Revolution #151, December 28, 2008

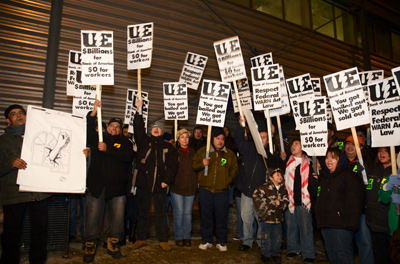

Workers Occupy Republic Windows and Doors

Friday, December 5, the men and women working at Republic Windows and Doors began a sit in at the Republic factory on Goose Island in Chicago, Illinois. Just that Tuesday they had been told that Friday would be their last day of work. They were told that Bank of America had refused to extend credit to the company and so the factory would have to close.

|

|

| Photo Credit: Jhonathon F. Gómez |

During the height of the housing boom Republic had employed more than 700 people—making windows for homes throughout the U.S. and Canada. And right now, it’s not that the world doesn’t need windows and doors. People working at Republic had made windows for repair of homes in Mississippi and Louisiana that had been damaged by Hurricane Katrina. But no capitalist is in business to make something just because people need it—they are in business to make profit. Over the past year more and more people had been laid off as the “housing bubble” collapsed and production was further automated. So people who make needed windows and doors are kicked to the curb when there is no profit to be made. One worker said that at the end there were places where one worker was producing as much as three had done previously. The company went from selling $4 million in windows to only selling $2 million in windows—and with credit tight and no upswing in homebuilding visible on the horizon the bank pulled the plug.

|

|

| Photo Credit: Jhonathon F. Gómez |

There was already a deep distrust that people working there had for the owners of the company. Leading up to the notice many had been working lots of overtime, building up the inventory of products. At the same time, for weeks leading up to the final announcement, important equipment had been disappearing from the factory in the dead of night. People had a good sense that something was going to happen and they talked about what they should do.

When the owners announced the final closure the remaining 240 people working at Republic were, overall, people with the most seniority—people who had poured their daily lives into the coffers of Republic for one, two or even three decades. Although not high paying, these were stable jobs, and many of the workers have been able to buy homes and have heavy financial obligations such as mortgage payments and kids in college. “Do you think it’s going to be easy for me to get another job?” asked a Mexican worker that had been there for 34 years. Republic owed people weeks of vacation pay and workers there were facing an immediate end to their healthcare benefits. Republic simply ignored the legal requirement to provide 60 days notice or 60 days pay before closing the plant.

What the Republic workers decided to do was refuse to leave the factory. A number of them thought it was going to be a short lived civil disobedience action—for which they would go to jail—but they had to stand up. And that decision—to fight—was welcomed far and wide.

It has become rare for people to stand and fight. One of the union organizers helping out at the occupation of Republic told us how, when they first called the press to announce the sit-in, many news outlets couldn’t believe it and thought they were joking. People are being laid-off across the country and, sad and frustrating as that may be, it is the way capitalism works—and people are used to accepting it.

|

|

| Photo Credit: Jhonathon F. Gómez |

In the end, Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase Bank agreed to loan the company the money to pay severance and vacation pay, and to keep up the health benefits for two months—what was owed to the workers. And the occupation has now ended. But people are still wrangling over questions thrown up by the occupation.

* * *

As we spoke with many of the Republic workers in what went from a sit-in to a 6 day occupation of the Republic Windows and Doors factory we found the main motivating factors were two fold—first, people were determined to get what was owed to them. Second, they wanted to set an example to people that you have to stand up—they wanted to inspire people to take actions themselves. And they wanted to keep their jobs.

People were inspired. People came from all over to support and take a stand with the people working at Republic. They came down to the factory from many different neighborhoods and suburbs of Chicago—and beyond. Flowers were sent from Alaska. A group of youth, led by a young man with the International Workers of the World came up from St. Louis, Missouri. A 72-year-old man who had worked in the building trades in his younger years came from a small town 60 miles away. A small software design company closed up for lunch so that people working there could come out in support.

At least two collectives of young Chicago anarchists were at the plant regularly. The Mexico Solidarity Committee and the group Latinos United came out. A group of day laborers from the San Lucas Workers Center showed up—with some of them describing how they had ended up working “casual labor” after being laid off in situations similar to what the owner was doing at Republic.

|

|

| Photo Credit: Jhonathon F. Gómez |

Messages poured in from around the country and around the world as well —messages from France and England and Spain. Republic workers were members of the United Electrical Workers Union Local 1110, and unions from all over the world sent solidarity messages. Several interfaith prayer vigils were held at the gates of the factory with clergy coming from as far away as Indianapolis, Indiana to express their support. All day long and into the evening people came by the factory to bring food, water, money and blankets—and to stand in support of the action. Youth, factory workers, film makers, college professors, students, ministers and rabbis.

There was another international aspect to this occupation as well. The people working at the plant included Blacks and whites, but overwhelmingly Latino. They had ended up in at Republic after coming from Honduras, Costa Rica, Uruguay, El Salvador, Mexico, Ecuador, Cuba and Puerto Rico.

In the face of a deep economic crisis—and with banks, including especially the Bank of America receiving billions of dollars from the government in an effort to keep that crisis from deepening—many, many people identified with and felt the justice of the action at Republic.

A 40-something disabled woman from a nearby suburb north of Chicago, who brought food and money in support of the take over, told us, “I know what it means to not have enough; I know what it means when you have to live close to the edge,” and told us “Their children is what brought me down here.” As she spoke, she was barely keeping the tears back. “I know what it means when parents can’t do what they need to do.” Her father had been an activist in housing struggles many years ago. She was about five at the time and the events at the factory brought it all back to her. Her mom had to sneak medicine through the police lines for her father. She said that she couldn’t believe how little had changed since those days. “You don’t have to be poor to know that too many have taken too much for too long.”

It seems that the owner of Republic had no interest in keeping this factory running because there was little chance of it turning a profit under current conditions. In fact, the family that owned the company has bought a non-union plant in Iowa where they could pay a smaller workforce two to four dollars less an hour without a union or union benefits.

During the six days of the occupation there were long periods where supporters stood around—in the entry way or at the door. There was a sense that a continuous physical presence of support was important to hold off any moves to force the workers out. And during those long hours there was a lot of talk about the economic crisis—where does it come from and what will be required to get to a society where people are not thrown out like trash? Many workers at Republic immediately saw the connection between their struggle and the story of Addie Polk, a 90-year-old Black woman who tried to kill herself when the sheriffs came to evict her from her home. Copies of Revolution Newspaper were inside the factory and being read by workers and supporters.

Some of those who came to the factory in support were open to the argument that this was not a case of “capitalism being broken” but rather “this is how capitalism works.” And there was debate over what could replace capitalism. Is revolution even needed? Couldn’t people just take over the factories and that would solve the problem? Is communism possible and/or even desirable? Workers and supporters alike got exposed to Bob Avakian’s new synthesis and there was back and forth over questions of human nature and totalitarianism. Copies of COMMUNISM: THE BEGINNING OF A NEW STAGE: A Manifesto from the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA were welcomed by people that were struggling with their sense that capitalism has to go—but is there a serious alternative? Some of the workers were influenced by the model of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, or by movements by workers in Argentina to take over factories and run them themselves. After some struggle, a worker wearing a Che Guevara baseball cap bought a copy of the new RCP Constitution and got a copy of COMMUNISM: THE BEGINNING OF A NEW STAGE: A Manifesto from the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.