Particle Fever—Must-See Science Documentary Film

April 7, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

From a reader:

Three cheers for Particle Fever, the science documentary that opened in theaters across the country in March. Particle Fever is at once a spectacular presentation of the world's largest science experiment, a window into the lives of working scientists and what motivates them, and a subatomic thriller with a climactic ending.

The subject of the film is the Large Hadron Collider and the search for the elusive Higgs boson particle. But you don't have to know a boson from a bison to get immersed in this scientific detective story. The infectious enthusiasm of the scientists who propel the story will draw you in and make you want to know more.

The Large Hadron Collider, called the "LHC" throughout the film, is a circular particle accelerator 17 miles in circumference, built underground near Geneva, Switzerland. It is so large that parts of it are actually under two different countries (France and Switzerland). It cost about $5 billion to build and has a staff of 10,000 engineers and scientists.

Over the years, nuclear physicists have found a surprising number of "basic particles"—subatomic particles that seem to be the fundamental building blocks of all matter. And rather quickly scientists saw how these particles could be arranged in a table according to similarities (or opposites) of their basic properties. This schema is called the "Standard Model."

If there is one thing that scientists hate, it's a pattern with a missing component—a hole in the plan. And that's just what physicists found with their Standard Model of fundamental particles. There was a missing particle needed to fill out the table. The particle was informally named the "Higgs boson" after British physicist Peter Higgs who, in 1964, first suggested its existence. Scientists theorized that the reason the particle had not been seen up until now was that it was very massive.

When physicists talk about massive, they are not talking about being big. For physicists, the mass of a particle is its ability to resist any change in its motion. You have to apply more force to accelerate a massive particle. At the same time, mass and energy are two forms of matter, so that mass can be changed into energy (as when an atomic bomb explodes) and energy can be used to create particles (which is what can happen when scientists slam particles moving at near the speed of light into each other). It takes a great deal of energy to create a massive particle.

Particle Fever tells the story beginning in 2008 of the quest for the Higgs particle through the activities of six scientists working on the problem. What makes this fun is that the six are divided into three theoretical physicists and three experimental physicists. The theorists sit around in offices scribbling on chalkboards; the experimentalists wear hard hats and sit at control panels or climb down into the bowels of the LHC to tinker with its innards. It is also important that two of the six are women, smashing the stereotype that women scientists are always biologists while only men can do physics.

Right at the beginning of the film, the narrator, Johns Hopkins physicist David Kaplan, answers a fundamental question from the audience: "What are the practical results of this work? What of value will we get from all this money and effort?" Kaplan responds, "Maybe nothing, other than understanding everything." This sets the tone for the whole film. These scientists appreciate the importance of humans understanding the material world, even when there is no immediate or specific impact on our day-to-day lives.

The film then jumps to clips from American TV newscasts showing a couple of troglodytes in the U.S. Congress voting down money for a similar collider in the U.S. One literally states that finding out the basic laws of the universe is way down on his list of priorities. Kaplan observes: "I watch our political leaders on television, and I think, wow, truth has zero social capital." But he adds that at the LHC, "Here's a bunch of people that are in pursuit of something so pure. We are not going to get famous or rich, but we all feel great when we know something that's true."

If there is one thing that annoys the scientists in this film, it's having the Higgs boson referred to in the media as "the God particle." This sobriquet panders to the prejudice that anything really, really basic must be connected to a god in some way. It's not.

The fun part of the movie is watching the scientists at work and at play. There is no dress code and they all walk around carrying their laptops, showing each other their screens. As big moments approach (for example, the day when the LHC was first turned on), they get positively giddy. As one young woman scientist observed, they are like a bunch of six-year-olds whose birthday is next week!

And when they are not working we see them jogging, cycling, playing table tennis, partying with physics raps (I kid you not), playing the piano, or doing physics tricks for their children (don't miss the glass full of water upside-down trick).

There is also the friendly banter between the theorists and the experimentalists. At one point, an experimentalist tells one of the filmmakers, "Don't listen to the theorists!" And when the LHC has a massive accident shortly after it starts up, we eavesdrop on a group of LHC scientists trying to figure out how to do damage control with the media.

The drama plays out as the power of the machine is progressively cranked up. It has two beams of protons whizzing around the 17-mile track, guided by superconducting electromagnets cooled by liquid helium. The idea is to take two beams traveling in opposite directions and smash them into each other. Only in this way will enough energy be brought to bear in one tiny spot to generate the elusive Higgs boson—if it exists. Giant detectors five stories high then try to record all the subatomic junk flying out from these collisions.

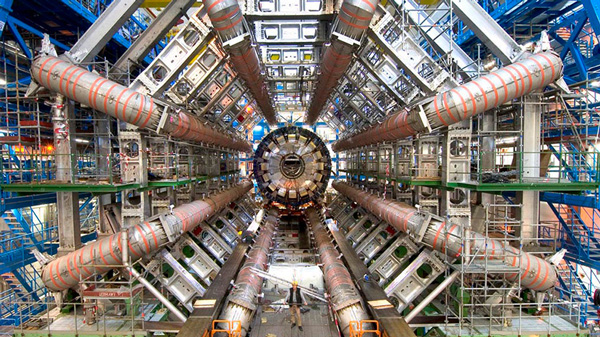

ATLAS is one of the seven particle detector experiments constructed at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a particle collider in Switzerland. ATLAS is 46 metres long (about 150 feet) 25 metres (82 feet) in diameter, and weighs about 7716 tons, making it the largest detector ever built at a particle collider.

When proton beams produced by the Large Hadron Collider interact in the center of the detector, a variety of different particles with a broad range of energies are produced.

Particle detectors must be built to detect particles, their masses, momentum, energies, lifetime, charges, and nuclear spins.

They are designed in layers made up of detectors of different types, each of which is designed to observe specific types of particles.

The various traces that particles leave in each layer of the detector allow for effective particle identification and accurate measurements of energy and momentum.

Photo: courtesy of PF Productions

No one knows what will happen, what will be found. At a minimum they hope to see the Higgs particle (which itself will decay into other particles in a fraction of a second). If it is found, a big question is: What will its mass be? There are two competing theories. Maybe the mass will be relatively low, which is more in line with Standard Model predictions. But then maybe the mass will be much higher, which some scientists think is more compatible with a multiple universe scheme, in which particular physical constants (like the mass of the Higgs boson) are just an accident of the universe we happen to live in.

More exciting still would be the discovery of other new particles, hitherto unknown and unpredicted. A big puzzle for physicists is the existence of "dark matter"—matter whose gravitational effects are seen by astronomers but examples of which have never been found.

Particle Fever builds to a climax around the announcement of first confirmed results about the Higgs particle. There have been two competing teams working with two different particle detectors. Will either or both have evidence of the new particle? And if both do, will they come up with the same value for its mass?

On the big day in July 2012, hundreds of scientists jam the hall to hear the announced results. Others who can't get in are clustered around laptops in adjoining hallways and around the world. The climax of this science thriller is, what else, two PowerPoint presentations on a giant screen!

Both teams have conclusive evidence of a new particle with the predicted characteristics of the Higgs boson. And both come up with the same value for its mass. Peter Higgs, now retired, is in the hall and gets a standing ovation from the audience.

The day was a triumph for science and human understanding of the real world around us. Scientists from over 100 different countries, including ones whose governments are hostile to each other, transcended the vicious divisions of an imperialist-dominated world to expand our knowledge of the universe and uphold the importance of truth.

Edited by Oscar winner Walter Murch, the film is positively beautiful. Oh, and about whether the mass of Higgs boson is high or low, you wouldn't want us to spoil that for you. Go see Particle Fever!

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.