Revolution #270, May 27, 2012

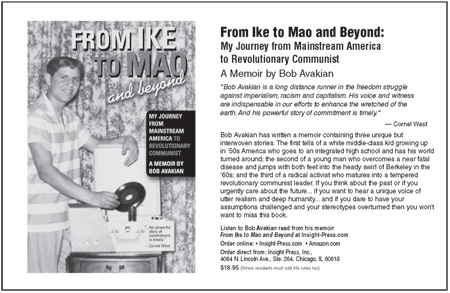

From Ike to Mao and Beyond: My Journey from Mainstream America to Revolutionary Communist, a Memoir by Bob Avakian

from Chapter Four: High School

Basketball, Football...and Larger Forces

At that time, the basketball coach at Berkeley High, Sid Scott, was a Christian fundamentalist. He was always lecturing the players about religion. He was also a big racist. Every year when I was in high school, and even before I got there, the starting team would always be three Black players and two white. My friends and I used to always talk and argue about why this was, because while sometimes there were white guys who should have been on the starting five, a lot of times you could easily see there were five Black players who should have started, or at least four. I thought that this coach’s thinking went along the lines that if he had four Black players and one white on the floor, the four Black players would freeze out the white guy, so then they wouldn’t all play together—even though, of course, this was ridiculous. And if he had five Black guys out there, he figured all the discipline on the team would break and it would just be an undisciplined mess—also ridiculous. And he couldn’t have less than three Black players because it would be so outrageous, given who was on the team and how good different players were. This is how I used to analyze this.

But when I would discuss this with a lot of my Black friends, including ones on the basketball team, they would explain to me very patiently, “Look, man, it’s not just Sid Scott, it’s the alumni and all that kind of shit from the school, people who have more authority around the school, they don’t want an all-Black team out there. So this coach, yeah, he’s a racist dog and all that, but it’s not just him.” And then I would argue, “No it’s him, he’s a racist dog.” And, of course, they were much more right than I was.

My friends and I would go to each other’s houses, stay overnight at each other’s houses, and we’d talk about this kind of stuff all the time—especially the more the civil rights movement was picking up and the more this carried over into all kinds of ways in which people were saying what had been on their minds for a long time but were now expressing much more openly and assertively. One time, when I was a senior in high school, our school got to play in a night football game. Now, we didn’t get to play many night games. They would always be afraid there’d be a riot at the game, because of the “nature of our student body.” I think this was the only night game we ever played. We went on a bus trip to Vallejo, which is maybe 20, 25 miles from Berkeley, and the bus ride took about an hour.

During that time and on the way back after the game I was sitting with some Black friends of mine on the football team, and we got into this whole deep conversation about why is there so much racism in this country, why is there so much prejudice and where does it come from, and can it ever change, and how could it change? This was mainly them talking and me listening. And I remember that very, very deeply—I learned a lot more in that one hour than I learned in hours of classroom time, even from some of the better teachers. Things like that discussion went on all the time, on one level or another, but this bus ride was kind of a concentrated opportunity to get into all this. A lot of times when we were riding to games we’d just talk about bullshit, the way kids do. But sometimes, it would get into heavy things like this, and there was something about this being a special occasion, this night game—we were traveling through the dark, and somehow this lent itself to more serious conversation.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.