Revolution #218, November 28, 2010

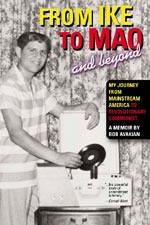

From Ike to Mao and Beyond

My Journey from Mainstream America to Revolutionary Communist

A Memoir by Bob Avakian

from Chapter Nine: Becoming a Communist

At that time, there were just a few of us in our core group in Richmond who considered ourselves conscious revolutionary activists. But we were meeting a lot of people, and people were starting to hear about some of our work and to call us from different parts of the Bay Area, and even other parts of the country, asking about what we were doing. Also, we started hooking up with other people who had similar politics to ours. We were moving more in the direction of recognizing that we had to get much more clear ideologically and in particular that we had to become more firmly grounded in communism and communist theory. So, we were moving in that direction, and we were meeting with, talking and struggling with other people who had similar politics.

At a certain point, we decided that we needed to form some kind of an organized group, not just in Richmond but more broadly in the Bay Area. So I wrote up a position paper, which we took around to other -people, and it became the basis of discussion and the basis of unity, more or less, for drawing people together — originally just a handful — to form some kind of a group. We didn't exactly know what kind of a group. It was still sort of a mixed bag ideologically, but clearly we were for revolution, as we understood it, and moving in a direction of being for socialism and communism, as we were beginning to understand that more fully.

Leibel Bergman

About this time I came in contact with someone who would play a very important role in developing me fully into a communist and in lending more ideological clarity to our efforts in forming the organization that we did form in the Bay Area late in 1968, which we called the Revolutionary Union. That person was Leibel Bergman, who had himself been in the Communist Party in the 1930s, '40s and early '50s. (He had also been in PL for a brief period after that, before deciding that it was not really going in the right direction and could not provide the needed alternative to the revisionism of the CP.) Leibel was a veteran communist, but he broke with the Communist Party in 1956 when they took up the Khrushchev program of in effect denouncing and slandering the whole experience of socialism in the Soviet Union up to that time. Khrushchev did this largely in the form of denouncing Stalin, but this was part of his renouncing the basic principles of socialism and communism. Leibel had criticisms of Stalin, and as we developed our theoretical understanding in the Revolutionary Union we began to deepen those criticisms of Stalin, but we saw that just negating and trashing the whole history of the Soviet Union under Stalin's leadership was going to lead you back into the swamp of embracing capitalism.1

That's one of the things that I came to understand through a lot of discussions with Leibel. He had written a paper criticizing this move on the part of the CP in the U.S., to take up this Khrushchev program. And it wasn't just denunciation of Stalin; along with that, and with that denunciation of Stalin as kind of the battering ram, Khrushchev started promoting his "Three Peacefuls": "Peaceful Coexistence" between capitalist and socialist countries; "Peaceful Competition" between socialism and capitalism; and "Peaceful Transition" to socialism from capitalism. In other words, Khrushchev started promoting the idea that revolution was no longer necessary, that somehow through electoral parliamentary means and peaceful means in general you could achieve socialism — somehow the imperialists were going to allow you to bring into being a socialist society, and ultimately a communist world, without using violent means to try to suppress that and drown it in blood. Leibel rejected that, and he wrote a paper criticizing it which got circulated in the communist movement not only in the U.S. but internationally.

As a result of that, Leibel had been invited to China. So he'd gone to China around 1965, and he was there when the Cultural Revolution broke out. He was there for several years during some of the high points of the upsurge of the Cultural Revolution, and then he came back to the U.S. At a certain point, he approached me and said, "Well, you seem to be very radical-minded and very active, and you seem to be strongly against white chauvinism" (that's the term he used). He thought I had the potential to be a communist, and he decided to work to develop me into one.

I began spending a lot of time with him, and he had a big influence on me in getting me to read more communist theory. I read things like The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. I started reading more than just the Red Book, going further into Mao's Selected Works and other writings by Mao about the Chinese revolution and about communism. I started reading Lenin's writings on imperialism, and his famous work What Is To Be Done?, as well as various works by Marx and Engels (although it would be a few years before I managed to launch into the study of Marx's Capital and — after some initial frustration and difficulty in understanding Marx's method of analysis — I was able to work my way through it and learn a great deal in the process). I was also discussing and struggling over big political and theoretical questions with Leibel.

Leibel would struggle with me — sometimes subtly, and sometimes quite sharply. For example, there was a meeting in Berkeley which had something to do with supporting the struggle of the Angolan people — Angola was still a colony of Portugal at that time, and Angolan revolutionaries were waging an armed struggle for independence. People at this meeting were debating back and forth about Angola and the freedom fight there, and I got up at one point and made this speech supporting the Angolan people's struggle and said: "It doesn't matter if the Portuguese think the Angolans are a nation. It doesn't matter if everybody here thinks the Angolans are a nation. It doesn't matter if I think the Angolans are a nation. What matters is that they believe they're a nation. So they should be able to be free."

Leibel was there at the meeting, and afterward he talked to me about this. He said: "Well, you know, you made a lot of good points, but the way you put it is not right. It's not a matter of what anybody, even the Angolan people, just thinks. It's a matter of what's objectively true, what's the reality. And since it is true that they are an oppressed nation, a colony, then they should be supported in fighting for liberation. But it is not a matter of what anybody thinks. It's a matter of what the reality is." That was a big lesson for me that I've remembered to this day.

Around this time a book came out that had a lot of influence in the radical movement. It was written by Regis Debray, who is now a bourgeois functionary in France, and it was called Revolution in the Revolution. It basically put forward the Castro-Che Guevara line on how you make revolution, particularly in Latin America, and argued that you didn't need a party to lead it, you just needed a military "foco," as they called it — that is, a military force that would be both a political leadership and a military leadership and would go from place to place fighting and supposedly spreading the seeds of revolution.

I was very influenced by this book, and so were many other people I knew. But the thrust of the book, the essential position it was putting forward, was not correct and influenced people in the wrong direction. I recall arguing vigorously with Leibel about this for hours, because I was being swayed by Debray's arguments. And at one point he got very frustrated with me — in the course of this argument, he slapped me on the thigh and said, "You know, you're an asshole" because I was being stubbornly resistant to his arguments, which were actually more correct than mine, and he got frustrated. But finally, I remember the thing that really stuck with me. He said: "This whole line about how you don't need a party is really wrong, because without a party there is no way you can really base this among the people" — he was talking about an armed struggle for revolution in countries of the Third World. I asked why.

"Because," he said, "in order to base it among the people, you have to do political work among the people. You have to organize the people to actually take up economic tasks, to carry out transformations in the economy and meet their economic needs, to make changes in their conditions and their social relations, as well changing the politics, the culture and ideology; and in order to do that, you have to have a political force that isn't just moving around with the army from place to place but is rooted among the people and actually mobilizing and leading them politically and ideologically. The military is a separate force, which may do political work, but it can't substitute for sinking deep roots and leading the people to carry out these transformations. That has to be done with the leadership of a party, and its cadres — it can't be done by an armed force which is made up of full-time fighters, and which has to move from place to place in fighting a war." That was a very profound point; it struck me very penetratingly at the time, and it has stayed with me since.

To be continued

1. Joseph Stalin led the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from the mid-1920s up to his death in 1953. Shortly after his death, Nikita Khrushchev took the reins of power and instituted a form of capitalist rule under a fairly threadbare socialist cover. For more on Bob Avakian's evaluation of Stalin—his overall positive historical role and accomplishments, along with his serious shortcomings and grievous mistakes—see, among other works, Conquer the World? The International Proletariat Must and Will. [back]

Insight Press • Paperback $18.95

|

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.