From The Michael Slate Show

Author Lisa Bloom on the Trayvon Martin Case: “People are going to look at this case as the Emmett Till case of the early 21st century”

April 14, 2014 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

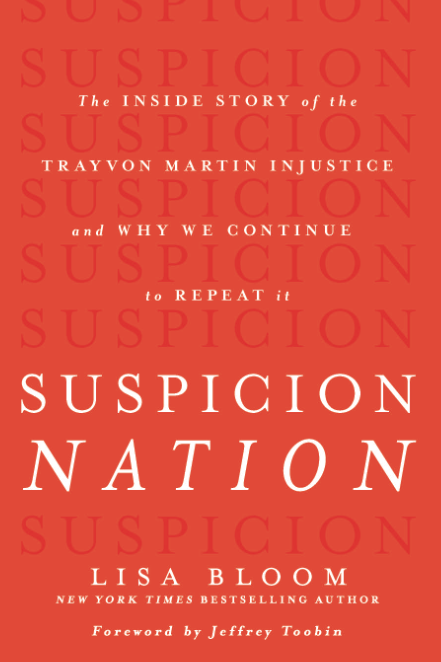

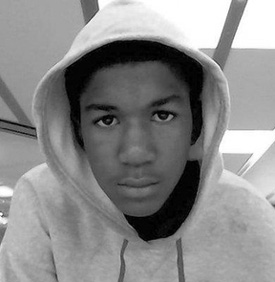

Lisa Bloom is a civil rights attorney, author, and legal analyst on national TV. Her latest book is Suspicion Nation: The Inside Story of the Trayvon Martin Injustice and Why We Continue to Repeat It. Through in-depth investigation, including interviews with key trial participants, Bloom exposes the lies from George Zimmerman’s defense team and the failures of the prosecution. And she addresses what it is about this society that allows so many Trayvon Martins to happen again and again. The following is the transcript of a March 28 interview with Bloom on The Michael Slate Show on KPFK Pacifica radio station.

~~~~~~~~~~

Michael Slate: Going into the case, you thought Zimmerman and his team had all the chips on their side. But after digging into it, you determined that the prosecution actually had a good shot at winning. What changed your mind?

Lisa Bloom: Right. So I’ve been covering trials for so many years, and it’s so interesting that you’re talking about mass incarceration later on in the hour, because that’s a big passion of mine as well. So I know that too many people in America are incarcerated for long prison terms for crimes they didn’t commit. And our criminal justice system has many flaws, but requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt is not one of them. So while it certainly seemed to me that Trayvon Martin, an unarmed teenager walking home, shot and killed, seemed like a terrible injustice, I wanted to see the evidence in the courtroom before I was going to reach any conclusion about George Zimmerman’s guilt.

So I was assigned to cover the case for MSNBC and NBC. I watched every minute of it. And before the trial—I tell this story in the book—I reviewed the evidence. I reviewed the time line, the map of where it happened, the physical evidence, George Zimmerman’s statements. And I thought to myself, well, you know, this is interesting. He tells a plausible self-defense story. He told the story right from the beginning. It’s internally consistent. And he’s really the only witness to talk about what happened. There were a lot of other witnesses, but they saw only bits and pieces, and some of their stories were inconsistent.

So the first week of the trial, I was covering it on air for MSNBC, I noticed a lot of witnesses for the prosecution were not particularly strong, and I thought, you know, this looks like it’s going to be a self-defense case.

But about halfway through, I had my ah-ha moment, and I talk about that in the book. And that’s when I started reviewing the evidence myself, and I noticed there was an absolutely crucial piece of evidence that the prosecution was not arguing. And that is, that George Zimmerman, on videotape, made the day after the shooting, shows that his gun was holstered inside his pants and behind him, over his backside. It was also covered by a shirt and a jacket. Now, that’s extremely important, because his story is, he was down on his back with Trayvon Martin on top of him, knees to elbows. And he says that Trayvon saw the gun, reached for the gun and threatened to kill him. And so at that moment, Zimmerman says, he pulled the gun and shot in self-defense.

Well, unless Trayvon Martin had x-ray vision, there is no way he could have seen the gun in that position. It shocked me to see that on the videotape, and it disturbed me even more that the prosecution wasn’t arguing this. And I started to think to myself, if they’re not arguing this, what else are they not arguing? And so I reviewed the evidence anew, and I discovered a great deal of evidence that they weren’t arguing. I started to talk about this a lot on the air on MSNBC and on the Today Show the last week of trial. I knew this case was going to result in an acquittal, unfortunately, and I said that on the air before the verdict. Because both sides were arguing reasonable doubt. So an acquittal was the only possible outcome. I don’t blame the jury. I blame the professionals in the courtroom.

So after the case was over, like you, I was disgusted. And like millions of people who took to the streets, I was very unhappy. And I was especially unhappy because so many people said, well, you know, the system played out, the jury has spoken, move on. And I wanted to examine what happened. I wanted to interview the witnesses. I wanted to interview the jurors. I wanted to find out what went on, because I think this case was important. I think it was iconic. I think that fifty years from now, people are going to look at this case as the Emmett Till case of the early 21st century. And I wanted to create a record of what went wrong in this case, and what a terrible injustice it was. The investigation I did only made it ten times worse in terms of what I discovered, and that’s all in my book, Suspicion Nation.

Michael Slate: In your book you say that after the trial you were in New York and somebody yelled to you, “Lisa, what happened?” And it struck you that the prosecution blew it. It feels really odd for me to be arguing, “The prosecution should have been harder!” But in something like this—so much was at stake here, on both sides. So much was at stake in terms of; on the one hand, the people had a lot at stake, in terms of really getting to the truth of what happened. And on the other hand, I think some of the various tendencies in the justice system had a stake too, because there was all this stuff that was up: the “stand your ground” rule, the mass incarceration, and what is the position of Black youth in this society? So all that was at stake. But you said that the prosecutors blew it. And you also coupled that with, look; these are not people who just rolled off the turnip truck or whatever. They’re not people who just woke up one morning and said, I’m going to court and prosecuting. These are people who are topnotch prosecutors supposedly.

Lisa Bloom: Yeah. I think a lot of what I do is television commentary where I generally get three minutes to say something. And when the demonstrator yelled out at me, “Hey, Lisa Bloom, what happened?” as this march was going by, I realized that this is not something I can explain in one minute, or in three minutes, or in ten minutes. This is something that requires an exhaustive investigation and a 300-page book. And that’s why I basically stopped everything in my life in the last six months to investigate this and write this book. Because I wanted to explain to everybody who had that gut feeling that something went wrong in this case that you’re right, that we should not just move on. We should expose this injustice. I thought at a minimum that’s something I can do. I’ve been a trial lawyer myself since 1986. I’ve covered every high-profile trial in America for the last 20 years. And this case was different. It was different because the prosecutors bungled the case from start to finish. The police also made terrible mistakes in the case. Trayvon Martin in a very real sense was put on trial, as you say, and Trayvon Martin did not get a fair trial. Not even close.

Michael Slate: You made a point which I found very heavy: there wasn’t even the sort of contestation that needed to be going on, that in fact, on all of the key points, the prosecution ended up conceding and finding unity with the defense.

Lisa Bloom: Right. For example, I go through the big six mistakes that they made, in the book. For example, race. They were afraid to talk about race in the courtroom. And this is a mistake, by the way, that they’ve repeated in the Jordan Davis case, which is why they got a hung jury on the charge of Michael Dunn killing Jordan Davis. Race was very much a factor in the courtroom. The defense very comfortably, if illogically, talked about race in the courtroom. They said that Trayvon Martin was a “match,” that’s their word, “match,” to two African-American criminals, burglars, who’d been in the neighborhood six months prior.

Well the only match was skin color. Trayvon Martin was not a burglar. He was not a criminal. He had no criminal history, no record of violence whatsoever. The prosecution should have been on their feet objecting to this characterization of a dead teenager who was not there to speak for himself. Instead, the jury got the impression that this neighborhood was overrun with Black criminality, when in fact there was not evidence of that whatsoever. There was no evidence that even the criminality in that neighborhood was greater in the 20 percent that was the Black community. So that was just a false impression. That was a racist impression. To attribute the wrongs of two African-Americans, the burglars, to all African-Americans is the very definition of racism. But the prosecution never said so in the courtroom.

Michael Slate: When you talk about race, what you said was true. Race was in the courtroom. It was the big elephant just sitting there. It was sitting there and everyone knew that. There were manifestations of it as you were saying, in terms of the broad, sweeping generalizations, and the characterizations of all Black people as criminals. But even in Zimmerman’s thinking, it’s well-documented that the cat really had a jones about Black people. And there’s all this other stuff that’s going on, and there was also the Rachel Jeantel testimony, which I thought concentrated so much of how much race is at the heart of this.

Lisa Bloom: Probably my favorite chapter, if I can have a favorite chapter in my own book, is where I tell Rachel Jeantel’s story. People will remember she was the 19-year-old, young woman, heavyset woman who testified and was really a figure on social media. People were saying very demeaning, offensive, racist things about her. Others were defending her at the time. But from the point of view of the trial, what was so important was that she had the most important story to tell in the courtroom—because she was on the phone with Trayvon Martin at the time—that he saw Zimmerman; he was afraid of Zimmerman; he was trying to get away from him. When Zimmerman did disappear briefly, Trayvon then went back to joking around with Rachel Jeantel, teasing her about doing her hair. This was very lighthearted conversation he was having with her. This was not a homicidal killer waiting to kill George Zimmerman the way that he described it.

July 14, 2013, New York City. Marching from Union Square to Times Square after the not guilty verdict for the murderer of Trayvon Martin. Photo: AP

Most importantly, Rachel Jeantel says that she overheard the very beginning of the altercation, where Trayvon Martin said, “Why are you following me?” which was a perfectly reasonable question. And George Zimmerman said, “What are you doing around here?” which is an obnoxious thing to say. Then she heard a thump on Trayvon Martin’s chest, where his phone cord was attached, which certainly sounds like Zimmerman assaulting him. And then she heard the sound of wet grass, so Trayvon Martin going down. And then she heard him say, “Get off! Get off!” which is a defensive thing to say. Get off of me. But all of that was lost. Why? Because the prosecution failed to properly prepare her. I talk about how she was sitting alone in a room, waiting to be prepared, how she had a minor speech impediment, an under bite, that has nothing to do with credibility, but that caused her to mumble a little bit and be difficult to hear. That’s the kind of thing that the prosecutor should have brought to the jury’s attention, and should have given them some extra time to prepare her. We trial attorneys have to put people on the stand all the time who are not necessarily the greatest communicators. So what? You prepare them. You go over the testimony. You give them the practice questions. You give them some practice cross-examination. It’s absolutely outrageous that they didn’t do that with Rachel Jeantel. And that’s probably one of the biggest reasons why they lost the case.

Michael Slate: The Rachel Jeantel case—I also was really moved by that chapter. Because this young woman went through so much hell. Just to begin with, her very close friend is murdered. And then she’s accused of lying, and covering her tracks. As if she did something wrong. But it’s all couched in this thing—even the assault on her for “We can’t understand what she’s saying,” because she’s speaking Black English! Just a massive amount of an assault against her. And I was really moved by that. But I also thought your point about the preparation, I have to tell you, Lisa, there were a number of times in your book that I had to sit back and say, “Damn! Next time I’m arrested, I want Lisa as my lawyer.”

Lisa Bloom: [Laughing] Well, thank you. I’ll be there for you, Michael.

Michael Slate: The thing is, I’m reading this, and all the points you make about the preparation, and then you say, here’s how you should have done it. Why do you think that this preparation—again, these are not bumpkins. Why do you think they didn’t do that preparation?

Lisa Bloom: Well, thank you for the compliment, and I do like to think I’m a good lawyer. I do practice law. But honestly, the things that I’m pointing out in the book are “Lawyering 101.” Like preparing a witness, please, this does not take twenty years of practicing law to put together, that you have to prepare your witnesses. And you’re right, Bernie de la Rionda, who was the lead prosecutor, bragged that he had won 80 out of 81 cases before this trial. So he certainly knew how to win a case.

I think what you’re asking ultimately is what I call the “Blow it, or throw it” question. Did they blow the case? Or did they intentionally throw the case? And I’ve had a number of readers of my book actually argue with me based on what they read in my book, and they feel adamantly that the prosecution intentionally threw the case. I myself am not going to come to that conclusion unless I have some hard evidence. I think it’s hard to have a conspiracy with a lot of different people, and nobody reveals it, so I’m not going there. I will say there are a few facts that indicate that they threw it. Those facts are that Angela Corey right after the verdict, right in front of the cameras, had a big smile, and she said, “The system worked. I think the police are vindicated by the acquittal.”—the police these prosecutors have to work with every day. I have the medical examiner in the book who said that behind the scenes, none of them, none of the prosecutors or the police thought that Trayvon Martin was truly a victim.

But overall, in a sense it’s almost worse than that. And that is that they just didn’t put the effort in this case to win it. This was a case that was foisted upon them by the public. Remember, for 45 days, they didn’t even arrest George Zimmerman. It took protests all across the country for that arrest to happen. I think they just didn’t care. They just didn’t believe in their case. And ultimately, when it was assigned to them, they just did a perfunctory job. They just put the evidence on, but without connecting the dots, without really connecting the facts and the law, doing a strong closing argument. The closing argument was a disaster. I think their heart was just not in the case.

Harlem, New York City, July 2, 2013, March against the verdict in Trayvon Martin's case. Photo: Special to Revolution

Michael Slate: I want to get into the closing argument in a little bit, but I did want to ask you one question, because one of the things, and I know I’m not going to dig into all the mind-numbing and actually astounding exposure that you do around what was actually possible to present, and didn’t get presented. But there was one thing that really struck me, and that was the forensic evidence, and the complete disregard for any of that, taking any of that on, and in particular, the idea related to the infamous call, the Lauer call, the call where they actually had somebody screaming on there, and it was finally determined that, well, we can’t really determine who it was, but it was really closely linked to—you had a thousand people saying, “Oh, no, that was George Zimmerman screaming,” and three people saying that it was Trayvon screaming. And there was no attempt to even dissect that. And you bring out that it was actually more than possible to get really close to thinking that it was Trayvon, if not proving that it was Trayvon screaming

Lisa Bloom: Well, a couple of things. First of all, Rachel Jeantel said that Trayvon Martin had a high-pitched voice, “a baby voice,” she said at one point in relation to something else. But the man screaming on that 9-1-1 call just before the gunfire rings out has a high-pitched voice. The prosecution never connected that for the jury. We know that George Zimmerman did not have a high-pitched voice, because we heard him on several audio recordings in the courtroom, even though he didn’t testify.

And what you’re talking about is a scientific theory called pneumothorax that one of the expert witnesses wanted to present for the prosecution, that would have shown that the moment that the bullet went into Trayvon’s body, there were two fragments that punctured his lung and caused this condition called pneumothorax that would have prevented him from breathing and speaking, and making any sound immediately. Well, that’s a perfect match to the fact that on the 911 call, as soon as the gunfire rings out, the screaming stops. So it would tend to make more likely the fact that it was Trayvon Martin screaming for help.

I put together my own theory in the book based on all the evidence, what I think happened. I think Zimmerman pulled the gun out early in the altercation because he was afraid of Trayvon Martin, and he wanted to control him. And I think Trayvon Martin was screaming horribly, poignantly for about 40 seconds because there was a madman pointing a gun at him, and he was scared for his life. He turned out to be right.

Michael Slate: Absolutely. I really agree with you. Let’s talk about the closing argument, because once again, Lisa, I don’t ever cheer for prosecutors, okay? But when you developed your own closing argument, what could have been and what should have been, I was like, “Yes! Yes! Nail him!” But the thing is that you really did show this, that these guys again, they were conceding everything. And at the end of it, they didn’t argue anything. And you said that they abrogated their responsibility to give the jurors a road map to conviction. And I thought that was really important. They never explained the charges. All of these things. Can you talk to people about the closing argument? It really did concentrate what went on during the trial.

Lisa Bloom: One of the things I felt that I could offer by writing this book is the way these cases usually go—because a lot of people watched this case, but they’re not necessarily familiar with criminal trials, or with murder trials. The prosecution in this case never offered its own theory of the case. They never offered their own story as to what they thought happened just before Trayvon Martin was shot. And the defense always had their story. George Zimmerman said he shot in self-defense. He said that there was an altercation, that he was down, that Trayvon Martin was on top of him and he shot in self-defense.

Well, the prosecution needed to counter that. And I was shocked that they never did. They essentially went with the defense’s version of the case and they just argued details around the edges. And it was always clear to me that if this jury believes that Zimmerman is down on his back, Trayvon Martin is on top of him, he’s threatening to kill him, he’s hitting his head on the concrete as Zimmerman said, he’s threatening to shoot him, well of course, the jury is going to acquit him, because that’s a very scary story, and frankly, we all have the right to kill in self-defense if our lives are being threatened.

I have never seen a murder trial, and I have seen hundreds and hundreds of them—for eight years, I hosted a show on Court TV, and almost all we did was watch murder trials [Laughing]—I have never seen a case where the prosecution did not offer its own theory of the case. The jury will simply not do that job for the prosecution. And they didn’t do it here. What they did do in closing argument was ask a lot of questions. That was very odd. You know: why did you think this happened? Why did you think that happened? You can put this together. You don’t ask the jury to go into the jury room and put it together themselves. You give them a road map to conviction. You put up the law. You emphasize the parts of the law that are helpful to you, that are important, and you plug in the evidence to the law to show how your side is going to win the case, to show them why they should convict.

And the prosecution just did not do that. They just asked a series of questions. It was a rambling, disjointed presentation. I have some of the choice quotes in the book. I mean, I was really astounded. They had some passion. They had some quips. And people who watched the trial with me who aren’t trial lawyers said, “Oh, I thought that was very moving.”

You know, it’s not enough in closing argument to just have some rhetoric and some passion. You have to put it together for the jury. I have the story inside the jury of how they took it, which was, yeah, there was a lot of passion, but we were told to decide the case based on the evidence, so we had to put that aside. One of them said, “All they gave me was passion, and they said don’t decide the case based on that, well that jacked me up.” I think that did jack them up.

I also think the prosecution should have known better. They had to have known better.

Michael Slate: I’m going to read something from the book. It’s very short, but I think it’s really important in terms of entering into this new section of the book. And it starts with, “Please use my story, please use my tragedy, please use my broken heart to say to yourself, we cannot let this happen to anybody else’s child.” And that’s from Sabrina Fulton, Trayvon Martin’s mother. Now you go on and you say, “Trayvon Martin’s death was not a tragic accident, unforeseeable, unstoppable as though an asteroid had smashed into the earth without warning, taking a life. Human-made stereotypes and laws created all the conditions that led to the death of Sabrina Fulton’s son, and that made George Zimmerman’s acquittal by far the most likely outcome.”

Let’s talk about that, because I think it’s really important the way you actually, after presenting this very, very powerful analysis of the case and what was going on, you also then say, but we have to step back because as much as we don’t want there to be, there’s going to be more Trayvon Martins. And we’ve seen it. We have a lot of examples, whether it’s this young woman, Renisha McBride, who was shot when she was seeking help after a car accident near Detroit, Jordan Davis, what just happened there. There’s all of this stuff that’s going on, and you point out that this is rooted in the fabric of society, the way the culture, the fabric, the things that are being done that lead to this kind of situation, the mass incarceration, the slow genocide that’s being unleashed against particularly Black people.

Lisa Bloom: Yes. So the second half of my book is a deep dive into these conditions, because I’m tired of everyone being shocked and appalled each time one of these cases happens. Of course, they are shocking, and they are appalling. But until we dig down into the root causes and get some change, they’re going to continue to happen.

So the three biggest factors that were at play here, and that have been at play in a number of cases are rampant racial profiling in America, our lax gun laws, and “stand your ground.” Those are the three factors. The first, racial profiling, we can make some legal changes, but that’s really a cultural change we have to make. And so I talk a lot about implicit racial bias, which I think is a really important concept that frankly, I learned about while I was covering the case and trying to figure out, how is it in America, nobody admits to being racist, and yet there are so many racially disparate outcomes. If you ask a group of people, hey, who in this room is a racist? No one’s going to raise their hand. Everybody considers it a vile insult, which it is.

And yet in our criminal justice system, for example, a Black man is four times as likely to be arrested and incarcerated for marijuana possession as a white man. Black youth are more likely to be sentenced to longer terms than white youth who are being sentenced for the same crime. Especially in our criminal justice system, from beginning to end, from arrest through conviction, through sentencing, through parole—there’s no question that everything is worse for African-Americans. There’s no question that there’s a huge advantage to showing up with white skin. And yet this is a system in which most of the participants, I think, are good people. They’re people who would say, well I’m certainly not racist. And many of them are African-American or Latino themselves. So how do we have this problem? And I think the answer is implicit racial bias.

For those who aren’t familiar with implicit racial bias, there’s a test you can take online for free. I have the citation in my book. I took the test myself. It turns out that 80 percent of white Americans test for moderate or severe implicit racial bias against Blacks. And 50 percent of Blacks do as well, which is very disturbing. This is a test that you take, you can’t cheat, you can’t trick, and it tests for whether you have these biases subliminally. And it’s really an eye-opener that we see African-Americans differently. There’s so many studies, for example, a Black face and a white face that are in a sort of identical facial expressions, and people overwhelmingly say the Black face is more hostile. They take a young Black man and they have him shove a white man on a video, and something like two thirds of the subjects say that’s an aggressive act. But when it’s flipped, a white man shoving a Black man, only 17 percent say that’s an aggressive act. Most people say, oh, they were just horsing around.

So there’s no question that in the way that we perceive African-Americans, we see them as more hostile, we see them as more aggressive. This plays out in our educational system because African-American boys in particular are more likely to be suspended or expelled, just at skyrocketing numbers. And it plays out in our criminal justice system. And until we address this root problem we’re never going to advance,

Michael Slate: Can we talk a little about the “stand your ground” rule. Because it wasn’t invoked in the Zimmerman case, does not mean that it’s somehow disappearing, or that it’s not as intense and oppressive as it actually is. Let’s talk about that.

Lisa Bloom: “Stand your ground” was very confusing in the Zimmerman case. First of all, it was part of the reason why he wasn’t arrested for those 45 days, because of “stand your ground,” because the police thought he had the right to “stand your ground.” Then he was arrested. He had the right to a pre-trial “stand your ground” hearing that would have exonerated him, potentially. He chose not to have that hearing. He went to trial in front of the jury. Nobody argued “stand your ground” in the trial, except in closing argument it was mentioned briefly.

But then “stand your ground” came in as part of the standard self-defense jury instruction. The judge read to the jury that George Zimmerman had the right to stand his ground. And the jurors said afterward as part of their decision-making process that they thought that George Zimmerman had the right to stand his ground. So anybody who says that “stand your ground” was not part of the Zimmerman case is not familiar with these details, which are not really not details, because these were pivotal parts of the jury’s decision making.

Michael Slate: Okay—Lisa—thank you very much.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.