A Glimpse of the Meatpacking Horror Show Made Worse by COVID-19

| revcom.us

Editors’ Note: Trump’s recent executive order mandating meat and poultry processing plants as “critical infrastructure” that needs to “continue operations”—even as the COVID-19 pandemic rips through the workforce—is shining a light on this industry and its super-exploitative nature. The Trump/Pence regime is viciously racist and anti-immigrant and, therefore, hostile to the masses who work in these industries, which now is more than 80% nonwhite, with large numbers of immigrants.

In reading this, it reminds us of Bob Avakian's point that despite “all the great and grand talk from proponents and apologists of the capitalist system about the rights of individuals… yet this system functions, and can only function, by—quite literally and with no exaggeration or hyperbole—grinding into the dirt the lives of millions and even billions of individuals, including hundreds of millions of children, people whose individuality, whose individual aspirations, are counted as nothing in the actual operation of this system.” (From RUMINATIONS AND WRANGLINGS, On the Importance of Marxist Materialism, Communism as a Science, Meaningful Revolutionary Work, and a Life with Meaning, by Bob Avakian)

Below are some research notes on this horror show, made worse by the pandemic.

***

Fascism—and particularly the fascism of the Republican Party—is fanatically “pro-business” and anti-regulation. Before the pandemic, the regime was already pushing through deregulation to enable even more brutal exploitation on the part of the meatpacking industry—including granting “waivers” on legal limits to line speed at 14 poultry plants. The regime is viciously racist and anti-immigrant, and so, hostile to the masses who work in these industries, which now is more than 80 percent nonwhite, with large numbers of immigrants.

Coronavirus Tears Through the Meatpacking Industry

According to the Midwest Center for Investigative Journalism (MCIJ), as of April 30, there have been at least 6,300 confirmed COVID-19 cases linked to 98 meatpacking plants in 28 states, and the numbers have been growing rapidly. Most workers have not been tested, so the real numbers are certainly much higher.

So far, at least 30 meatpacking workers have died of COVID-19 at 17 plants in 12 states.

These mushrooming outbreaks have led to about 22 plant shutdowns lasting from a few days to two weeks. These shutdowns are partly driven by pressure from the workers, community activists, and local officials who see them as a way to reduce the spread of the virus and save lives. And partly they are driven by worker absenteeism that makes it difficult for companies to keep them running anyway.

In response, Trump is trying to curtail or stop these shutdowns as much as possible. On April 28 he issued an executive order declaring that such closures are “undermining critical infrastructure during the national emergency,” and ordered the Secretary of Agriculture to “take all appropriate action under that section to ensure that meat and poultry processors continue operations.”

Since then the governor of Iowa publicly stated that if workers don’t return when their plants reopen, they will be denied unemployment benefits! So these fascists are on the one hand pushing for epidemic-struck plants to remain open and then threatening workers who don’t go in with starvation.

A Brief History of the Meatpacking Industry: 100 Years of Barbaric Exploitation

In 1906, Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle shocked the country by laying bare the horrific treatment of mainly European immigrant workers in Chicago and other big city packing houses. That led to some modest reforms. Then in the 1930s unions organized much of the industry, conditions improved some and pay increased significantly. Through World War 2 and in the following decades the workforce changed to include more women and Black people.

Up through the 1960s and ’70s, meatpacking was a relatively well paid job, with wages around 15 percent higher than the manufacturing sector as a whole. But major transformations happened in the ’80s; according to PBS:

Developments such as improved distribution channels allowed meat packing companies to move out of urban, union-dominated centers and relocate to rural areas closer to livestock feedlots. [Industry powerhouses] sought to undercut the competition by operating on slim profit margins, increasing worker speed and productivity, and cutting labor costs. Such tactics encouraged industry consolidation, increased hazards for workers, and renewed resistance to employee organizing efforts.

So, the industry was transformed from urban to rural, unions were either weakened or gotten rid of, and a more vulnerable workforce was recruited. Pay dropped, conditions worsened.

Conditions in the Industry: “When We’re Dead and Buried Our Bones Will Keep Hurting”

There are over 400 thousand production workers in the meat- and poultry-packing industry, and those workers slaughter, process, and pack over 100 billion pounds of meat annually, which generates around $185 billion in sales, mostly for a few industry giants like Perdue, Smithfield, and Tyson. Tyson alone reaped $3 billion dollars in profits in 2018.

These workers are increasingly women, immigrants, and people of color. According to The Center for Economic and Policy Research, the people doing the most dangerous “frontline” jobs (like cutting, processing and packing the meat) are 44.4% Latino, 25.2% Black, 10% Asian and Pacific Islands, and 19.1% white; 42% are women; 51.5% are immigrants.

The average wage for slaughterers and meatpackers in 2018 was $13.38 per hour. This is 44 percent below the average for manufacturing as a whole.

Working conditions are horrendous. A 2017 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report cited by USA Today says that the accident rate is four times higher than for manufacturing as a whole.

Human Rights Watch (HRW)—in an article titled “When We’re Dead and Buried, Our Bones Will Keep Hurting”—reports that:

OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] data show that a worker in the meat and poultry industry lost a body part or was sent to the hospital for in-patient treatment about every other day between 2015 and 2018. Between 2013 and 2017, 8 workers died, on average, each year because of an incident in their plant.

HRW interviewed almost 50 workers in four states and reported that:

Most ... shared experiences of serious injury or illness caused by their work. Many showed the scars, scratches, missing fingers, or distended, swollen joints that reflected these stories. Some broke into tears describing the stress, physical pain, and emotional strain they regularly suffer. Almost all explained that their lives, both in the plant and at home, had grown to revolve around managing chronic pain or sickness. (Emphasis added)

In addition, Civil Eats reports that many packinghouse workers “already have respiratory problems, from the exposure to chlorine and peracetic acid, chemicals used for cleaning and disinfecting chicken, and such pre-existing conditions place them at higher risk” for COVID-19.

Treatment of workers can be incredibly degrading. Priority is given to keeping the line going at maximum speed; HRW reports that workers “described constant pressure from their supervisors to keep the line moving, sometimes with insults and humiliation. To ensure production speed, some workers said that supervisors even refuse to let them use the restroom during their shift or require them to wait for replacements who may never come, and described their colleagues wearing diapers as a result.”

And in terms of “social distancing,” the faster the line moves, the more closely workers must pack together—“elbow-to-elbow” is the term frequently used—to get the job done. The New York Times cites a former OSHA official saying (of the Trump administration and the meat industry), “They prioritize line speed production and traffic over worker health and public health.”

All of this explains why these packing plants were ripe for COVID-19 outbreaks. The director of Food Chain Workers Alliance told Civil Eats: “Exploitation of the food labor force is not something that has just [recently] come up. ... the exploitation they’re seeing at this moment is possible because it’s a pre-existing condition.”

Conditions Leading to the Outbreaks: “They’re bribing us to work sick...”

As the epidemic began to unfold in March and April, meatpacking companies took some half-hearted measures to reduce the spread, promoting handwashing and/or provided social distancing in parts of the plant. But they generally did not make protective gear widely available, and most importantly, almost never voluntarily reduced line speed, without which social distancing is impossible. (Sometimes they had to reduce line speed because of increased absenteeism, but even with fewer workers, most plants tried to maintain the same pace.)

Another major reason the epidemic spread is the general lack of sick pay so that workers—who often live paycheck to paycheck—could afford to stay home if they felt ill. According to Civil Eats, some plants did offer “short-term disability pay ... But that only amounts to a fraction of full-time pay.”

Even more outrageous, many plants offered a $500 “responsibility bonus” for people who worked a month without an absence. In other words, they incentivized people to come in even if they felt ill or unsafe and punished people who stayed home. Commenting on this, a Smithfield worker told the Sioux Falls Argus Leader, “I feel like they’re bribing us with money to come to work sick. That’s how you know they don’t care, because they’re forcing people to come to work. People are forcing themselves to come to work even when they’re sick.”

Two “Case Studies” in How Capitalism “Handles” a Deadly Epidemic in the Workplace

Here is how all this played out in two major outbreaks:

- The Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, was at one point the largest coronavirus hotspot in the U.S. On April 8 state health officials confirmed there were 80 workers who tested positive. The company responded by proposing a three-day shutdown (to start April 11) to “deep clean” the plant, and they started taking people’s temperature on entry and sent home workers who were sick. (But then insisted remaining workers take longer shifts to cover for them!). They established more social distancing, but not on the processing line or in the long, narrow, crowded locker room. They set up hand sanitizer stations.

- USA Today reported the following on the pre-shutdown conditions:

- A 50-year-old employee named John at Smithfield’s Sioux Falls plant told USA TODAY that there’s no way to stay 6 feet from co-workers on the production line, in the cafeteria or in the locker room. ...

- As people around him at the plant became infected with COVID-19, John said, he started feeling sick and went to get his temperature checked, thinking he needed to leave. But he was stopped, he said. “They told me I was OK and I needed to work,” said John, who has worked at the plant for a decade. “I said nope, and I came home.”

- In early April, he learned he had tested positive for COVID-19. “Those people don’t care about us,” John said. “If you die, they’ll just replace you tomorrow.” [Emphasis added]

- This plant was unionized, but instead of denouncing the shocking disregard for the health of workers, the union (UFCW) spokesperson praised Smithfield, saying that “Any of those precautions can make a difference. Even if 10 people get exposed in a day rather than 11. If you can implement a program where even one or two less people get exposed during a shift, that’s one or two less people getting infected and spreading it to their families.” (There was significant protest at Smithfield (see sidebar) but it was not organized by the union.)

- On April 13, the state revealed that the infected count was up to 238 and spiking higher over three days. (By May 1 more than 850 workers tested positive.) So the company agreed to shut down “indefinitely” after workers raised the demand for a two-week shutdown and after the Sioux City mayor and the South Dakota governor (both Republicans) wrote a letter asking for two weeks.

- At the same time, company officials countered in the realm of public opinion, claiming that the closure, “is pushing our country perilously close to the edge in terms of our meat supply.” And that “we have continued to run our facilities for one reason: to sustain our nation’s food supply during this pandemic. ... We are either going to produce food or not, even in the face of Covid-19.”

- The New York Times later reported that the Trump regime attempted to intervene to prevent the closure:

- When the Smithfield pork plant in Sioux Falls, S.D., became the nation’s largest virus hot spot in early April, the city’s mayor, Paul TenHaken, had a “heated” phone call with Smithfield’s chief executive, Ken Sullivan, Mr. TenHaken recalled.

- At one point, the mayor said, Mr. Sullivan had to drop the call to speak with the secretary of agriculture, Sonny Perdue, who was urging him not to shut down the plant.

- “It’s tense,” Mr. TenHaken said in a news conference at the time. “They’re being told by the feds to stay open.”

- Partly driven by Trump’s executive order, the plant is scheduled to partially reopen on May 4.

- The JBS plant in Greeley, Colorado. As of April 17, 100 workers tested positive, at least three of whom died, including Saul Sanchez, a 78-year-old Mexicano who had worked there for over 30 years. The plant closed on April 15—the day of Saul’s funeral—and reopened nine days later on April 24 without conducting widespread testing, instead promising “on the spot” testing of anyone showing symptoms. On the same day they reopened, JBS threatened legal action against the union for speaking out publicly about safety concerns.

- As is well known, coronavirus can be spread by asymptomatic people, and spreads quickly when people are packed close together. Moreover, nine days is not even enough time for the already infected workers to recover. So, surprise, surprise, on April 29 the union reported that there were 245 testing positive—more than double the number before the shutdown.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 epidemic in the meatpacking industry is a crime on top of a crime on top of a crime that needs to be further exposed and opposed. First, the pre-COVID (and pre-Trump) brutality and exploitation of these workers for profit. Then the practices that led to the rapid and unnecessary spread of the disease through these plants and wider communities, endangering tens of thousands. And now the insistence that these plants remain open regardless of the consequences for the people who work there or those who live in surrounding communities.

This is a crime, but it is also one that has met beginning condemnation and resistance, and may—and needs to—call forth much more. If there is one thing that the COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us, it’s that the future is unwritten and not fully predictable, but that human beings can have something to say about how things play out going forward.

Workers at a Texas beef plant cut meat from bones. Though likely taken before COVID-19, these kinds of conditions remained typical long after coronavirus began to spread in the U.S. and were a major factor in the epidemic of outbreaks in the industry.”

(Photo: Department of Agriculture)

Tyson workers process chickens. In the wake of dozens of deaths and thousands of illnesses, the meatpacking companies still insist on high-speed production with people working shoulder to shoulder – but now they claim minimal improvements like masks and dividers provide sufficient “protection” for the workers.

(Photo: AP)

BAsics, from the talks and writings of Bob Avakian is a book of quotations and short essays that speaks powerfully to questions of revolution and human emancipation.

“You can't change the world if you don't know the BAsics.”

Tyson Foods Plant

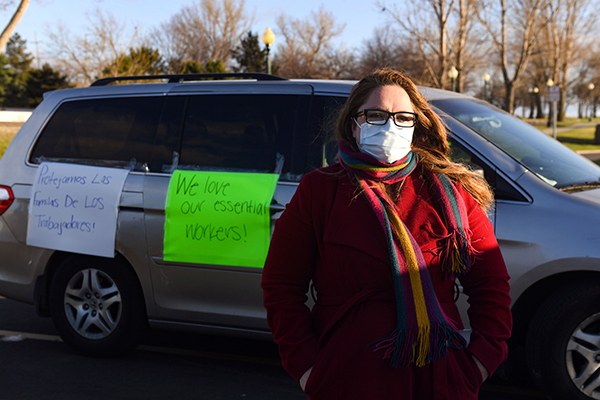

Nancy Reynoza of ¿Que Pasa? Sioux Falls, a Latino community group that organized an April 9 car caravan protest in support of Smithfield Food workers after it came out that 80 workers tested positive for COVID-19. The number would soon rise to 850. Dozens of cars took part. (Photo: AP)

Beatriz Rangel lays a flower on casket of her father Saul Sanchez, who worked at the JBS meat plant, Greeley, Colorado for over 30 years. She told reporters that as fear of the disease spread in the plant he felt obligated to work. “My dad was encouraging, he was loving, he was a hard-working man. Now he’s gone and I know they [JBS] do not care. It’s too late for my dad, but it’s not too late for the other employees.” (Photo: AP)

See also:

The Coronavirus Pandemic — A Resource Page

- What IS the coronavirus COVID-19 and what do scientists know about this?

- How is the capitalist-imperialist system making the effect of the coronavirus worse than it has to be?

- How do the “savage inequalities” of the system play out in the way this virus affects different sections of people? Who does it come down the worse on, and why?

- How would the revolution handle the coronavirus or similar epidemics if it held state power?

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: