Interview with Educator and Oral Historian Timuel Black

Remembering the Lynching and Funeral of Emmett Till: “I was ANGRY!”

September 7, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Timuel Black, 96, is an eminent educator, political activist, and oral historian. He has taught at a number of high schools, as well as universities, in Chicago. He is perhaps best known for his series of books, Bridges of Memory, about the Great Migration of Black people from the South and about Black Chicago history from the 1920s to the present.

He graciously agreed to be interviewed by Revolution newspaper about his experiences at the time of the Emmett Till lynching and funeral in 1955. He started by getting into “the background and context that led to the accusation that Emmett Till had insulted this white lady,” by way of his own personal experience going from north to south as a soldier during World War 2.

Revolution Interview:

A special feature of Revolution to acquaint our readers with the views of

significant figures in art, theater, music and literature, science, sports and politics. The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our paper.

Professor Black told us about his experience in the South more than a decade before Emmett Till was killed:

When we were drafted into the army in World War 2, those up in the North were sent south to get our so-called basic training. I was in Camp Lee near Petersburg, Virginia. There was a Black college there, so we would go and visit on breaks. But if we went into town with our soldier suit on, we had to learn that whoever was Caucasian could come and get in front of us... even though we were supposed to be back in camp at a certain time. If we got on the bus, or any other transportation, and didn’t remember that we were Negro, and just sat down, we might be beat up, or certainly be told that we had to go to the back of the bus. We were not accustomed to that. Like me, most of our families had fled the South during the first great migration to be rid of the Ku Klux Klan terror being applied back there. People like my daddy were in jeopardy all the time. My mother was so glad they fled the South. They were kind of drafted to come north by Black newspapers, but also by the growing industries—steel mills, stockyards.

What I’m trying to get you to understand is the background and context that led to the accusation that Emmett Till had insulted this white lady. Emmett Till was from the North. So those of us who were in service... for example, because I was so unsophisticated, I got word that my unit was being shipped overseas. I wasn’t even thinking, but I wanted my brother to know that I was going overseas, and I wanted my mother to know, so I jumped on a bus. I had my uniform on. I was the first person on the bus, I just sat down, as I would do in Chicago. So just after that a white guy gets on the bus with a white woman. Immediately he goes to the bus driver. I had made up my psychological and emotional mind. The bus driver comes, “You’re sitting in the wrong spot.” I asked, as if I didn’t know, “Why didn’t you tell me that when I got on? You mean to tell me to sit in the back and I’m about to go overseas and lose my life? Hell NO!” I was prepared to die, psychologically and emotionally. Fortunately, we got to the train station and I had cooled myself and knew how to behave.

My attitude was, “Why go overseas and die when I can come down here and die?” That’s an experiential culture that those of us from the North carry with us. We tried to adjust, but sometimes it was very difficult. We go overseas in a segregated army; I’m smarter than my commanding officer, by their own standards, but he has to keep me in my place. I had to adjust and stay in my place, as my momma had commanded. This is not just Tim Black, this is also Emmett Till not knowing how to behave in the South.

We asked Timuel Black to talk about going to Emmett Till’s funeral:

Now when Emmett was killed, drowned, and they had the trial... it was so unfair. Because these men who were accused were acquitted without much of a problem. They later in a national magazine admitted that they had done it. Now when some of my students—I was teaching at Gary, Indiana, Roosevelt High School, but I still lived in Chicago―a lot of those students had lived in Mississippi. When they heard the story of Emmett Till, they knew, and immediately they wanted to go back home to fight that battle.

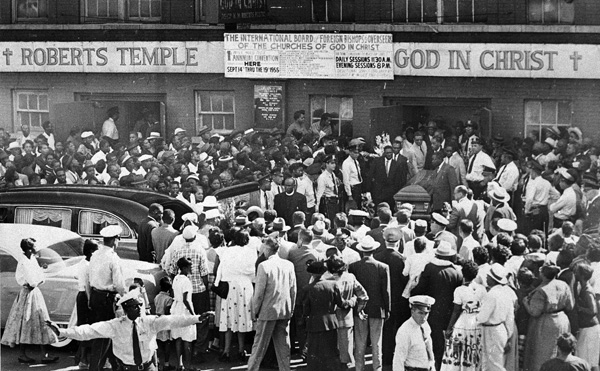

The undertaker was A. A. Rayner, longtime friend of my family. The lines outside of the Rayner Funeral Home, on 71st street, were two and three blocks long, on a continuous basis. Mr. Rayner was preparing Emmett’s body for the funeral. The participation in the funeral [at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ], in terms of numbers, was very similar—it was over-packed, and lines were outside. Emmett’s mother had decided that her son, and the condition of her son when he was finally pulled from the water, would be available for everyone.

Even if they couldn’t hear the minister, they were weavin’ and grievin’, because, as they could say, no one in those lines had not had a similar experience in their own family. Personal grievance and experience, transferred to the drama of Emmett Till. That was a great day in history, in African-American history, that most people don’t know about. But I hope your project can give some attention to that.

We asked whether he was able to go inside the church at Emmett Till's funeral and view the open casket.

Timuel Black: I was there. I was inside.

Revolution: And what was your emotional reaction?

Timuel Black: I was ANGRY! I was angry. I don’t know if I was sorry, but I was angry. And my attitude was: “We’ve got to get rid of these motherfuckers.” That was my street, personal attitude—we’ve got to get rid of this shit. But there were many others who felt that way, I’m just articulating one guy’s expression of a community’s spirituality about an injustice that had started during slavery. The stories of men being castrated and women having hot pokers placed up their vaginas when they broke the culture. And the public spectacle, with the children, for both sides to see. For the Blacks: “See, this will happen to you.” And the whites: “This is what you’ve gotta do.”

So that division, which existed so openly then, carries forward now, in a much more subtle way. The police, conditioned against young Blacks, particularly.

Professor Black concluded by talking about the historical significance of the lynching of Emmett Till:

So the day of Emmett Till then made it easier, when in that same period, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks and E. D. Nixon planned that she would get on the bus, and not give up. The funeral of Emmett Till spurred the movement, but it didn’t start it. We who were present at the funeral could understand it, and we carried the life of Emmett Till that we had experienced into expanding the civil rights movement, which became more national and international. And the reverence of Emmett’s family at the funeral, that diversity, primarily African-American, but Caucasian as well, spurred the feeling that things must change, embodying the idea in the song by Sam Cook, “A Change Is Gonna Come.” Emmett Till dramatized and spurred the civil rights movement during that period and later.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.