A Revolution Club Discussion on the Special Issue on the History of Communist Revolution

December 16, 2013 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

From a reader:

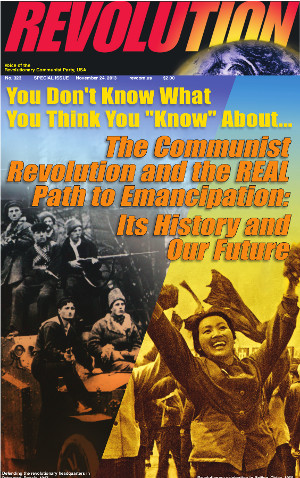

The other day I got together with a newly forming Revolution Club in an oppressed area to talk about the special issue of Revolution: You Don't Know What You Think You "Know" About... The Communist Revolution and the REAL Path to Emancipation: Its History and Our Future. This was a small grouping of Black and Latino people of different ages. Some people felt more comfortable talking in a group than others, but all were part of the discussion, and most had read some of the special issue. We opened up the discussion asking if there was any one part people read they wanted to discuss, or if there were things they've heard about the history of the communist revolution when they've been out talking to people that they hadn't known how to answer and wanted to learn about.

One young person said she had been out at a concert promoting the special issue and a drunk guy came up to her and told her people had starved to death in the Soviet Union during socialism. So, she wanted to find out about that. Right away, one of the other people in the discussion responded, "People were starving before they made revolution, that's why they made the revolution!"

Before getting further into this, the conversation turned briefly to some things on people's minds about the police. One person talked about how upset she was about finding out how much police presence there is inside high schools and wants to wage a fight to get them out. Another woman described the police presence at a nearby university, and we all talked together about the role of the police and how they enforce divisions between people, including acting in a way that teaches students who come from a more privileged background to hate and fear those on the bottom of society, and especially for white people to look at Black and Latino people as dangerous criminals.

In returning to the special issue we decided to start by reading the part of the interview with Raymond Lotta, "Radical Changes: Minority Nationalities," in contrast to the kind of situation we were just discussing. In this section we went through the meaning of some of the words some people were unfamiliar with: Bolshevik, autonomy, chauvinism. None of the people in the discussion had known before reading this issue that there were oppressed nationalities in Russia, and especially so many of them! They were struck with the contrast of how in the USSR (Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics) people were being led to struggle against "great-Russian chauvinism," while in the U.S. the Klan was marching in Washington, D.C. in full regalia.

Reading this section led to a short discussion of anti-Semitism—because working to do away with this was an important part of what was happening in the Soviet Union. One older Black woman wanted to know what were the origins of anti-Semitism and as a Christian whose father was a pastor was kind of horrified to come to the recognition that much of this comes from the Biblical portrayal of Jews as the Christ-killers. She had once traveled to Germany and talked about what it was like to visit Auschwitz—one of the concentration camps. Other people in the discussion didn't really know anything about what happened in Nazi Germany, so she explained how Jews were put in these concentration camps, tortured, and killed there in gas chambers. She said the feeling of walking into a place like that makes you think about how people could do this to other human beings. This was something we returned to later in a different way: the question of whether human beings can be different and whether or not there is a human nature that causes people to treat each other with such cruelty. The discussion about Nazi Germany was also a stark contrast to what we were reading about what had been happening in the Soviet Union, and I pointed out that the first people the Nazis went after in Germany, even before the Jews, were the communists: the force that could have actually led people to rise up against and defeat the Nazis.

When we got back into reading the interview, we read the parts on "Constructing a Socialist Economy," "Struggle in the Countryside," and "Changing Circumstances and Changing Thinking," to address the question raised about people starving.

When we read the part about collectivization of agriculture, people wanted to talk more about what was the struggle over this: who were the kulaks and where did the opposition to collectivization come from. I explained, drawing from the article, that the kulaks were the rich peasants, who owned land and were more privileged. Collectivization meant taking away some of that land and privilege so that more land was in the hands of the people collectively to be worked on to meet the needs of the society collectively (so that there would NOT be people starving!). The kulaks didn't want their land taken away and thus opposed and resisted collectivization. The woman who had traveled to Germany said, "I could see why they would feel that way," even though she didn't think it was good they were opposing collectivization. She went on to say that she thinks it might be a characteristic of human nature to feel that way. I said it's not true that it's part of human nature for people to want more than others around them. She said she didn't think it was "wanting more than others," but resenting other people getting something they didn't work for, when you did work for it, that is human nature. And she was raising all this from the standpoint of trying to imagine a future world where these kinds of relations are no longer in place, and having a hard time doing so.

The young woman who had asked about people starving said that these ideas come from how we have been trained in this society, how we are taught to think about things. I agreed and went on to talk about how this kind of thinking is also generated from the way capitalist society works. I gave a hypothetical example of two business owners who want to fairly treat their workers and agree with each other to do that, not to try to get extra profit for themselves. But then, there's somebody else somewhere else in the world, (because it is a global system of capitalism) or even some other part of the country, that starts producing the same thing and paying the workers less so they can make the product cheaper. When that product starts taking over the market, the two business owners then are forced to cheapen their product or else they will eventually go out of business. This drive to compete comes out of how capitalism works, and colors everything in this society, is promoted in the culture and in society in general, and becomes the way people interact in all relations, even the most intimate, for example looking at other people for what you can get out of using them, or women competing and fighting each other over a man.

The woman who said she thought it might be human nature said she could see this about capitalism, but has such a hard time envisioning anything else because she's lived in this capitalist system so long. This brought us back to the interview, about the way people's thinking needs to change to build a new society. We looked at how the other problem with collectivization in the Soviet Union was that the work hadn't been done ideologically, to transform people's thinking, and this was brought home by the quote from Mao: "What good is state ownership of factories, warehouses, if cooperative values are not being forged?" When the woman who had been asking about all this brought up how people don't think this way, a young guy in the discussion answered that we have to struggle with them, to transform their thinking.

The discussion of the special issue wrapped up on that point, with people being appreciative of talking about this together and being able to learn from each other, and then had some discussion about the BA Everywhere campaign, planning fundraising activities and future discussions.

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.