Reporter’s Notebook

In the Aftermath of Hurricane Sandy:

How the Other Half Lives in the Jacob Riis Projects

by Li Onesto | December 9, 2012 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

November 4, 2012, six days after Hurricane Sandy hit New York City, we’re walking in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It’s early afternoon and the sun is out and bright, but the wind has a bitter edge and is definitely signaling winter. We’re headed to the Jacob Riis Houses and the dropping temperature reminds me that thousands of people in these government projects just got their power back on, but they still don’t have any heat.

The NYC Revolution Club has been organizing around seven demands, including that the government provide hard-hit areas with emergency housing, shelter, food, safe water, and medicine—all things which at Jacob Riis have been non-existent or totally inadequate. In Harlem, the Rev Club went door to door in the projects, talking to people about the movement for revolution, getting out the demands, exposing how the system is not meeting the needs of the people, and collecting food and water to take to Jacob Riis. People signed a banner that said: “From the people of Harlem to the people of Jacob Riis Projects—We are human beings. We Demand to Be Treated With Respect and Compassion. We Got Your Back!”

The Jacob Riis Houses, built in 1949, were named after a photographer who exposed the squalid living conditions of people on the Lower East Side in the 1880s. Riis’ famous book, How the Other Half Lives, depicted horrendous living conditions and enormous inequalities—which, over 130 years later, still exist in these projects that bear his name. And in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy this situation stands out all the more starkly.

Some 400,000 people live in 334 New York City Housing Authority developments. And many of the brick buildings situated near the waterfront are old and not well maintained. Living conditions here are bad to begin with. So it’s not surprising that those in public housing were affected a lot worse when Sandy hit. And then the second punch came when people were by and large abandoned by the government for days—even as other areas in the city were getting up and running.

Jacob Riis consists of nineteen buildings, between six and 14 stories each, with 1,191 apartment units. About 4,000 people live here. This is the Lower East Side of Manhattan; the buildings are close to the water and when Sandy hit, the tidal surge for a time ringed the buildings like moats, flooding some of the first floors.

Some people, like the elderly, those with diabetes, or others with serious illnesses, were literally trapped when the power went off and the elevators stopped working. For days, there were those who ended up just sitting in their apartments in the dark, some with little food or water. Others had to walk up and down, up to 14 flights of dark stairways hauling water to flush toilets and to try and stay clean. People lined up at open fire hydrants to fill pails and jugs with water.

For several hours, as the sun gets low in the horizon and the temperature drops even further, I talk to people in Jacob Riis about what they experienced in the first week after Hurricane Sandy.

Part 1: Searching for Water

A Black woman named “Gloria” is walking back and forth in front of the building where she lives. A quick strut and the look in her eyes suggest she’s on a mission. But I think she’s also trying to keep warm. She lives in Jacob Riis and describes her struggle in the last several days, just to get water and basic necessities.

“I’m living in this house with my six kids and my two grandkids, the lights came back on but we have no hot water, the water that is coming out of the faucet is brown. We’re basically walking around the Lower East Side trying to find water. I went to one of the park sites where they was giving out water but they didn’t have any more, so they gave me one bottle. They had wipes as well. But they said we had to bring the kids out so that they could see that we have kids, ’cause people are saying they have kids but they don’t really have kids. So they want us to bring babies out in the cold. They gave me two Pampers. They said I have to bring the kids back out. So now I’m just walking around trying to find more water. It’s crazy. We have no power, no nothing. We have been standing on line to get water, canned food. We have to go to the fire hydrants to get water. We have to walk up the stairs, sometimes 14, 15 flights of stairs with buckets of water to wash, to wash dishes. It’s crazy. And you have to bring your kids out in the cold to prove that you have kids to get diapers and wipes.”

Gloria had to wait three hours to get two diapers and a bottle of water.

“And then they were telling me to bring my child here in the cold, so I was like, are you crazy. My baby is like eight months. I’m not going to bring him out here to stand in the cold in a carriage. I need the food but I can’t do that.”

I ask her what the conditions were like in these projects before the storm and she says:

“They do have people that work the grounds but it needs to be better. It’s crazy down here. And right now, you come down here, it’s like you in a different world from being uptown where everything is on, everything is running after the storm. It’s even worse now. We don’t have anything. Like right now I have never experienced this where I have to actually stand before the store with the gate halfway down and they let people in one person at a time to get soda or juice. I mean some places is way worse than this, Staten Island, other places is worse, but this is like a Third World country to me, because I never experienced this. The basic essentials, water, soap. And then if you have a debit card you can’t even use it because there’s nothing working. So you have to have cash, but who has cash like that down here? So it’s crazy. It hurts. It makes me wanna... I get very emotional. I believe they can do better. This is crazy. We have no heat. Why haven’t we gotten any heat or hot water? This is ridiculous. And how long is this gonna be? It’s getting colder, with our babies. And then they talking about us going to shelters. Not everybody can just leave and go to a shelter.”

When I mention that “this is an area where stop-and-frisk is really out of control...” Gloria immediately cuts in, interrupts me and starts talking really fast: “Oh, yeah, stop-and-frisk. My son has been stopped and frisked a thousand times. In our own building. My son coming home and they say do you live here. Yeah, I live here. He said I don’t have ID but I can show you the key to the building and I can take you to my house. They wouldn’t do it. My son is 21. And they stopped him and he’s like I live here. My mother is upstairs, I can call her right now to come downstairs. Another example, one time he was standing in front of the building waiting for us to bring back groceries. They tell him to move. They search him, say you can’t stay. He says, I’m waiting for my mother to come back with the key, she has groceries. They took him to the precinct; they check and say he has warrants. When I get home I went to the precinct, find out he has no warrants. Then they try to say he was disorderly conduct, that’s why they took him.”

I ask her how many times, in one year of high school, her son has been stopped by the police. She pauses for just a couple of seconds, then says, “He has been stopped over 20 times, it had to be,” and goes on to give another example:

“They stopped him one time in front of the building. He was coming home from a party. He was feeling nice, he was going home. He didn’t have the key to the door upstairs. His cell phone went dead so what he did was he put something in the downstairs door to hold it open so he could run across the street to the phone to call us. The police ask him why he holding the door open and he said my parents, we live upstairs but I can’t get in my house, so I’m holding the door so I can at least get in the building. But I’m trying to get ahold of my family. He was telling them all this but then took him in again... This is all so crazy... and now I’m just walking around trying to get water and go back home.”

Part 2: What About the Desperately Poor?

The Revolution article “On Hurricane Sandy—What Is the Problem? What Is the Solution? And What We Need to Do Now!” poses the question, “Did those with real power in this society—the capitalist-imperialists—make sure that everybody would be adequately provided with necessities in the face of this disaster?” And then answers, NO:

“They left whole areas where the basic people at the bottom of society live without water, heat, electricity or food—and then they clamped curfews on them. And they also meted out outrageous, uncaring and downright dangerous treatment to people in more middle-class areas that were hit as well.

“Did they even make sure that people—including the desperately poor in this society whose food typically runs out by the end of the month—would be able to eat when Sandy hit?” (Revolution #284, November 4, 2012)

The fact that the system DID NOT do this is stark here at Jacob Riis—and underscores how profoundly different a revolutionary, socialist society would handle such a situation. Raymond Lotta points out, “In a crisis like Hurricane Sandy, the socialist state would allocate needed resources, like food, temporary shelter, building materials, equipment, to where they would be needed most. This will not have to go through the patchwork and competing channels of private ownership and control that exist in capitalist society.... emergency priorities would be established—for instance in identifying the most vulnerable sectors of the population, helping the most devastated communities or areas of historic oppression...” (“Why a Natural Disaster Became a Social Disaster, and Why It Doesn’t Have To Be That Way,” Revolution #284, November 4, 2012)

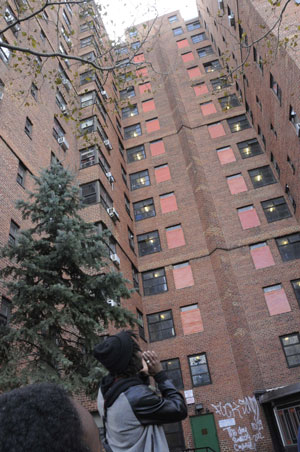

Jacob Riis Projects

Photo: Special to Revolution

One resident from Jacob Riis pointed out that because Sandy hit at the end of the month, many people hadn’t gotten or been able to cash their disability, social security, or other end-of-the-month checks they depend on and so didn’t have much food, making a bad situation even worse. Another person said things were bad enough before the storm, that there’s always been big inequalities between here and “uptown,” but now all this stands out even more.

“Trina,” a 28-year-old Black attorney who lives in Harlem, just met the Revolution Club and joined them in collecting food, water, and clothing to bring to people in Jacob Riis. She says, “It’s not surprising, the idea that the resources were gotten out to the affluent areas first. The media told us that the power was turned on down here but there are buildings here without basic necessities.... The fact is that it is still necessary a week later for community members to be donating to each other as opposed to what the government should be doing.”

I tell Trina about a letter posted at revcom.us that describes how a shelter treated poor people who were evacuated, not with compassion, but like they were criminals, and she says:

“The thing that’s interesting is it’s not just the storm victims that are being treated that way. That’s the way people are treated in shelters generally. I have some experience with this just working with some of my clients. Many of them are residents of these shelters and I have had cases that involve shelters. I had a case where a client felt he was being targeted by shelter security and the NYPD. Many people in shelters are treated like criminals. He preferred to be on the streets than in the shelters because to him it’s the same as being in jail and it’s unfair because he’s only there because he can’t afford to be anywhere else. People know that the shelters are not comfortable places to be. And not just uncomfortable but you’re treated poorly. They know what it’s like and they would rather chance being re-incarcerated than having to live at a shelter. That happens all the time. . . . So it’s not surprising that storm victims are treated poorly in the shelter system. People that are typically in the shelter system are treated poorly. And I even hate that term, ‘treat them like criminals’ because we criminalize normal people. We criminalize everyday people. ‘Treat them like criminals.’ What the hell does that really mean? It’s terrible.”

“Something Wasn’t Quite Right”

Soon after this conversation, someone tells me that “Jackie” up on the 10th floor wants to tell Revolution about her experience in a shelter after Hurricane Sandy. The elevators still aren’t working and as we start the long walk up, I imagine what it was like to haul water up all these stairs, with no lights, for days. Jackie, a Black woman in her late 40s, is waiting in the hallway, eager to talk and she’s already way into her story before I even get my recorder on. When I get her to back up and start again she says, “It was the worst... I should have stayed home... and I’m going to chat about it!”

She lives in Jacob Riis with her 13-year-old, 9-year-old and grandson, who is three. She says living here has been “hell... even before the storm,” with leaking ceilings when it rains and other problems. She recently found out she has diabetes and her children suffer from asthma. Jackie says that at first she didn’t think the storm was going to be that bad so she didn’t evacuate. Later, when she got scared for her kids, she decided to go to one of the shelters. But soon after they got settled, Jackie says, “something wasn’t quite right.” They were given meals but hardly any water—so the only water she had for a while was what she had managed to bring from home. Increasingly, she felt the whole situation wasn’t safe for herself and her kids.

“I met some ladies from my building there. We were taking turns watching out, because men would come up to the floors and walk through. And we wasn’t safe, we had our kids. So we would take turns with the flashlight and we would stay up. I had fell asleep the night before and I was up that night and like I said, we was taking turns.

“We started complaining, why we not getting any help, why we not getting any water. In a few hours they came up and gave us water, but it was like—one water for you, one water for you. One water for me and all my kids.”

Given her diabetic condition and not having any water, Jackie started feeling really bad with a terrible headache and went down to the medical station. Her blood sugar tested really high and when she asked the doctor what she should do he told her to “drink a lot of water”—which, as Jackie pointed out, “Was really crazy—because they weren’t giving anybody any water!”

Finally, Jackie decided to go back home. “Even though it was dark here, even though we didn’t have no hot water, no heat, no nothing, just a stove to light with matches to try and get some heat. We still came home, even there was no elevator. With asthmatic kids, we climbed those stairs, with the shopping cart.”

Jackie has already been talking for a good 30 minutes, but she wants me to know how bad it was, not just for her and her kids, but for others who were also at the shelter. So all of a sudden, she grabs my hand and leads me to the stairwell. She takes me down two flights and introduces me to her friend Jeena. “Talk to her,” Jackie says, “She’ll really tell you how bad it was.”

To be continued

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.