negative or superficial qualities. And I also learned from my mother what kind of person to be yourself — to try to be giving and outgoing and compassionate and generous, and not narrow and petty. I think that's one of the main influences my mother had on me.

Insight Press • Paperback $18.95

|

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.