Interview with Environmental Professor Dr. Stuart Batterman

"A Double or Triple Whammy"

February 22, 2016 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Stuart Batterman, Ph.D. is a professor of Environmental Health Sciences at the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan. In light of the situation in Flint, Michigan, where close to 100,000 people have been exposed to lead poisoning through the water system, revcom.us/Revolution talked with Dr. Batterman about the situation in Flint and the larger problem of lead poisoning in the United States. The following are excerpts from the interview:

Revolution: Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician who tested children in Flint, said, “If you were to put something in a population to keep them down for generations and generations to come, it would be lead.” Maybe you could comment on this statement.

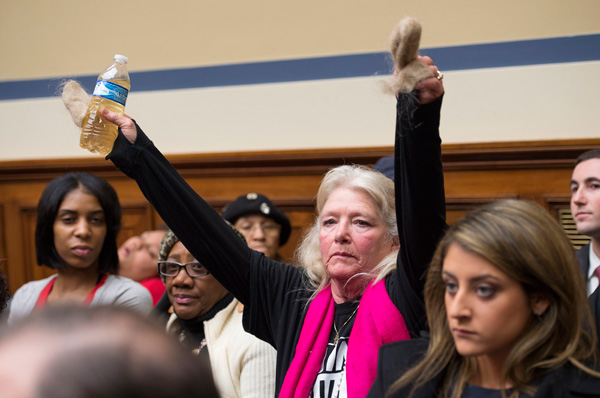

Flint, Michigan residents on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C., at a House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing about the water in Flint, February 3. This woman is holding a bottle of tap water in one hand, and hair from the drain in her shower in the other. (AP photo)

Stuart Batterman: What happened in Flint is a tragedy because you’re taking a bunch of people, not just kids but also adults, and exposing them to something that’s entirely preventable and something that can have lifelong effects. And with lead we see intergenerational effects. So these children, depending on the level of exposure they may have had, may have health effects, and their children may have health effects too. The possibility of an intergenerational element compounds the tragedy.

One additional thing that’s important to add, not to diminish what has happened in Flint, is that there are about half a million children elsewhere in this country that currently have lead levels above the guideline values. In Detroit, Michigan, for example, 50 miles from Flint, there are areas where 20 percent of the children have lead levels above the guideline. Moreover, we’d like to lower the guideline values.

At the [recent] hearing [in Washington DC on Flint]. I think it was Representative Cummings from Maryland that stated if this had happened in a rich suburb of any other city it probably wouldn’t have happened. Unfortunately, we see environmental justice issues in many contexts. For example, I deal with air pollution problems in Detroit. Typically the worst pollution problems are affecting minority communities, the poorest sectors, folks who have poor job security, and little access to preventative health care. And then they have pollution to deal with. So we see rates of environmentally-related diseases that are higher and sometimes much higher than of the general population. We consider these individuals to be vulnerable and susceptible to environmental pollutants.

Revolution: So is it kind of like a situation where, like let’s say in Detroit, everybody is getting the pollutants in the air, or like in Flint everybody is getting the lead in the water. But certain sections of the population because of other vulnerabilities, are disproportionately affected.

Stuart Batterman: I’m saying it kind of works like a double or a triple whammy. So not only do they get the pollution, but they are also more susceptible to pollution because they may have a bad diet, less preventative health care, and often they have pre-existing diseases. And then when they get sick they don’t have access to good health care services or health management. For example, they may not be able to take steps to reduce high blood pressure or to manage their asthma appropriately.

In Flint, I think that the emergency city manager was trying to save money. I think that the state agencies charged with enforcing the environmental laws are not typically oriented to deal with emergencies. They have a review function and competent people. But they often are cautious, and it can be difficult to flag problems at an early stage.

You know, if you go back some decades, you might ask, well why do we even have lead pipes? Why were they allowed? For many years, the Lead Industry Association said they’re the best thing. This is the lobbying and political arm of the lead industry. And there were substitutes available. But the industry exerted pressure and argued very effectively, and so many cities were still using lead pipes until the ’60s and ’70s and even later.

Revolution: Even after it was known this was harmful?

Stuart Batterman: The medical and scientific community has known that lead exposure is harmful for over 100 years. The Romans, I think, were the first to use lead pipes—they used a lot of lead. In the modern era, we have medical reports that people died from lead exposure back in the 1890s, and by 1920 or so scientists and others were concerned, but there was no federal regulation on lead pipes until the Clean Water Act amendments in the mid-1980s.

Revolution: I also know that when they were trying to get rid of the lead in gasoline that there was a huge lobby effort to stop this by the gas companies.

Stuart Batterman: Right. The gasoline companies and the auto companies were basically forced to remove lead in gasoline in the 1970s, not because of the environmental impacts of lead but because we wanted to add catalytic converters to cars. The catalytic converters, which reduce air pollution, would be poisoned by lead.

In hindsight, there was a happy combination of circumstances since we got rid of other air pollutants plus lead. And the amount of lead used in gasoline was huge, about 200,000 tons a year of tetraethyl lead as a gasoline fuel additive. By the way, aviation gas, the fuel used in smaller planes, and gasoline for farm equipment—still contain lead.

Revolution: What does that mean? That there is still lead pollution coming from that?

Stuart Batterman: Right, so around airports, especially where there is a lot of civil aviation, you can pick up a lead signature in the air. It’s not a very high level, but you can detect it.

Now, even though we’re not using lead in gasoline and even though we’re not using lead in most paints, the soils that are in urban areas can have a lot of lead. The level is predominantly from those two sources—from lead in paint that’s chipped off and from gasoline because the lead eventually comes to the ground. In addition, we also used to have many lead smelters. And so whenever that soil gets kicked up in a windstorm or whatever—it often happens in summertime when the soils dry out, we see levels of lead going up a bit in air and blood as well.

Revolution: Are there any efforts to address this? I mean this is a huge problem.

Stuart Batterman: Well, yes and no. If you have a child who is lead exposed based on a blood test, then we should try to follow up and identify the sources of lead and then remove them from that child’s environment. The programs that do this have been cut back by Congress in the last few years. If lead levels in soils are very high, sites can be designated as a Superfund site. This was done just outside of St. Louis, Missouri, in a town called Herculaneum, the home of one of the larger lead smelters in the country called Doe Run. Up to just a few years ago, this facility continued to emit lead, and sometimes it exceeded or nearly exceeded the air quality standard for lead. Over the course of its operation, some 40 years or so, soil was contaminated across a large part of the city. And parts of this city were designated as a Superfund site.

The remedy was to have topsoil replaced and other actions to remove the lead. That’s an extreme case. But there are many sites of former smelters in many older cities across the country. In part, this is because a large amount of the lead that’s used is recycled lead and you get that by melting it down and recasting it. And so cities like Detroit; Cleveland; Camden, New Jersey; Philadelphia; Boston; others; they all have a share of sites that are lead contaminated because of the history of old smelters. Unless cleaned up, once in the soil, lead just stays there.

Revolution: So Flint really is just the tip of the iceberg.

The views expressed by those we interview are, of course, their own; and they are not responsible for the views published elsewhere in our newspaper/website.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.