Revolution #145, October 19, 2008

“Art and China’s Revolution”

at the Asia Society Museum

An Unofficial Guide to the Exhibit

Take the 68th Street subway exit on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and walk over to Park Avenue. Two blocks north, on the street divider in the middle of four lanes of heavy traffic, a 10-foot-high steel sculpture of a Mao jacket greets you. Then on the building to the right is a big banner with a drawing of Mao Tsetung surrounded by images of workers, soldiers and youth marching with red flags, Red Books and rifles. This is the outside introduction to a new exhibit at the Asia Society Museum titled: “Art and China’s Revolution.”

In the next couple of months, tens of thousands of drivers will zoom past the huge Mao jacket, prompting many to do a double take. It will jog some people’s memories back to the ’60s when millions of people around the world, including here in the United States, looked to socialist China as a truly liberating society. For some it might bring to mind Andy Warhol’s pop-art image of Mao, which you occasionally still see on t-shirts and greeting cards. After being bombarded by decades of being told that “communism is dead,” most people who drive or walk by will probably consider these artistic references as icons of “the failure of socialism.” But for those who actually go through the revolving glass doors of the museum and see the exhibit, this can be an opportunity to examine and think more about what Mao and the Cultural Revolution and socialism are really all about—and to look at, and reconsider, the “accepted wisdom” on the effect this historic struggle had on art and artists; and in turn, the role art and artists played in this historic struggle.

In the next couple of months, tens of thousands of drivers will zoom past the huge Mao jacket, prompting many to do a double take. It will jog some people’s memories back to the ’60s when millions of people around the world, including here in the United States, looked to socialist China as a truly liberating society. For some it might bring to mind Andy Warhol’s pop-art image of Mao, which you occasionally still see on t-shirts and greeting cards. After being bombarded by decades of being told that “communism is dead,” most people who drive or walk by will probably consider these artistic references as icons of “the failure of socialism.” But for those who actually go through the revolving glass doors of the museum and see the exhibit, this can be an opportunity to examine and think more about what Mao and the Cultural Revolution and socialism are really all about—and to look at, and reconsider, the “accepted wisdom” on the effect this historic struggle had on art and artists; and in turn, the role art and artists played in this historic struggle.

“Art and China’s Revolution,” which will run through January 11, 2009, focuses on the art produced during the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, from 1966-1976. It includes large-scale oil paintings, ink paintings, sculptures, drawings, artist sketchbooks, woodblock prints, posters and objects from everyday life. Co-curated by Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian, it is organized around the themes of: The Cult of Mao; To Rebel Is Justified; Never Forget Class Struggle; Up to the Mountains, Down to the Villages; and Art, History, and Politics. There is also a separate display about a Beijing-based art collective that in 2002 initiated the “Long March Project—A Walking Visual Display.”

“Art and China’s Revolution,” which will run through January 11, 2009, focuses on the art produced during the ten years of the Cultural Revolution, from 1966-1976. It includes large-scale oil paintings, ink paintings, sculptures, drawings, artist sketchbooks, woodblock prints, posters and objects from everyday life. Co-curated by Melissa Chiu and Zheng Shengtian, it is organized around the themes of: The Cult of Mao; To Rebel Is Justified; Never Forget Class Struggle; Up to the Mountains, Down to the Villages; and Art, History, and Politics. There is also a separate display about a Beijing-based art collective that in 2002 initiated the “Long March Project—A Walking Visual Display.”

This major cultural event will impact broad public opinion and critical and intellectual discourse on the subject of revolutionary art, and more generally the Chinese Cultural Revolution. A review of the show was featured on the front page of the New York Times art section the day it opened, where Holland Cotter wrote that “the important exhibition ‘Art and China’s Revolution’ at Asia Society poses its own different but perfectly timed post-Olympics question: What came before?” And to this I would add, when we go to the future, what should be learned from what came before?

This show comes at a time when, for the most part, the whole experience of socialism on this planet has been written off as a failure, as undesirable. And as part of this, the wonderful art displayed in this exhibit has been vilified and dismissed. But this art is a powerful chapter in the history of the Cultural Revolution. It sheds real light on the overwhelmingly positive achievements of socialist China. And it is terrible that people throughout the world have largely been denied the chance to see and appreciate this revolutionary art. So now, it is really good that these works are on display at a major, prestigious museum in New York City. And people should make sure they take advantage of this rare opportunity and go see this display.

The aim of my commentary here is not a critique of “Art and the Chinese Revolution” (although that is needed and is forthcoming). What I offer now is some thinking on the larger context in which the art in this show was originally produced. I hope this will help people understand the significance of this art and this show, encourage people to go see this display, and serve as an “unofficial” guide to the exhibit.

A show about Mao, art and the Chinese Revolution is bound to be controversial and contentious. The exhibit itself expresses a certain political perspective. The people who visit this exhibit will come with their own viewpoints. And this show is not happening in a vacuum. It is happening 30 years after the death of Mao; after three decades of anti-communist propaganda that declares the Chinese Cultural Revolution a human disaster and tragedy. And there is a great deal of confusion about the nature of the China that existed under Mao and the China that exists now.

Most people think China is still a socialist country. But China today—its government and the whole character of its society—is thoroughly capitalist, even though it continues to call itself “socialist” and its leaders continue to call themselves “communists.” After Mao died in 1976, his opponents in the top ranks of the Chinese Communist Party, headed by Deng Xiaoping, seized power, overthrew socialism and restored capitalism—arresting hundreds of thousands and killing thousands in the process.

When you go through this exhibit there is a timeline that chronicles some of the major turning points in the Cultural Revolution—but the actual content and character of these events (and the struggle overall) is either missing or distorted. So viewers get no real context in which to understand the art they are seeing. So in this light, here is an unofficial guide to help you get the most out of seeing this exhibit:

1. Really Look at the Art

Walking through the exhibit you are struck immediately by the exuberance of the work. The brilliant palette, reds and yellows, jumps out. This is work reflecting times of great vitality. It has the feel of the ’60s throughout the world. The figures depicted, from Mao Tsetung to the peasants, the youth and artists, have a presence. This should, at the very least, be cause to look deeper into this work and the stories behind it.

I have been to the show two times now and noticed from hearing nearby comments that, unfortunately, some people tend to overlook the art itself and focus more on the show’s narrative—which gets melded onto their own preconceived prejudices. I heard one woman declare, looking at a wall of art, “this was all destroyed by Mao.” On one level, this is just ridiculous—the show itself is testimony to how this art was created and promoted as an important part of the Cultural Revolution, and the important role of artists during this whole struggle. Yet this woman was “seeing what she wanted to see”—letting official anti-communist verdicts completely blind her to the story the art itself was telling and the artistic quality of this work as art, as well as its actual historical and political significance.

So the first thing I want to say to people who plan to see this exhibit is: Really look at and experience the art and the times it represents.

Part of the anti-communist grand-narrative of the Cultural Revolution is that artists were stifled and persecuted and that cultural work was lifeless, didactic and highly controlled. This is a completely false rendering of what was being attempted and what actually happened with regard to art during the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, there were real problems in how the revolution-aries approached issues of art and culture. For example, there wasn’t enough air for artists to breathe and experiment, to strike out in different directions, including creating art that represents dissent. And there was also a related problem of practices and policies reflecting a wrong view that the way to deal with reactionary art is to just “outlaw” it.

But these problems, while real, were secondary to the real advances and breakthroughs made in building a revolutionary culture—where professional artists and the masses of people, formerly locked out of this realm, were unleashed to create tremendous revolutionary works of art. And all this was taking place in a larger society that was breaking out of the vise-grip of class exploitation.

A major theme in the show is how artists were sent to the countryside to work alongside and learn from the peasants. This is mistakenly seen by many people as a way artists were stifled and punished. But in fact, this was an important part of tackling the lopsidedness of resources between the cities and countryside, and breaking down barriers between intellectuals and peasants and workers. While there were problems with some of the policies with which this was carried out—for example there weren’t sufficient avenues for professional artists to work in more concentrated and focused ways—this experience contributed to the creation of important works of art and the development of artistic techniques. The exhibit includes some beautiful paintings and drawings by artists who “went to the countryside.” One of these is by Xu Bing, who is now the vice president of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China. The catalog explains: “The experience was mostly a positive one as he was free to pursue art and spent much time drawing from nature after his day of work in the field was over. His exposure to local cultures, propaganda art, and calligraphy during the Cultural Revolution had a strong influence on his artistic philosophy and methodology.”

This complexity of creating revolutionary art can be discerned by someone who approaches the show with an open mind. And something very real comes through in the art in this exhibit, which reflects the truth that socialist China under Mao represented a real advance in human history in terms of the theory and practice of building a society in which the masses of people are involved in revolutionizing all aspects of society with the aim of getting rid of classes and all the inequalities and oppressive ideas that go along with class society.

It is a very powerful and moving experience to actually see these works of art. And much of what is in this show is of a very high artistic quality.

Back in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I was one of those youth in the United States who, inspired by the Chinese Cultural Revolution, carried a Red Book in my back pocket and put posters of Red Guards on my bedroom wall, alongside glossy reproductions of Peasant Paintings from Huhsien County. In 1970, I bought the book Rent Collection Courtyard, and pored over the photos of the “Sculptures of Oppression and Revolt.” But seeing the actual paintings, woodblock prints and sculptures was a whole other, sensory, cultural experience. It reminded me of how, after seeing the calendar reprint of Starry Night by Van Gogh a hundred times, I went to a museum to see the real thing and was simply blown away by the tremendous artistic forte and tactile depth of the actual oil painting.

|

| Chen Yanning, Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside. 1972. Oil on canvas. |

Many of the art pieces in this exhibit give you an important sense and visual understanding of Chinese history—what it was actually like for the masses of people in China before the revolution and what society was like after liberation. The form and content of the art gives you a real sense of the tenor of the times and the stakes of the struggle. You see slices of what the revolutionaries were trying to do, for example the Great Leap Forward, which was an attempt to revolutionize not only production but also all the economic and social relations between people, and the very thinking of people.

When I walked into the room with Chen Yanning’s huge painting, Chairman Mao Inspects the Guangdong Countryside, I literally had to catch my breath. This was one of the pieces of art I was familiar with—but seeing the texture of the oil on canvas and the actual palette of colors was a whole different experience. The form and content of the painting really struck me—the size of the canvas emphasizing the historical weight of the countryside (and the peasantry) in Chinese history; the position of Mao in the center of the tableau underscoring his leadership and the way he did deep investigation among the peasants.

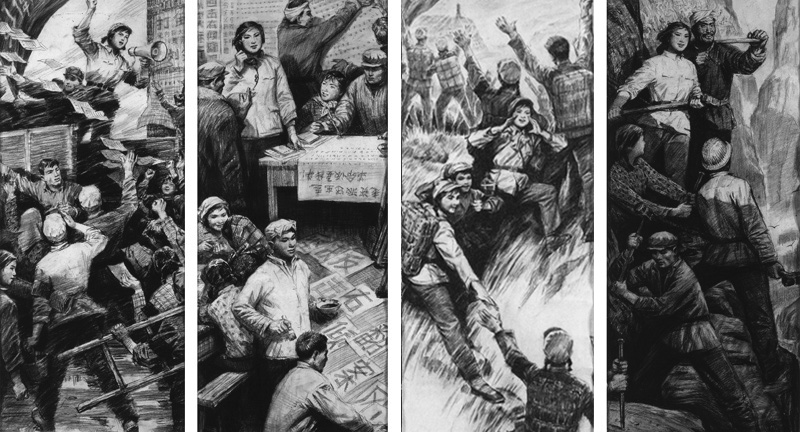

One of my favorite pieces in the show is four panels of charcoal drawings, depicting Red Guard activities during the Cultural Revolution. The vitality of the drawings pulls you into the excitement of the scenes and the exuberance of the characters jumps out at you. These beautiful images of young people, including women—taking up theory, going out among the masses, setting out to build a new society and change the world—are alive with the times.

Another piece I really liked was a woodblock print of a man teaching a young girl to write...simply titled, Revolution. The historic weight of what this represents is conveyed so eloquently: What did it mean for cross generations of formerly poor, illiterate peasants to be reading as part of becoming conscious makers of history?

The works of art in this exhibit, in many ways, speak for themselves. They should make even cynics wonder about what the revolution in China was all about and why it unleashed so many people to produce works of art like this.

2. Think About History

The descriptions and commentary on the walls of the exhibit are mainly informative and, for the most part, don’t attempt to insert an anti-communist “slant” into the descriptions of the artwork. At the same time, there is a thread of a subtext here that will connect with what most people mistakenly believe—that the main thing about the Cultural Revolution is that people suffered, artists in particular were persecuted, and Mao didn’t care about the people. For example, the show’s introduction says that during the Cultural Revolution, “sometimes referred to as the decade of catastrophe,” artists were “subjected to public humiliation and sometimes torture, and their homes and artworks were seized and destroyed.”

|

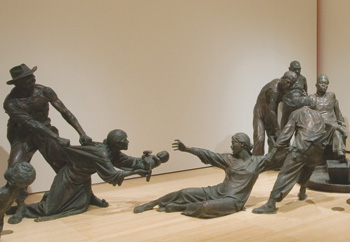

| Rent Collection Courtyard. 1974. Fiberglass. |

In the “To Rebel Is Justified” section of the exhibit there is a room with several life-size recreations from the Rent Collection Courtyard. The explanation on the wall says: “The obvious exploitation of the peasants is designed to remind viewers of the unfairness of feudal China, thereby providing justification for revolution.” This commentary shows no understanding of the immensity of history these sculptures represent. And when I read this, I couldn’t help but think about how a lot of people have absolutely no idea what this meant for literally hundreds of thousands of people—of how “not being able to pay the rent” was the thin line between living and starving to death; it meant having to sell your daughter or having to become a bonded slave. And sadly, such a view prevents one from really appreciating the sheer artistry of these sculptures. Go and look at the detail in the faces, what this art captures about the human emotions of the suffering, anguish and rebellion; how the silent body language of these figures brings to life a whole period of Chinese history—and why such a revolution was necessary to begin with.

The original Rent Collection Courtyard included over 100 life-size clay figures, originally displayed in 1965, in the actual former rent collection courtyard of Liu Wen-tsai—a tyrannical landlord of Tayi County, Szechuan Province in southwestern China. Before liberation only three or four percent of the local population of Tayi were landlords, but they owned almost four-fifths of the arable land—and the peasants were mercilessly exploited and treated like beasts of burden. This was typical in China at the time, where poor peasants made up the overwhelming majority of the population. The group of 18 amateur and professional sculptors who created the Rent Collection Courtyard during the Cultural Revolution, went to live and work in the actual courtyard and talked with the people who had suffered in the old society.

When people go to this show, they should keep in mind how this art was created in the complex and intense cauldron of ten years of an immense and unprecedented effort by hundreds of millions of people to build a new and liberating society in a very poor country, still subjected to the deep scars of feudal inequalities. This was a country not that far from a time in which the vast majority of people were starving and illiterate; a country dominated by foreign powers, with gaping inequalities—between mental and manual labor, town and countryside, and men and women. Yet here they were, not just feeding and clothing people, but mobilizing hundreds of millions of people to consciously take up all the huge economic, social and philosophical and practical questions of how to get rid of class society.

This is the context people should think about when they go see this art show—not the “grand narrative” and summation of the Cultural Revolution that has been issued by the defenders of capitalism in the West and the enemies of Mao who overthrew socialism, brought back capitalism, and now preside over a China today that offers up the masses of people to the sweatshops of global capitalism.

Think about if you went to a museum exhibit about the history of the U.S. Civil War—and found yourself treated to a whole “reinterpretation” of the war through the eyes of a former slave owner—who is whining and crying about how he lost his plantation, how his private property, most importantly, the human beings he owned, were taken away from him, and how his whole family has suffered because of this.

This is like going through an exhibit and seeing a photo of the back of a slave, completely covered with layers of deep, thick scars from being whipped; hearing stories of how slaves were hunted down like dogs and killed when they tried to escape, how whole families were separated—and then being told, “this has been used to justify the struggle against slavery.” You would get a totally skewed view of this period of history—and might end up sympathizing with the former slave owner about his “personal loss” and because of this and from this narrow view, conclude that the U.S. Civil War that ended slavery was one of the most “catastrophic” periods in U.S. history.

Think about this analogy. And then think about what Mao and the revolutionaries he led were trying to achieve in this relatively brief period of 30 years, after the revolutionary seizure of power in 1949 and before capitalism was restored in 1976. Human beings on the planet didn’t have a lot of experience in trying to build this kind of society—a transitional society aimed at bringing into being a communist world free of classes. Mao learned from the experience of the Soviet Union and made tremendous theoretical breakthroughs in understanding the nature of socialist society. In particular he pointed out that classes and class struggle continue under socialism and that sharp struggle continues over the whole direction of society, whether it will stay on the “socialist road” or end up bringing back capitalism. And this is why Mao launched the Cultural Revolution. Mao was not inventing enemies. Powerful forces in the communist party were organizing to take power and bring back capitalism. And if you go through this exhibit and think Mao was paranoid—take a look at how today China has become a sweatshop paradise for international capitalism.

|

| Zhang Songnan, Youth. 1972. Charcoal on panel. |

3. Enter with a Clear Mind

I suggest that before people see this exhibit, they clear their mind. Go through the exhibit, take in the art and let it wash over you. Walk through slowly and see what you think about the art as art. And at the same time, think about the big questions this exhibit—and the chapter in human history it is a slice of—raises.

Reflect on the important role art and artists have played throughout the history of human society. And think about this: What would it mean to create a revolutionary culture as part of building a truly liberating society? Put yourself in the shoes of revolutionaries who were trying to accomplish something that in the history of humanity had never been done before. Consider the ways in which this question takes on new meaning in a revolutionary, socialist society that is aimed at enabling the masses of people to, as Marx said, consciously understand the world in order to change it.

Think more particularly about the kind of oppressive society that Mao was leading people away from and the reality that before the Cultural Revolution, the masses of ordinary people were not on the stage or the gallery walls. Instead there were, as Mao put it, “emperors, generals, beauties and foreign mummies.” What effect did that have on the ethos and social consciousness throughout society? By analogy, what did it mean in this country when the minstrel show and Amos and Andy were the representations of Black people in the arts?

When you look at the political posters, don’t just have a knee-jerk reaction to them as “political propaganda.” Think about what role such art played in a society where hundreds of millions of people were discussing and debating economics, politics and philosophy—that really mattered in terms of what direction society was going to go; and judge it partly on that basis. And think about how crucial things like “Big Character” posters were in a society where most people didn’t have a TV, where many were still semi-illiterate, and there certainly wasn’t anything like the Internet!

When you look at all the Mao buttons and posters, think about why hundreds of millions of poor peasants, workers, youth and yes, intellectuals revered Mao for the leadership he gave that was crucial in the war of liberation and the building of a new society.

4. Think About the Big Questions

The creation of revolutionary art in China posed huge questions. For instance, how do you develop and promote conscious, collective efforts in creating works of art broadly among the masses while, at the same time, appreciating, supporting and learning from the work of individuals and more highly trained artists—including those who are creating works of art that represent disagreement and dissent? If you are leading a broad movement to create revolutionary art, how do you balance the need to create “model works” that need more finely calibrated leadership—while at the same time, letting things go far and wide, in all directions—including giving full scope to works of art that go in a dissenting direction or that may not have any direct relationship (either objectively or consciously) to politics? And there are huge issues about struggle in the artistic realm; the ways artistic political struggle and criticism is carried out; and the particular policies and practices with regard to artists and the development of revolutionary art. (For example, the exhibit talks about “black painting” exhibitions of art that were “held up for denigration”—something which should be investigated, understood and evaluated.)

Before or after you go to this exhibit, read some of Bob Avakian’s work, like Observations on Art and Culture, Science and Philosophy, which examine how these kinds of questions were handled under socialism in the Soviet Union and China—learning from this previous revolutionary experience, but also synthesizing the lessons, both positive and negative, from this, and pointing to the ways in which future socialist societies have to do better.

5. Recognize and Play with the Contradictions

This exhibit pulses with positive and negative tension. There is dissonance within the exhibit itself, contradictions within the exhibit itself.

Play with the very contradictoriness of the show itself—and the complexity of all the different, big historical questions that are raised by the art and the larger historical context in which this art was created. Again, put aside pre-conceived notions and prejudices and suspend for the moment what you already “know”—and this equally applies to those who have a positive view of Mao and the Cultural Revolution. Examine and wrangle with all the contradictions, get some discussion going about this with other people, and together dare to look at things with “fresh eyes” and discover or re-discover some new things.

6. Have Fun and Spread the Debate and Discussion

This art show, left to spontaneity, will in many cases end up reinforcing much of the official, anti-communist conclusion that this period in Chinese (and human) history is proof that “communism is dead.” But the real truth, which this art show actually depicts, is that socialist China achieved great things. It came up against real problems, some of which were dealt with and solved in a good way, and others which were not. And how could it have been otherwise? The socialist experience in China really did take humanity a certain distance along the road to achieving an emancipating world—a path that people on this planet must continue to travel. And there is the potential for this show to open up new rounds of discussion, examination and appreciation for what socialist China achieved, including in the particular realm of art—and the necessity, possibility and pathways for how humanity can do even better in future socialist societies.

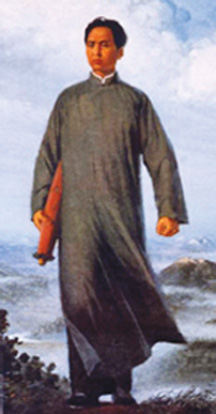

Liu Chunha, Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan. 1969 poster. |

I think one of the highlights of the show is the video of a 2007 interview with Liu Chunhua, the artist who did the famous painting, Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan (included in the exhibit). During the Cultural Revolution over 900 million copies of this painting were printed. At the very end of the transcribed interview in the book Art and China’s Revolution (published to go with the exhibit), the interviewer declares that the “so-called Cultural Revolution can be counted as a dark age in the history of twentieth-century China” and then asks, “So, how should we treat the works of that period that serve to extol and eulogize [it]? Where does their value lie?” And Liu answers:

“This is an extremely sensitive question. In reality, the Great Cultural Revolution was a political struggle. The history of political struggles is always a case of ‘either you or me.’ Today, the Cultural Revolution is considered to have been a catastrophe. Many people suffered great injustice, many families were destroyed; it was truly a tragedy. When I was on a research trip in North America, I met a third-year secondary student in Canada whose grandmother lived in Taiwan. During the Cultural Revolution, his family’s home had been ransacked countless times. One can only imagine the hardship and suffering his family went through. After the period of reform and opening [to the West], his grandmother paid for him to study in North America. During my meeting with him, I very spontaneously expressed my deep sense of regret. I said to him, ‘Mao Zedong allowed these crimes to be committed against you.’ But he didn’t think of it in that way. He said to me, ‘It wasn’t Mao Zedong who made us suffer, it was the people whom Mao Zedong was against who made us suffer.’ So we can see that any historical phenomenon is extremely complicated. Looking at the history of the proletarian revolution from a sociological perspective, whether it [the Cultural Revolution] has furthered the interests of the proletariat is a question I believe will need to be evaluated through future discussion of the history of the Cultural Revolution.”

Go see this show. Don’t miss the opportunity to experience this art. Think about, discuss and debate with others the important questions raised by this exhibit—and the whole period of human history that produced this art.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.