Notes on promoting the new synthesis at the Foro Social Mundial Binacional Tijuana

August 3, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

At Friendship Park in Tijuana, visitors to the beach as well as forum participants carefully studied captions on the combination Stolen Lives and Ayotzinapa 43 posters. Above, a forum participant from the Cucupá tribe’s struggle for traditional fishing rights.

At Friendship Park in Tijuana, visitors to the beach as well as forum participants carefully studied captions on the combination Stolen Lives and Ayotzinapa 43 posters. Above, a forum participant from the Cucupá tribe’s struggle for traditional fishing rights.

Holding up the combination poster at the border wall, which is painted with slogans and other protest artwork all along its length. Above, graffiti reads: A la mierda las fronteras (Fuck borders) and Esto es una gran herida para la humanidad (This is an immense wound for humanity).

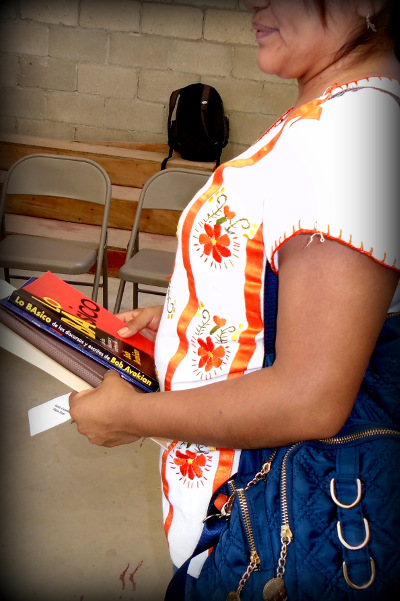

Getting into Lo BAsico at Friendship Park. In the background, the U.S. flag painted upside down on the border fence.

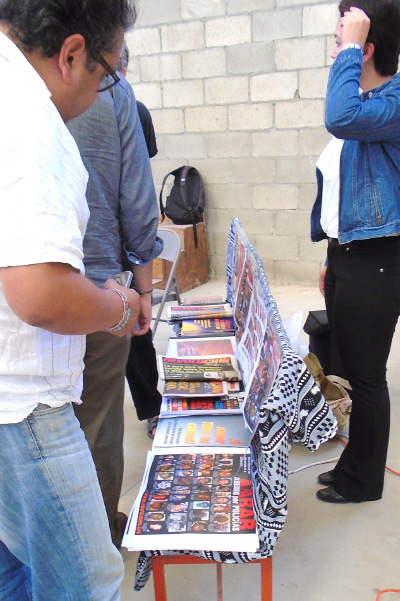

Conference staff helped set up and watch over a literature table next to the queue for tacos.

We left before sunrise from LA, and crossed the border into Mexico several hours later. We were headed to Friendship Park for the morning cultural event of the Foro Social Mundial Binacional Tijuana (World Social Forum (WSF) Bi-national Tijuana). Friendship Park sits in the actual shadow of the border, marked by the 20-ft.-high double fence that stretches eastward for 1,000 miles and more, symbolizing and enforcing U.S. imperialism’s relationship with Mexico and the rest of the world. The fence is covered by bright paintings and slogans that denounce the suffering it causes and celebrate the international friendship of people in the face of that. Right here, every night, people separated by the border gather to call out to loved ones on “el otro lado,” the other side.

Tijuana is a city of over 1.4 million, on Mexico’s west coast, defined by its proximity to the U.S. Border Patrol agents from ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement) have shot across the border into the colonias (neighborhoods), killing children with impunity. The U.S. military and its many naval bases in San Diego County have, for decades, used Tijuana as its whorehouse. Some of the earliest maquiladoras (factories in Mexico run by foreign companies) were set up here with slave-long hours, starvation wages, and lack of safety and environmental protections. The sex traffickers, maquiladoras, smugglers, and drug cartels all exploit the huge population of migrants from the Mexican interior and Central America who are stuck in limbo in Tijuana. Tijuana is also home to growing professional and middle classes, many human rights organizations, and several universities.

The one-day Foro in Tijuana was part of a simultaneous multicity four-day conference. In Philadelphia, San Jose, Houston, and Jackson, Mississippi, gatherings organized by the US Social Forum would be linked by video conference with Tijuana and Montreal. Social movement activists from across North America were gathering in response to a call issued at the World Social Forum’s 2015 Tunis Conference on Climate, Water and Earth to make plans for a “world-wide week of coordinated actions against capitalism October 17-25, 2015.” (See “Report on promoting Bob Avakian’s new synthesis of communism at the Tunis World Social Forum,” May 4, 2015.)

A couple days earlier, hearing that this Foro Social Mundial would be just a few hours away, volunteers from Revolution Books/Libros Revolucíon Los Angeles had made hasty preparations to cross the international border and register for the conference. We were eager to get key works of BA’s new synthesis in Spanish into LOTS of hands—Revolución newspapers and eSubs, El comuismo; El comienza de una nueva etapa; Un manifiesto del PCR, EU (Communism: The Beginning of a New Stage; A Manifesto from the RCP, USA);and Lo BAsico (BAsics);the Constitution para la nueva republica socialista en America del Norte (Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America); BA’s ¡A romper TODAS las cadenas! (Break ALL the Chains!);the polemic “¿Comunismo or Nacionalismo?” (by the Revolutionary Communist Organization in Mexico, OCR); and the DVD of BA’s talk Revolution with a Spanish audio. Even though only one of the two of us was fluent in Spanish, we were confident that the posters, newspapers, and books themselves would help us project that this was about making an actual revolution; and that in turn would draw people forward to help get the books out at the conference and across Mexico.

On the drive to the border, we talked over our orientation and plans. What would we find among activists taking part in the current political upheaval in Mexico? There had been defiant and widespread resistance to state-sponsored murder on both sides of the border, including the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students, attacks against people’s community defense forces in Mexico’s southern states, and other challenges among other outrages. Was this being sustained? Had it fallen off or gotten co-opted? What was the Mexican people’s sense of the legitimacy of their government? Did they have revolution on their minds? Would there be an atmosphere of snark, or anti-communism? Had people heard of BA and the new synthesis?

From the minute we arrived, we were greeted warmly, including by one of the main conference organizers. We started right away, getting out the Stolen Lives poster and Revolucíon (the issue with “Murder and Brutality by Police is Unjust, Immoral, and Illegitimate” on the front cover and “Take Patriarchy by Storm” on the back cover). The first person we met was a Puerto Rican US Social Forum activist who had seen the Stolen Lives poster as she was protesting “We Can’t Breathe” in the streets of New York last fall. She and an activist from Tijuana’s LGBT movement helped get up the Stolen Lives posters, and to make them extra secure from the stiff ocean breeze. Seeing the Stolen Lives poster alongside a poster showing the faces of the 43 disappeared Ayotzinapa students, someone who said he was one of the organizers objected. He said that we were welcome to talk about “our issue,” but that Ayotzinapa was a Mexican issue. Several people (the gay activist, joined by some human right activists) took this on, saying, in effect, “the same imperialism hurts both countries. And this shows that people here and there are standing up saying this must STOP now.” In the face of their animated response, he just walked away, and we never again had any challenge to what we were doing at the Foro.

We spread out literature of BA’s new synthesis on a bright-patterned cloth on the ground close to the stage. A steady stream of people came up to see the poster and get books. Not only were people friendly and interested, most were enthusiastic, and some were ecstatic to encounter the literature representing a movement for actual revolution. Soon, all across the plaza people were reading the newspaper, as various musicians sang about injustice, love, and resistance.

There was a lot of interest in the Stolen Lives poster. A few people recognized the poster from news coverage of Ferguson, Baltimore, and other protests, and were eager to get one for themselves and more for their friends. Many more, seeing it for the first time, expressed deep feelings for the people of Ferguson and Baltimore, and said how moved they had been by their defiant resistance, comparing that to their resistance to widespread government “disappearances” of activists, including the Ayotzinapa students. They were curious about what we had to say about what it would take to stop all of this, and how that related to BA’s new synthesis. Others were more generally curious about our political trend, and what this “beginning of a new stage of communism” was all about.

Taking a look at Lo BAsico (left) and the Manifesto (right).

At the entrance to the morning event, the World Social Forum banner, to the left a banner from the Otomí people of Xochicuautla resisting a highway which will destroy their lands, and below that, the Stolen Lives/Ayotzinapa combination poster.

Among the most eager to get EVERYTHING at the book table were young indigenous farm workers fresh from the major strike against international agribusiness, 200 miles to the south in San Quintin. (See “‘We Are Workers, Not Slaves!’ Farmworkers in Baja California Stand Up!”). They wanted to know about the Party, and were particularly insistent on getting the Constitution para la nueva republica socialista en America del Norte. (There was so much interest that we sold out within minutes, with people still standing in line for it, while we looked in vain for more copies.) Although most from San Quintin who got books were young men, there was a significant contingent of young women, some of whom had made statements during the morning’s presentations. As one of us recalled later, “Their eyes shone with focused and serious attention” as they listened to our brief rap about communism, scooped up books and the Revolution DVD to take back to their communities.

A group of young lesbians greeted the newspaper with glee. They loved the Stop Patriarchy poster on the back of the newspaper (“Women are not bitches, hos, incubators, punching bags, sex objects or breeders, They are Full Human Beings”).They marveled that a communist newspaper would feature something like that. We said that is something new—it represents the outlook of BA’s new synthesis of the best of the first attempts by the oppressed at creating a new society, what has been learned from their shortcomings and mistakes, as well as recent developments in the world. Everyone from that cohort got a copy of the newspaper and a Stop Patriarchy poster, and some also got copies of Lo BAsico, the Manifiesto, and BA’s compendium on the emancipation of women and communist revolution, ¡A romper TODAS las cadenas! We learned that they were some of the organizers of the Tijuana “Marcha de las Putas” (Slut Walk) that we had heard about on social media. They came to the conference, in part, to find others who have an in-your-face stance, and to find others who want to go up in the face of everything that preaches complacency in the face of outrage and suffering. They invited the bookstore and/or Stop Patriarchy to participate in their July film festival in Tijuana.

Some of the activists had participated in other World or US Social Forums, but for most it was their first time at this kind of event. In addition to those already mentioned, we met radical-minded activists who have formed small cohorts all over Mexico; members of indigenous groups including Yaqui, Guarijío, Triqui, Otomí, Cucupá, and Kumiai peoples fighting for water and land use rights; professional human rights advocates; activists with migrants’ and women’s shelters; and professors, students, and activists fighting fracking and on other environmental fronts.

In this environment, our literature and book display became the magnet for those with serious questions, including about the possibility of revolution, especially for those who had come to the conference with, or representing, a cohort or organization that was fighting the power and looking for a way forward. In many cases, they would share the expense of a whole set of the literature, with one person getting the Manifiesto, another the OCR polemic, or Lo BAsico, and so on. The most frequently asked question was where else could they find this literature? We pointed to the page in the newspaper that said “revcom.us.” Many people circled the spot to find it later.

By noon, well over half of the crowd had gotten the current issue of Revolucíon, and there were over two dozen new eSubs. Most of the books we brought were already in people’s hands and we would have only a handful of books left for the afternoon’s workshops, where activists from the morning event would be joined by another several dozen students and a similar number of professionals who work with human rights groups and NGOs. Before the workshops began, a couple of the conference’s student volunteers helped us find a long bench for our display, and put it right in the workshop venue, inches away from where people would queue up for lunch. Then, after themselves signing up for eSubs, the new volunteers helped call people over to the book “table,” and distributed a stack of Lo BAsico palm cards.

The workshops were based on WSF’s key topics: Migration; Gender and Diversity; Labor and Wages; Water and Soil; and Macro-projects and Environment, with 90 minutes to discuss the topic and come up with recommendations, including plans for the week of actions in the fall. This format gave a platform to those working within various social service agencies, who mainly described the abuses they were fighting, outlined the program of their group or agency, and left many people frustrated and disappointed at those limitations.

At the workshop on Gender and Diversity, almost everyone focused on the rising tide of violence against LGBT, especially transgender people, as well as against women. Some questioned whether there really was any solution to social issues like these, and argued that the only option for LGBT people was to rely on themselves and allies to create what amount to “safe spaces.” Others argued the flip side, calling mainly for better documentation of abuses that could make the case to political leaders and get better laws enacted, that any high-visibility, bold actions would alienate political allies. When it was one comrade’s “turn” to speak, she gave props to the different ways people were fighting these attacks, but challenged people to look more deeply at WHERE this all comes from—patriarchal relations that are enmeshed in and essential to the functioning of capitalism-imperialism. If they did that, they would come to see that the only way to really STOP this abuse and suffering, the only way to get rid of relations of masters and slaves, is by making a revolution that demolishes this system and its enforcers, and creates whole different economic and social relations. Without THAT kind of revolution, even the most determined fighters will be waging the same battles over and over. She gave Ferguson and Baltimore as examples of the possibility of creating new conditions through struggle, that “fight the power, and transform, the people for revolution” is a far more “real” strategy. One of the conference student volunteers took a stab at translating all of this, but the workshop convener brushed her aside and proceeded to characterize what we had said as offering solidarity and inspiration from north of the border(!) During this bad “translation,” several of the lesbian activists moved their new Manifiestos and Lo BAsicos to where they could be seen by everyone at the table. What did THAT represent?

The discussion, though, got steered back to going around the table for recommendations about better legislation and safe spaces, until an indigenous woman stood, and with great emotion asked people how they could get so lost, talking on and on about law and government. “Don’t you know the government is not your friend? Look at the history of my people. Look at all of history. Government is the friend of the masters, not the slaves. They think nothing of killing.” She said that people needed to act like they did in Ferguson, that the proposals for more “practical” actions were a “deadly distraction” from what needs to be done. “I’m not here for that! I want to find others who feel the same way, and organize those networks.” With that, she took her children and walked out. The convener went back to prodding people for recommendations to take to the plenary, but found few still interested in participating. (We didn’t move quickly enough at that moment to catch up with the indigenous woman, and never saw her again, but did get some literature into the hands of someone from each tribe.)

Perhaps the most interesting question raised at the Migration workshop was, “What about the right to NOT migrate?” Unfortunately, the question and what that implied about the system was never really joined. The discussion was structured for each person at the table to talk, in turn, about their own issue or connection with migrant issues, and their proposed solution. Not only did this narrow the scope of understanding migrations that are sweeping the planet, it had the effect of promoting the outlook that what is possible is what is already being done—with the addition of more voices, or fervor, or funds. Even people whose intentions were better ended up complaining about stuff like Tijuana having to handle deportees from all over Mexico. When it was our turn to speak, we tried to raise sights to the source of this massive disintegration and uprooting, not only in Mexico but all over the world, and concluded by saying, in effect, “It is imperialism, especially U.S. imperialism, and it has to go! We need revolution. I live in the U.S. but I’m not an American, I’m an internationalist.” Several people expressed agreement in different ways and for different reasons with that. A young woman who works with an agency helping deportees responded later with a big hug, and expressed gratitude for words that expressed how she felt, saying, “‘I’m an internationalist!’ I’m going to remember that phrase.” But a moment later, discussion sank back to individuals’ issues, and the workshop ground on toward making “practical” recommendations to the plenary.

The final plenary session video-conferenced workshop recommendations to participants in the other cities. Most people left quickly, even before that was finished. But several lingered to ask us to keep in touch, or if we would come and talk to their group after they had studied and discussed the books on the new synthesis. Two people tracked us down specifically to get the OCR polemic. When we asked one of them, a young indigenous woman who was already holding a Manifiesto and a Lo Basico, why she wanted the polemic, she answered obliquely, before she hurried away, “I think I will like it.”

Everything we had brought with us was now in the hands of people from throughout Baja California or other Mexican states, including Chihuahua, Sonora, Sinaloa, and the Federal District (Mexico City).We had arrived with 35 copies of the OCR polemic, 25 Manifiestos, 15+ each of Lo BAsico and the Constitución, 30 ¡A romper TODAS las cadenas!, 12 copies of “¿Pero como sabemos quien esta dicienco la verdad sobre el comunismo?” by Raymond Lotta, five DVDs of BA’s Revolution talk with a Spanish audio, and could have gotten out nearly twice as much. Thirty-one people signed up for revcom.us eSubs, and bought or made donations for 88 Revolucion newspapers (various issues).

The whole day was a real emotional high for us, seeing people’s excitement and obvious hunger for revolutionary theory, and giving us a sharp reminder of what a rare and valuable thing we have in the BA, his new synthesis and his leadership. Crossing back into the U.S. was depressing, but uneventful. We talked about where to go from here in connecting up people with revcom.us, including the 17 who had volunteered to translate, and kicked around how we could raise funds both to repay the bookstore and for the literature to get out internationally on a grand scale.

That morning we had decided to lower the price of the books, given that the minimum daily wage in Mexico is 70 pesos (less than $5, or half of the price of Lo BAsico), which likely made it possible for many of the more basic masses to get the books. And we also consistently asked for donations to make that possible. Several Mexican professionals doubled the price they paid, to help others get the books. Now, heading home, we made plans for a fundraising house party to let friends back home hear what we had learned about the hunger for revolutionary theory, how precious revcom.us is to people all over the world, and what their commitment to sustaining revcom.us can mean.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.