Revolution Interview with B. Lynn Ingram

What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us about Tomorrow

October 5, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Revolution Interview

A special feature of Revolution to acquaint our readers with the views of

significant figures in art, theater, music and literature, science, sports and politics. The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our paper.

B. Lynn Ingram is Professor of Geography and Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the co-author, with Frances Malamud-Roam, of The West without Water: What Past Floods, Droughts, and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us about Tomorrow. ScientificAmerican magazine says of the book: “Part detective story, part call to action, this book offers vital advice of how to fix the West’s looming water crisis.” Orpheus Reed recently had the opportunity to interview Dr. Ingram for Revolution.

Revolution: Let’s just jump right into it. There’s this situation in California with the extreme drought that has been going on for several years and then these terrible wildfires that have been happening this year. Could you just start with giving a basic picture of the situation as it stands right now?

B. Lynn Ingram: Well, we’re in the fourth year of a severe drought, but if you look a little further back it’s actually since 2002; 13 years have been below average in terms of precipitation and run-off. So the thing is the soils have been drying, the vegetation has been drying—and so in terms of leading to larger and more frequent wildfires, there’s been a trend that actually started back in the ’80s, seeing more frequent wildfires that researchers attributed to global warming, since we’ve been seeing a lot of warming especially since the ’80s. So that’s causing drying of soils, drying of vegetation—so there’s a definite correlation between those two.

Currently we’re like 60 percent of long-term average precipitation now, so it’s pretty severe. And I think the last four years are the four driest years we’ve seen in a thousand years, if you look in four-year increments. But like I say, since 2002, 11 of the last 13 years have been below average. In the Southwest I think they’ve been in drought since 2000, 1999 or 2000. It’s almost that bad in California.

Revolution: How would you characterize this crisis, and could you talk a little about some of the impacts of the drought on the people living in California, on ecosystems there, wildlife, etc.?

B. Lynn Ingram: Right. In terms of the wildlife, it’s definitely been impacting some of the aquatic ecosystems the most because stream flows, river flows, are down. On top of that we’ve been withdrawing a greater fraction of freshwater during the drought. So salmon are really suffering, and the Delta smelt, which is endangered and endemic to just the Delta, are almost gone. They’re literally counting the number of fish left and there are very few, and that’s kind of an indicator species of the whole aquatic ecosystem in the Delta and San Francisco Bay as well. So I think as more freshwater is making it to the Delta and San Francisco Bay, the salinities have been going up and it’s been impacting the aquatic ecosystems there quite a bit.

The salmon, these fish that migrate through the Bay and Delta, are really suffering because of the ongoing drought. That started a few decades ago, but it’s taken a plunge in the last decade and then the last four years. There’s more disease with the forests, infestations of bark beetle or other insects. When the trees are weakened by drought, they’re not able to fight off disease infestations as easily, so they’re susceptible to these diseases. As the trees die they dry up even further, and that further fuels the wildfires. So some of that is, I think, the temperatures of the wildfires have gone up and there are more severe wildfires ’cause the trees have been weakened and dried up more, so there’s more fuel for fires,

Normally the trade winds in the tropical Pacific Ocean blow towards the west from a region of higher pressure in the eastern Pacific to a region of lower pressure in the western Pacific. These winds enhance upwelling (the rising of cold water from the deep ocean towards the surface) in the eastern Pacific off the coast of South America. Therefore, sea surface temperatures, as seen on the figure above, are cool off the coast of South America and significantly warmer in the western Pacific.

Every few years, this pressure pattern breaks down, resulting in higher pressure in the western Pacific and lower pressure in the eastern Pacific. This causes the winds to slow or even blow towards the east instead of towards the west. This wind reversal brings the warmer water from the western Pacific towards South America. This warming of the ocean is El Niño.

Source: NOAA - National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Revolution: I wonder if you could speak to the causes of this drought and how you see that—what is understood and what is maybe not so clear at this point?

B. Lynn Ingram: Well, if you look at the longer-term history, it’s true we have cycles of weather, fire, and climate that have to do with conditions over the Pacific Ocean. So there’s different time scales of these cycles, like there’s the Pacific Decadal Oscillation. So those are every few decades, you get shifts in the north Pacific temperatures that affect precipitation. Then of course the El Niño cycles are like every two to seven years. But the concern is that superimposed on the natural cycles, we’ve got a warming trend that has caused a shift in the storm track further north, so fewer storms are actually reaching California and the Southwest every year. And we only get six to seven big storms in a normal season. So if we start falling short a few storms, then we consider that a drought.

Because we’ve developed our water, it’s a very fine balance for us ’cause there’s so many people living here. Part of it is the demand. We’ve got 39 million [people] and that’s projected to increase a lot. So we’ve developed all of our rivers, we have dams everywhere, we’re pumping groundwater already and depleting our groundwater—so any decrease you have, even if it’s a couple storms a year, we’re going to feel it a lot. That seems to be a trend that researchers are looking at—that this started a couple decades ago, a gradual trend of drying in this region. So instead of assuming all this is just a natural cycle, I think we have to really prepare for a drier future. This could be a longer-term trend with warming, and really start doing the things that would help us recycle and reuse greywater and things like rainwater harvesting, and treating wastewater so we’re reusing it. Some places are doing this in Southern California, I think in Orange County—I think they’re treating their wastewater and putting it back in the ground, so instead of it just running off, they can reuse that after a certain amount of time.

But on a statewide level, it seems we should be doing more with water conservation. I mean, we’re starting to do it, but in terms of recycling and reusing water, I don’t see it happening widespread here.

Revolution: I read your book The West without Water. I thought it was really what the back cover says: part detective story and part call to action. The subtitle of the book is “What Past Floods, Droughts and Other Climatic Clues Tell Us about Tomorrow.” That’s obviously a big topic and there’s a lot involved there, but I wonder if you could give a basic overview of what these clues do tell us.

B. Lynn Ingram: One thing is that there were extended droughts in the past, like during the Medieval Warm Period and the middle Holocene 5 to 6,000 years ago. There were periods when we had drought that lasted decades to over a century. And it seems like even droughts lasting a couple of decades occur pretty regularly, like one or two decade [droughts] we might see every 1 to 200 years. Even without global warming we have to prepare to get through these periods of perhaps longer than we’d seen since we’re keeping records, like since the late 1800s. We really have to realize that the climate is capable of longer droughts naturally. So that was one lesson.

And another is that it seems that these extended dry periods, the longer ones like during the Medieval Period and then the mid-Holocene, those occurred when it was relatively warmer. So in the Medieval Warm Period, the Northern Hemisphere was warmer. And then during the middle Holocene, it wasn’t warmer due from CO2—there’s debate about why it was warmer, but there are a lot of different records showing it was warmer. So in general, that trend of seeing the storm track move further north and getting less precipitation in California and the Southwest has happened in the past during warm times. So with global warming, we can expect it to be drier. I mean, the models say that, but it’s always nice to know that it actually has happened before. It kind of confirms the models.

Just on the other end of it, we can also expect these big floods that we write about [in the book], so we can’t ignore the other side of it, which is even if it gets warmer, periodically because of atmospheric river storms from the tropics, there can be these big floods. I think people are trying to get an awareness, especially the U.S. Geological Survey, of the fact that we are susceptible to big floods in this state also. Like in the Central Valley, places that were really under water, we should be careful of where we expand our cities because we’re expanding into flood plains that could potentially be under water if we ever have a big flood again.

Revolution: Could you briefly describe what you mean by atmospheric river, and also how often do those happen compared to drought?

B. Lynn Ingram: So the atmospheric rivers are... smaller ones are pretty common—literally, we have a few every year, but they’re smaller so it’s not like they cause the massive flooding that we saw in like 1861-62, that historic flood. That was a series of atmospheric river storms that lasted like 43 days. That’s less common, but in looking at past paleoclimate records, we see that even those were every 1 to 200 years. So it’s more on the big earthquake kind of time scale, where you should plan for it, but it’s not like it’s going to happen all that frequently.

But these atmospheric rivers, it seems like every year the heat is building up at the tropics and you have a lot of evaporation, so a lot of water vapor at the tropics—and it seems to be the way the Earth releases that heat to redistribute the energy globally, it happens along these narrow bands that radiate out from the tropics and head to the mid-latitudes. So in the Pacific it happens and in the other oceans as well—and so it’s a normal thing, but it was discovered about a decade ago just with satellite imaging. So now we know that that’s what’s happening. It’s a normal phenomenon, but they think as the Earth warms it could become larger because with increased heat, you’re going to have more evaporation at the tropics and that there could be more atmospheric river storms. So it is something that’s gonna keep happening, even if it’s drier you’re still going to periodically have these storms and they may get a little larger, so something to be aware of.

I think you’re right that the droughts are a bigger long-term problem, but these are something we should also be aware of, in terms of where is all the expansion happening. Like if it’s in the Central Valley with cities, that’s not a good thing and people should be prepared for evacuation and things like that.

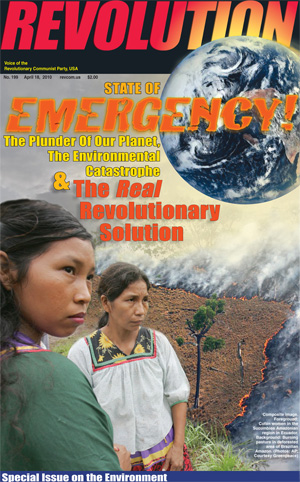

This Revolution special issue focuses on the environmental emergency that now faces humanity and Earth’s ecosystems. In this issue we show:

- the dimensions of the emergency...

- the source of its causes in the capitalist system, and the impossibility of that system solving this crisis...

- a way out and way forward for humanity—a revolutionary society in which we could actually live as custodians of nature, rather than as its plunderers.

Read online....

Also available in brochure format (downloadable PDF)

Revolution: So what you’re saying is, with global warming you can have more intense droughts but you can also have, maybe less frequently but still periodically, really intensive rainstorms and flooding as well.

B. Lynn Ingram: Right, exactly. And also with global warming, because the snowpack, it’s going to be warmer in the mountains in the Sierras, that in the wintertime you’ll have more precipitation falling as rain than snow. And so that will run off immediately, and they’re also warning of more frequent flooding during the wintertime on a more regular basis. Because normally you have the snow that slowly melts in late spring and summer, so the summers are going to get drier because you’ll have less snowmelt. And the winters will have more runoff and potentially flooding.

Revolution: I was fascinated by some of the methods you actually use to discover these clues about past climate and some of the ways you go at that and what you can learn from some of these things. I want to ask you about that in a minute, but first, there’s a couple things I’m dying to find out about. First, I’ve heard a lot of talk about an El Niño developing this year. There are different things said about that—it might help the drought in the Southwest, but then other people have said it won’t end the drought by any means. So I wondered if you might talk about that.

B. Lynn Ingram: OK. In California where we have one to two years of water deficit, even if we had normal or greater than normal precipitation, it’s not likely we will alleviate [the drought] in just a single year. On top of that, in the Central Valley, the groundwaters have been pumped so the water table has been dropping and subsidence of the land surface from all this. That’s something I don’t know would take how long, if you really tried to replenish. It’s like the water in the bank that is just going away because we don’t have any regulation on groundwaters really. I think they’re talking about it for the future, but it’s not happening yet.

With the El Niño, there’s a higher probability that Southern California and the Southwest will be wetter, but right now they’re not really sure where it will turn drier, ’cause in Northern California it can go either way. An El Niño can be a normal year or even drier as you head to Northern California or further north. So where that boundary is fluctuates with different El Niños. I think most El Niños it’s wetter in Northern California, but there’s been a couple when it’s been drier, so there’s some probability, like maybe a 33 percent chance, it could be drier, otherwise it will be wetter! Which is too bad ’cause we really need it in Northern California—that’s the wetter part of the state and there are a lot of reservoirs up here, so we’re hoping that it’s wetter in Northern Cal.

Revolution: I wrote a piece in Revolution on this California drought, and in looking into it, one thing that really struck me was how the whole development of California—the development of the major cities, this whole explosion of people, the building of California into this whole agricultural empire—how this took place on the basis of a completely unsustainable approach, especially in regard to this use of water and the whole climate history that you’ve spoken of. I wonder if you could just go into your view on that.

B. Lynn Ingram: I think it started in the early 1900s and that was a relatively wet couple of decades. So they didn’t have a long-term history or many records of precipitation. There wasn’t the knowledge that we have these big fluctuations, and so I think there was an assumption it would continue. And then we went into the Dust Bowl drought, and it seemed like then our population started to go up and agriculture started to develop in the Central Valley. And so that’s when they started building a lot of dams and aqueducts and pumping groundwater—the groundwater pumps were invented about that time. In the 1930s they started pumping groundwater to make up for the shortfalls with the Dust Bowl drought of 1928-34. Then I think it just went from there that the population kept growing as we developed and started bringing more water to the cities from the Sierra Nevada. The population grew and then as the population grew you kept needing more water, so it turned into a positive feedback loop or spiral, increasing agriculture and population and you kept having to build more dams and harness more water, pump more water.

It feels like we’re still on this—the population’s still going up even though we’ve pretty much maxed out all our available surface water and even the groundwater; we’re depleting, the water in the bank, so to speak. So it’s amazing to me that it’s still happening even though the people who know about water, who should be informing... I don’t know how they’re regulating or deciding whether to have these big developments, these housing developments going up everywhere, but it’s definitely continuing even though there’s not the water resources to support it.

Revolution: So given this whole picture of the drought and how this is affecting things, I want to ask: What do you think could be done, in terms of the use of water, the protection of ecosystems, but also meeting people’s basic needs—what could and should be done to deal with this crisis? If you had a situation where you could proceed really from what’s needed, what would we do to deal with this crisis?

B. Lynn Ingram: I think we could, and we talk about it in the book, we can look at Australia as a model. They had a decade-long drought that was really severe. So they started doing a lot of things people are talking about, like recycling wastewater and requiring everyone to have water-efficient appliances, no lawns, severely regulating things more than I see happening here—where you really have to cut back on water use of the different sectors, and then start recycling water. I talked to an Australian who said he had a rainwater harvest system on his roof, and he said everybody has that now. I don’t know anyone here with one, and I heard you need a special permit for one—they make it hard to even do it here.

It just seems like we know a more collective plan with having things that are in place that will really start to recycle and reuse water and agriculture—I think it’s starting to, but even more than they’re doing now. And also have the price of water reflecting its actual cost to the environment and its scarcity. That’s clearly not in there where we’re decimating the natural environment by taking away this water, and the cost of water is so low, there’s no incentive for some people to really conserve water.

Revolution: One last question. I wanted to ask about the clues about past climate—the methods that you use to learn about these past climates and what has happened in the past. Could you give some examples that stand out to give our readers a sense of how that’s done?

B. Lynn Ingram: OK, so we have to look at these natural archives of climate, before humans were keeping records of climate. So we have to look for clues and proxy records that are contained in natural archives. And those range from things like tree rings, ’cause tree growth—you have to pick your type of tree and locations and so on—but you can look at the width of the annual growth bands that reflect the environmental conditions, like precipitation and temperature. That’s one common method. And then other methods involve looking at the size of lakes, like in the Sierra Nevada or in the desert, the Great Basin, researchers can look at, because these lakes get smaller during times of drought and larger when it’s wetter.

And also at sediments that are accumulating in either the coastal ocean or in lakes, in estuaries like San Francisco Bay. These sediments contain fossils, and you can look at the chemistry of the fossil shells or the chemistry of the sediments themselves that reflect things like water temperature, the salinity of the water, that in turn reflects how wet or dry it was.

That’s the whole detective part of the story—so we have to look at, and come up with as many ways of analyzing, these archives if we can, by looking at these chemical or biological clues. Like what organisms lived there or the pollen will reflect the type of vegetation growing in an area that in turn reflects the climate ’cause that determines the vegetation.

So there are a lot of different angles we can take to really look at how climate has changed in the past and how is that reflected in these natural archives that we find. And also the archaeological records are important so we can see how these things affected humans, for the big medieval drought caused people to abandon certain locations and mass migration and starvation, so you can see clues and relate those to the environmental changes as well.

Revolution: Well, it’s really a fascinating story and I’d love to ask you more questions, but I know you have to go, so thanks so much for the interview. Really enjoyed it!

B. Lynn Ingram: Sure! Thank you.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.