Revolution #260, February 19, 2012

Voice of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

Please note: this page is intended for quick printing of the entire

issue. Some of the links may not work when clicked, and some images may be missing.

Please go to the article's permalink if you require working links and images.

Revolution #260, February 19, 2012

- The Cultural Revolution in China...Art and Culture...Dissent and Ferment...and Carrying Forward

the Revolution Toward Communism

by Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

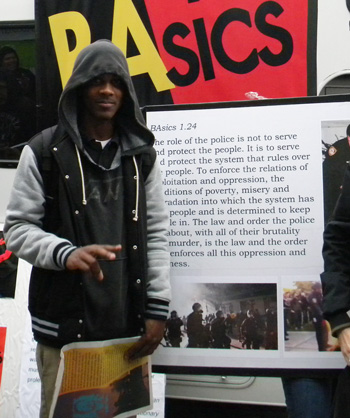

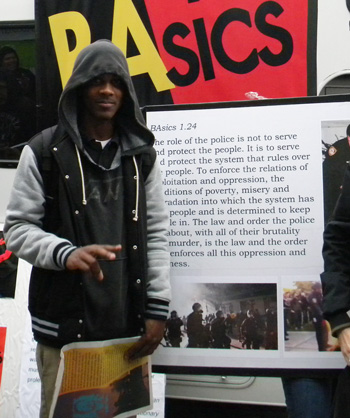

- BA Everywhere—Imagine the Difference It Could Make

- The Outrageous NYPD Murder of Ramarley Graham

- Urgent Situation at Corcoran: Reports of the Death of a Prisoner Hunger Striker

- Ask a Communist

There Are 2.4 Million People in Prison in the U.S.—Why? What Do We DO About It? And How Does the Notion of a "Prison-Industrial Complex" Get This Wrong?

- “Stand With the Occupy Movement!”: Support Grows for February 28 Mass Action

- Letter From Andy Zee: OCCUPY & the Way Forward NOW

- End Pornography and Patriarchy: The Enslavement and Degradation of Women!

Abortion On Demand and Without Apology!

Fight for the Emancipation of Women All Over the World!

- Saturday, March 10

Celebrate International Women's Day

12:00 Noon - Protest and March, New York City

- A Talk by Carl Dix

Mass Incarceration + Silence = Genocide!

Mass Incarceration — Its Source, The Need to Resist Where Things Are Heading and The Revolution We Need!

- A Challenge from Raymond Lotta to Slavoj Žižek: Let’s Debate the Nature of Imperialism, Prospects for Revolution, and the Meaning of the Communist Project

- It is right to want state power. It is necessary to want state power. State power is a good thing—state power is a great thing—in the hands of the right people, the right class, in the service of the right things: bringing about an end to exploitation, oppression, and social inequality and bringing into being a world, a communist world, in which human beings can flourish in new and greater ways than ever before.

Bob Avakian,

Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

BAsics 2:10

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/260/avakian-on-cultural-revolution-in-china-en.html

Revolution #260 February 19, 2012

The Cultural Revolution in China...Art and Culture... Dissent and Ferment...and Carrying Forward

the Revolution Toward Communism

by Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

May 9, 2016, originally published February 19, 2012 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Editors’ Note: In this issue we are reprinting part of an interview with Bob Avakian, this one conducted in 2004. It originally aired on Michael Slate’s Beneath the Surface show on KPFK radio in Los Angeles, on July 29, 2005. In publishing it here, some editing has been done, particularly for clarity. In some places brief explanatory passages have been added within brackets. Subheads have also been added.

MS: Let’s dig into the Cultural Revolution [in China, from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s]. You led communists around the world in fighting to understand what the significance of the Cultural Revolution was, and to uphold it as a dividing line question, and to see it as the highest point of class struggle in human history, the greatest height the class struggle’s gotten to in human history. That’s not exactly—in terms of conventional wisdom today, that’s not exactly what you find on the bookstore shelf. You can find 70 books about how—and you can hear people who are 32 years old talking about how—the Cultural Revolution destroyed their careers, and they had remarkable careers when they were like two years old. But it’s had an impact on people. It’s had a big impact on people.

You had musicians who once were major supporters of the Cultural Revolution who now listen to these stories from people, from artists coming out of China, for instance, and saying, “I was misled. I didn’t understand everything that went on because I didn’t understand the suffering that people have.” Or you have these popular cultural forms, The Red Violin, for god’s sake: a movie that had nothing to do with China, but there was this one scene in it where they had to show the Red Guards banging down doors and pulling people out of their houses, searching for this red violin that they needed to smash. And it was this symbol of artistic freedom and creativity.

Or you had Farewell My Concubine, which was a big, big movie among—I know a lot of my friends, a lot of artists and intellectuals who went to see that film two, three times, and really looked at it as a sign of what was wrong, and how the Cultural Revolution was not an advance for humanity, but something that was actually part of suppression, and particularly suppression of intellectuals and artists.

I wanted to ask you about that—let’s talk a little about the question of intellectual freedom. And I think it’s tied up with the question of dissent, but we can get into that separately. But I think actually this idea of—what you’ve been saying all along, and one of the reasons I asked you about this question about the Party and everything else in terms of people starting to settle in, and that kind of thing—is that you had talked earlier about the need for really just a totally, tremendously creative surge among the people and in the Party and among communists, this constant creative application, and then that Marxism itself is a science that actually, in a living form, really does do that. When you were saying that, I was just thinking, you know, it’s so refreshing to hear this thing because it invigorates you with a sense of like, you know, [what] our science really is—it unleashes the greatest creativity, when you grasp it, it unleashes the greatest creativity possible.

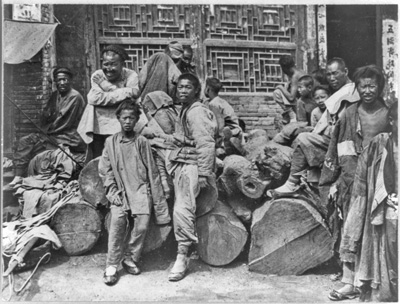

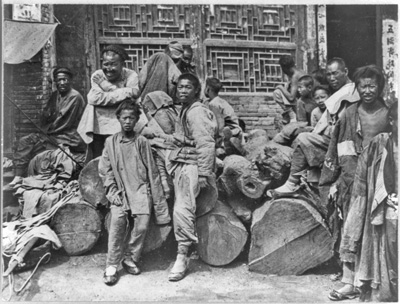

Street scene in China before the revolution

But there’s this common, or this conventional wisdom that actually—here’s this crucial development in the class struggle, this crucial development of the science of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, and yet it’s portrayed as this sort of thing that was the suppression of artistic and intellectual freedom.

BA: Well, once again, I hate to sound like a broken record, but this is a complex question and a complex problem that the Cultural Revolution was seeking to address, and was addressing. And once more you have to situate this in what was occurring in the development of the Chinese Revolution, and not come at it from the way all too many people do in this society. They don’t understand the actual dynamics—why these revolutions were necessary in the first place, what they arose out of, and what were the contradictions they faced when they emerged. And some people have some sense of, OK in China people were poor. If you have read those Pearl Buck novels, you know, people of our generation, where you get a sense about the terrible life of the peasants, and you can understand why people would want to cast off that oppression, and so on. But a lot of people are even ignorant of that, especially now. They have no real sense of what China was like, and why a revolution was needed, and how that revolution had to take place.

Foot binding was the custom of breaking the arch of the foot and the toes of a young girl (between the ages of two and six) and then binding each foot painfully tight to prevent further growth. This was practiced mainly among the wealthier classes. The tiny narrow feet were considered beautiful and to make a woman's movements more feminine and dainty.

Bound feet rendered women dependent on their families, particularly the men in their families. When the revolution succeeded in 1949 and the new society was established, foot binding was outlawed as a step towards liberating women.

So that’s one problem. But not only did they have to overcome the whole daunting prospect, or reality rather, of imperialist domination and carving up China, but they also had a whole history of feudalism, of massive exploitation of the peasantry and hundreds of years—or thousands of years, actually—in which the great majority of people were just desperately impoverished and exploited. And they were coming from a society which, because it was dominated by imperialism, and because of the remaining feudalism, was not advanced technologically, or was technologically advanced [only] in a few enclaves. But then the vast part of the country and the people who lived in it were mired in a lot of enforced backwardness.

So you’re coming from that, and you’re trying to make leaps in terms of overcoming the poverty and the oppression of the masses of people. And you come to power, in 1949, and right away, within a year, you’re thrust into a war with the U.S. in Korea—a war in which MacArthur is saying: let’s take the war to China. That was his big dispute with Truman. Let’s take the war to China. Let’s go right to China and cross the border. Not just go near the border, but go across the border, and roll back the Chinese revolution.1

And so right away, you barely have time to celebrate and consolidate your victory, and you’re thrust into this battle with this powerful imperialist force right at your doorstep, literally. And then you fight the U.S. to a standstill, and in effect defeat it—because, in terms of its objectives in Korea, once the U.S. entered the war, they were thwarted in those, in large part because of the involvement of the Chinese in that [war].

So here you are. Now you’re trying to take this country that’s poor and backward, has been dominated by imperialism—you have the situation where [there was] the famous sign in a park in Shanghai, “No dogs or Chinese allowed.” This is just a stark way of expressing what their life was like, even in the urban areas, even if you were among the more educated classes, for example. So what you were referring to earlier—a lot of people did either go back to China [after the victory of the revolution in 1949], or a lot of people in China, intellectuals and others, were very enthusiastic about the new society that was being brought into being, because it was going to overcome this whole situation where China was held down and carved up by different imperialists and the Chinese people and the Chinese nation was going to be able to stand up on its feet and not be run roughshod over and lorded over by these foreign powers, and so on.

Contradictions, and Challenges, of the Socialist Road in China

But within that there’s also a contradiction, that a lot of people are—it’s sort of captured in Mao’s thing that “Only socialism can save China.” What I’m trying to get at—this is a contradictory statement actually, because he’s saying that without taking the socialist road, China cannot get out from underneath the poverty and the domination by imperialism, and so that’s the only road for China. Which means that a lot of people—the reason I say it’s contradictory is it means a lot of people who were not really won to the communist vision will support the revolution and will even support going on the socialist road because it is true that objectively there’s no other way that the backwardness and domination by imperialism can be ended.

On the one side, there’s obviously a positive aspect to that. You get a lot of people, including in the more bourgeois strata, who are enthusiastic about the socialist road because it does represent the way out for China. But, on the other side of it, they’re coming at it from more like a nationalist point of view, or a more bourgeois point of view. They want China to take its rightful place in the world—and they don’t want it to be stepped on by foreigners, and so on—which is certainly legitimate, and something you can unite with. But it’s contradictory.

And that phenomenon existed, not only outside the Party, but to a very large degree inside the Party in China. A lot of people joined the Communist Party in China for those kinds of reasons. And they had not necessarily become fully, ideologically communists in their outlook, and really being guided by the whole idea of getting to a communist world—and internationalism, of doing it as part of the whole world revolution and sacrificing for that world revolution when necessary—but more from the point of view: this is the only way China can stand on its feet and take its rightful place in the world. Well, a lot of those people were in the Party for a long time. A lot of them were veterans of the Long March and made heroic sacrifices, but never really ruptured completely to the communist viewpoint, which certainly encompasses the idea that China should throw off foreign domination and the poverty and backwardness of the countryside and feudalism, but is much more than that, and it goes way beyond that.

So this is one of the problems, the contradictions that were existing within and characterizing the struggle within the Chinese Communist Party right from the beginning. And then there’s a whole other dimension to it, which is that everybody has the birthmarks of the womb they emerge out of, so to speak. And that was true of China in terms of the world and of the Chinese Revolution. The new society emerged out of the old one in China, and carried the birthmarks of that, the inequalities and so on.

Breaking With, Going Beyond the Soviet Model

BA continues: But it was true in another important dimension, too, which is that the Chinese Revolution was made as part of the international communist movement, in which the Soviet Union was the model of how you made revolution and how you build socialism. Well, it’s interesting—here’s another contradiction: Mao broke with part of that. In order to make the revolution in China, they had to break with the Soviet model, which was the idea that you centered in the cities, based in the working class, and took power in the cities and then you spread it to the countryside.

The Chinese approach to it that Mao forged, after a lot of defeats and some serious setbacks and bloodshed and bloodbaths that they suffered trying to do it in the cities and being crushed by the forces of the central government, or Chiang Kai-shek’s forces,2 was to finally do it the opposite way—to say we have to come from the countryside: because it’s a backward country, we can start up guerrilla war in the countryside, where most of the people live, and advance to finally taking the cities. So that was the opposite of how they did it in Russia. Now, it’s true that in Russia the majority of people lived in the countryside, but it was a different kind of society than China. And they didn’t really have the possibility of waging guerrilla warfare from the countryside in Russia the same way that they did in China. So right there, Mao had to break with the Soviet model and forge a new model of how you make revolution in China and in countries more generally like China.

But then, when they got to actually—OK, here we are, we’re in power, now we’re going to build socialism—the Soviet Union existed, it was offering them a certain amount of support and material assistance in doing it. And they didn’t have any other model. And they didn’t right away recognize that the model of the Soviet Union first of all had problems in it anyway, and second of all wasn’t necessarily suited to the concrete conditions of China. So the emphasis the Soviet Union under Stalin put on developing heavy industry, you know, to the disadvantage of agriculture and so on, was an even bigger problem for China than it was in the Soviet Union, although it caused real problems there.3 So at a certain point, Mao once again, as he did in making the revolution in the first place, comes up against the realization, after maybe a decade or so of experience in trying to build socialism in China, that this Soviet model has a lot of problems with it. You know, its over-emphasis on heavy industry. That’s not the way we’re going to actually get the peasantry to be on the socialist road, by sacrificing everything just to one-sidedly develop heavy industry, and so on.

Communal dining room in a people's commune during the Great Leap Forward, 1959. People's communes were a new thing that, under communist leadership, brought together millions of peasants to collectively work the land and transform relations between and among people.

So Mao was trying to break out of this model. And that’s really what the much-maligned Great Leap Forward was about.4 Plus the Soviets, once Mao did try to break out of this model and not be under the wing of the Soviets, turned against him, supported people in the Chinese Party who wanted, if not to overthrow him, then force him to go back under the Soviet model and Soviet domination, in effect, and [the Soviets] pulled out their assistance, their blueprints, their technical aid, and so on, right when the Chinese are trying to make a leap in their economy.

So Mao is trying to forge this road in China for socialism, just as he did before, for the road for actually getting power. Now they have power. He’s trying to forge a different road for socialism. But he’s up against not only the Soviet Union but a significant section of the Chinese Party. On the one hand, a lot of them really didn’t break out of the—as Marx said, they really didn’t get beyond the horizon of bourgeois right. They really were still thinking in terms of just—as Deng Xiaoping openly implemented after he came to power—how do we make China a powerful country, even if it means doing it with capitalism? And they weren’t really thinking about how to get to communism as part of the whole world struggle. So you have that phenomenon. And then you have the phenomenon that a lot of the people, to the degree that they are trying to build socialism, are doing it with the Soviet model, and with the methods the Soviet Union used (which we talked about somewhat) as the way you go about doing this. And Mao is trying to figure out how to break out of this, and how to actually have a socialism that much more brings the masses consciously into the process. Mao criticized Stalin, for example, when, in the early ’60s, he was commenting on some of Stalin’s writings about socialism—he said Stalin talks too much about technique and technical things and not enough about the masses; and he talks too much about the cadre and the administrators, and the technical personnel, and not the masses and not enough about consciousness.

So in those ways, too, he was trying to fight for a different model of socialism that would really bring the masses much more consciously into the process. And then, on top of that, the educational system, the culture—all that superstructure, as we describe it—was really unchanged from the old society. A lot of people, even in the Communist Party, didn’t see the problem with the traditional Chinese culture, even though it had a feudal content to it, to a very significant degree, and even though it sort of uncritically repeated or adopted things that came from these imperialist countries that had dominated China. So Mao was saying: how do we break out of this mold that’s not really going to lead us to where we need to go in terms of building socialism in China?

He’s up against people who are not really that much motivated by transforming the whole society, you know, in terms of getting rid of all the unequal relations and oppressive divisions, but just want to build up a powerful country. He’s up against people who, to the degree they even do think about that, are thinking of it in the terms of what the Soviet Union under Stalin had done (and the Soviet Union under Khrushchev5 was modifying but still carrying forward some aspects of it in terms of this way to build the economy). And he’s up against a whole culture and superstructure that’s still reinforcing the old relations from the past. And he tries various methods.

I’m saying “Mao.” It’s not just him all by himself, but to a significant degree, to be honest, it was him by himself. Because not that many other people in the leadership of the Party even recognized these contradictions and saw that it was going to take them somewhere other than [where] they wanted to go, and ultimately back to a form of capitalism. So to a significant degree, although there were some few others in the leadership, mainly there weren’t. It was mainly Mao who was the one who was saying: We have to break through and do something different here.

And he tried things like initiating socialist education movements, that through the channels of the Party would raise the sights of the Party members and the masses more broadly as to why they needed to build socialism in China, and what that meant, and what that had to do with transforming the economic relations of people in production, and the social relations between men and women and various other important social inequalities that needed to be overcome, and the political structures and the culture. But that only got so far, and really didn’t get to the heart or the root of the problem: that there were all these forces taking China back toward capitalism, even if in a slightly different form, a combination of copying what was done in the imperialist countries, and what had been done in the Soviet Union—which, in the conditions of China, repeating that would have led back to capitalism, as Mao was increasingly recognizing.

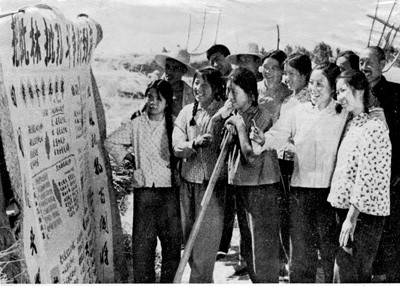

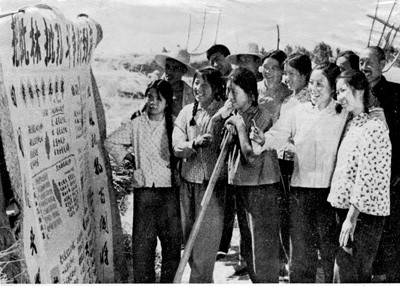

University students in Peking posting big character posters, a form of mass democracy through which the people could express their views on major economic, social, political and cultural issues.

So all this is the backdrop—the reason I’m going into this much detail—this is the backdrop for why the Cultural Revolution was necessary. And Mao said, at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution: we tried various ways to solve this problem, that we were being taken back down the road to capitalism. I mean, the Soviet system—part of Mao’s criticism was it also involved things like one-man management in the factories, instead of really bringing the workers increasingly into administrative and other, similar tasks, and into the development of technology, and the planning of technology, the planning of production. They just basically froze in place the old relations, within the framework of state ownership, and they basically reproduced the same relations in that framework. That was a big problem with the Soviet model of socialism. Mao was increasingly recognizing this. And they [the Soviets] were doing other things that are familiar in capitalist society, like motivating people with piecework and bonuses, rather than trying to motivate them ideologically to want to raise production in order to advance the revolution in China and support the revolution worldwide.

So Mao’s saying: We have to sweep away this stuff, but we’ve tried doing it through the channels of the Party, through things like socialist education movements, and they haven’t really worked, because the way the Party is structured and the way that the leadership of the Party—most of the leadership of the Party conceives of socialism just in a way that’s actually going to lead away from socialism. So if we just do it through the channels of the Party, it’s just going to end up going nowhere, or end up ironically reinforcing what we’ve already got. We need something radically different to rupture out of this—to transform what’s going on in the economy, to transform what’s going on in terms of how the actual decision-making goes on in the society, transform the culture and the thinking of the people. So this is finally—Mao said finally we found the form in the Cultural Revolution, a form through which, as he put it, the masses could expose and criticize our dark aspect, our negative side, in a mass way and from below.

The Cultural Revolution: Its Aims, Its Methods, Its Contradictions

BA continues: And that’s really what they were setting out to do with the Cultural Revolution, which is—the reason I’m going into all of this background is that Mao was trying [to deal with] a really tremendously challenging, difficult thing: to rupture them off one road, really, onto another. Even though the society was still, in an overall sense, socialist, it was very rapidly heading back to capitalism because of all the pulls I’m talking about. And Mao recognized: unless we rupture it somewhere else, the process of attrition, almost, is going to wear us down back to the capitalist road.

So all that is what he was really setting out to do, and he recognized that in doing this, you can’t rely on the same channels of the Party that are sort of sclerotic and frozen in these old ways of seeing what this is all about, with this bourgeois idea of just getting China to be a powerful country playing its own rightful role in the world—and, to the degree that anybody thinks about socialism, it’s the Soviet model, which has a lot of things in it that are actually carryovers from capitalism.

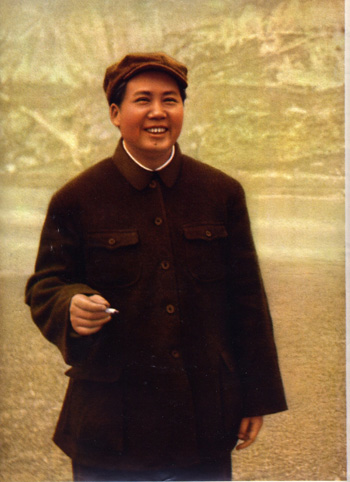

Mao Zedong

So you’re not just going to be able to go through the channels of the Party to solve this problem, Mao recognized. So we have to have some upheaval that comes, as he said, from below, and in a mass way. And that’s where the whole phenomenon of the youth—who are often the force that’s willing to criticize and challenge everything, and is not just stuck in convention. They were unleashed—you know, the Red Guards—to actually challenge this whole direction, including to challenge the Party leaders and Party structures that were the machinery for carrying things in this direction that Mao recognized would go back to capitalism, for all the combination of reasons that I’m discussing. So that’s really what they were trying to accomplish, and they were trying to make changes in the way society was administered, to draw the masses in; changes in how, for example, health care was done so that it wasn’t only for the city and only for the better-off strata, but was spread out to the countryside where the masses had never had health care. All these were issues that were bitterly fought out in the Cultural Revolution.

And the culture began to put the masses of people—but, more importantly, revolutionary content—onto the stage, instead of old feudal themes, and emperors and various upper-class figures like that as the heroes.

Mass Upheavals, Revolutionary Struggles, Excesses, and the Larger View

BA continues: So this was what they set out to do. And I think a lot of these horror stories that we hear about from the Cultural Revolution—I think that there’s some reality to what people describe—there were excesses. But they [these horror stories] also reflect a very myopic view where a small, more privileged section of society raises its concerns and needs above the larger thing that was happening to the masses of people in the society as a whole. I mean, I’ve made this analogy. Some people complain: well, intellectuals were made to go to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution; but nobody ever asked the peasants, who made up 80 or 90 percent of the population, whether they wanted to be in the countryside. It was just assumed they would be there, producing the food and the materials for clothes and so on, while other people were in the cities, having a more privileged existence, especially if they were from these strata other than the proletariat.

So that’s one side of the picture. I think that there were excesses. I mean, Mao commented on a peasant rebellion that he went to investigate in China during the 1920s, at the beginning of the revolutionary process, and he made this statement: the peasants are rising up, challenging all the old authorities and overthrowing them, and some people are saying, oh, it’s terrible, it’s going too far. And he said: look, we basically can either try to get to the head of this and lead it, we can stand to the side and gesticulate at it and criticize it, or we can try to stand in the way and stop it. And he also, along with that, said: if wrongs are going to be righted, there will inevitably be excesses, when the masses rise up to right wrongs, or else the wrongs cannot be righted. If you start pouring cold water and criticizing and trying to tamp things down as soon as there are any excesses, then things never get out of acceptable bounds—and if things don’t get out of acceptable bounds, fundamental changes don’t come about. So the same thing applied in the Cultural Revolution.

There were excesses. Mao said to Edgar Snow, when he was interviewed by him in 1971, that he was very disappointed by some of the excesses that occurred and some of the ways in which people carried out struggle in unprincipled ways. And he was very disappointed that there was factionalism that developed among the Red Guards, instead of uniting people broadly around the broad themes of the Cultural Revolution as I’ve tried to outline them. They got into factional disputes and began to actually war with each other. Sometimes literally with arms over which was the one that was the only revolutionary force and all the others were counter-revolutionary. So you know, while he was disappointed and even expressed his disappointment with some of this, he also recognized that the same principles were at work—that if there weren’t a mass upheaval, you were not going to be able to rupture things off the road they were on, and they would very quickly go back to capitalism, for all the reasons I’ve been trying to point to. But if you did have a mass upsurge, you would have excesses. And then Mao tried to move to correct these excesses.

But it’s not possible—first of all, this isn’t like the caricature they paint, like one person sits here and stage-manages the whole thing and literally presses buttons and controls [everything]. The thing is a mass upsurge. It was a revolutionary struggle. I mean, they did overthrow the established leadership of the city of Shanghai through a million people rising up, and replaced it with a revolutionary headquarters, a revolutionary committee, which brought to the fore and incorporated a lot of the masses who’d risen up in these Red Guard groups, including not just students, but workers in the city, and peasants from the countryside around Shanghai. So it was a real revolution—and real revolutions are not neat and clean.

A women's brigade in a commune pauses to read a big character poster, an announcement in 1969 about the 9th Party Congress, summing up the lessons up to that point of the Cultural Revolution.

They did issue directives that tried to give general guidelines to the struggle—including narrowing the scope of the people that were identified as enemies to a small handful of people in the Party who, as Mao put it, were people in authority taking the capitalist road; that among the intellectuals and in academia, they should draw distinctions between a handful of bourgeois academic tyrants who were trying to lord it over people and impose the old feudal and bourgeois standards, and a larger number of intellectuals who were trained in the old society and had a lot of the outlook from that society, but were people that were friends of the revolution and should be won over, even if there were contradictions there. So Mao put out guidelines to try to deal with his understanding that there would inevitably be excesses.

But it was a massive thing of hundreds of millions of people. And a lot of people jumped into it, and some people deliberately carried it to excess in order to sabotage it. People who were at the top who wanted to deflect the struggle away from themselves and what policies and lines they represented would foment factionalism and would carry things to excess deliberately, in order to discredit it, so that then they could step in and say: see it’s all gotten out of hand, we have to put a stop to it.

So this is all the complexity of that. And I have no doubt that there were people who were wrongly victimized in the Cultural Revolution. It’s almost inevitable in this kind of thing. Which doesn’t mean it’s fine, it’s OK. As I said, Mao was upset about some of these things. But, on another level, if you’re going to have a mass revolution to rupture the society more fully onto the socialist road and prevent capitalism—which is what they did—and even to completely restructure and revolutionize the Party in the course of that—which they also did. They basically suspended the Party and disbanded and then reorganized it on the basis of the masses being involved in criticizing Party members, and even having mass criticism meetings where the Party would be reconstituted, as part of mass meetings where the masses would raise criticisms of the Party and evaluate Party members. This was an unprecedented thing in any society, obviously, but including in socialist society. And a lot of errors were made. So that’s one dimension to it.

The Red Detachment of Women (1964) was one of the most popular model revolutionary operas created during the Cultural Revolution in China. Combining beautiful, stirring music with incredible and innovative ballet—the story takes place in the 1930s during the war of liberation. A young woman slave escapes a brutal landlord and joins a women's detachment of the Red Army. During the Cultural Revolution, the masses of people—but, more importantly, revolutionary content—were projected onto the stage, instead of old feudal themes, and emperors and various upper-class figures like that as the heroes.Works like The Red Detachment of Women were part of developing a new art and culture in socialist society–as part of revolutionizing all of society.

Questions of Art and Culture, Matters of Viewpoint and Method

BA continues: Another dimension is, I do think there were some errors of conception and methodology on the part of the people leading this—maybe Mao to some degree, but especially people like Chiang Ching and others who put a tremendous amount of effort into bringing forward these advanced model revolutionary cultural works, which were really world-class achievements in revolutionary content, but also in artistic quality: the ballets, and the Peking operas and so on. But who also I think, had certain tendencies toward rigidity and dogmatism, and who didn’t understand fully the distinction between what goes into, of necessity, creating model cultural works, and what should be broader artistic expression, which might take a lot of diverse forms, and not only could not be, but should not be supervised in the same way and to the same finely-calibrated degree as was necessary in order to bring forward these completely unprecedented model cultural works.

And there needed to be more of a dialectical understanding, I think—and this is tentative thinking on my part, because I haven’t investigated this fully and a lot more needs to be learned, so I want to emphasize that—but I have a tendency to think that there needed to be a better dialectical understanding of the dialectical relation between some works that were led and directed in a very finely detailed and calibrated way from the highest levels, mobilizing artists in that process, and other things where you gave a lot more expression to a lot more creativity and experimentation, and you let a lot of that go on, and then you sifted through it and saw what was coming forward that was positive, and learning from different attempts in which people were struggling to bring forward something new that would actually have a revolutionary content, or even that wouldn’t but needed to nevertheless be part of the mix so that people could learn from and criticize various things and decide what it was they wanted to uphold and popularize and what they didn’t. So I think there’s more to be learned there.

I also think there was a third dimension to this. There was an element, even in Mao—and I’ve criticized this, you know, it’s controversial, but I’m criticizing something that [has been pointed to] in various things I’ve written or talks I’ve given, in particular one called Conquer the World?6—that there was a tendency, even in Mao, toward a certain amount of nationalism. And I think this carried over into some of the ways in which intellectuals and artists who had been trained in and were influenced by or had an interest in Western culture—there was somewhat of a sectarian attitude toward some of that. You know, Mao had this slogan: we should make the past serve the present and foreign things serve China. Well, in my opinion, that—particularly the second part of that—is not exactly the right way to pose it. It’s not a matter of China and foreign things, it’s a matter of—whether from another country, or from China, or whatever country art comes from—what is its objective content? Is it mainly progressive or is it mainly reactionary? Is it revolutionary or counter-revolutionary? Does it help propel things in the direction of transforming society toward communism or does it help pull things back and pose obstacles to that? And I think that formulation, even the formulation of “foreign things serve China”—while it has something correct about it, in not rejecting everything foreign, let me put it that way—has an aspect of not being quite correct and being influenced by a certain amount of nationalism, rather than a fully internationalist view [with regard to] even the question of culture.

MS: That even led to some of the bizarre thing around jazz, right?

BA: Yeah, jazz and rock ’n’ roll. They didn’t understand the positive aspect of that. Of course, there’s a lot of garbage in rock ’n’ roll in particular. They didn’t really understand what jazz was as a phenomenon in the U.S., and they just—they negated it one-sidedly. And they also one-sidedly negated rock ’n’ roll, which in a lot of ways had a very positive thrust at that time, in the ’60s, the late ’60s in the U.S. It had a lot of rebellious spirit and even some more consciously revolutionary works of art were coming forward, even with their limitations. So I think what was bound up with that was also part of what I think got involved in the way some intellectuals in China, particularly those maybe who had more inclinations toward and interest in Western culture, got turned into enemies or got persecuted in ways they should not have.

Factory revolutionary committee members meet with workers.

But this is tentative thinking on my part. We need to investigate it more fully. What I was trying to do, though, was to give the backdrop for why this Cultural Revolution was necessary in the first place, and what they were trying to accomplish with it, and why that was not only legitimate, but necessary and tremendously important and why and how it brought forward all these new things. It did bring forward new revolutionary culture. It did spread health care to the countryside. It did involve masses of people who’d never been involved in science before, in scientific experimentation and investigation, and even scientific theory together with scientists, and the same kinds of transformations in education, the same kinds of transformations in the workplace, where they broke down one-man management and they actually started having administrators and managers and technicians getting involved part of the time—not on a fully equal basis, but part of the time—in productive labor, and having some of the production workers getting involved in those other spheres and having, instead of one-man management, a revolutionary committee that drew in significant representatives of the workers as well as of management or more full-time management and technical personnel and Party cadre.

So there were tremendous accomplishments, including in the sphere of art, including in the sphere of education, including in the whole intellectual sphere broadly speaking. I mean, I read articles from that time in China about physics, theoretical physics, wrestling with the nature of matter and the whole—how to understand the question of motion of matter in different forms that it could assume, not just in everyday things but on a more theoretical physics construct.

So there were a lot of tremendous things that were brought forward. This was not a time when the lights went out intellectually. However, there were shortcomings, and I do believe there were some people who were wrongly persecuted in the course of this; and that, I think, gets mixed into the equation, too.

Artwork created by peasants during the Cultural Revolution.

The Role of Art, and the Artist, and Their Relation to the State

MS: I want to roll on with this. Before I get into the question of actually pursuing more of this question of intellectual and artistic freedom and dissent as a necessity in the future society, I wanted to get into a couple of things about the role of artists in particular. You know, it’s interesting because, 10 years ago, Haile Gerima—I interviewed Haile Gerima, the filmmaker who made Sankofa, Bush Mama. He’s an Ethiopian filmmaker, but he’s been here a long time. He’s kind of been steeped, he’s very schooled in revolutionary theory around the world. And he was influenced a lot by the Cultural Revolution. And one of the things he had, he advanced this idea that the role of the artist in socialist society is to constantly—I’m trying to remember how he actually put it, but it’s to always be opposing the ruling apparatus. He looked at it: the Cultural Revolution went so far but not far enough because this didn’t actually break out that way—that the artists, they stopped short of that.

And then more recently I had the opportunity to interview and spend some time with Ngugi wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan writer, and he has a couple of things that he advances around the nature of art and the relationship between the artist and the state in any society. And one of the things that he talks about is that there’s a conservative part of the state, in that it’s always trying to save itself and preserve its rule and preserve itself, and then that art actually—he says that art, on the other hand, is something that’s always changing. You know, it’s always that—art differs from that, in that it’s always trying to grasp things in their changingness. It’s based on how things are developing, how things are moving and what’s essential and not always what exactly is. And so he sees these two things as being in contradiction to one another, and he says that the artist actually should always be a constant questioner of the state. The artist has a role—his view of the artist in society is that the artist has the role of asking more questions than they do of providing answers, and that’s something that he feels should be enshrined in any society. And I was wondering how that would fit in with your view of socialism and the role of art and the question of artistic freedom and dissent.

BA: Well, I think from what you’re describing and characterizing, briefly quoting, I think there’s an aspect of truth to that, but it’s one-sided, it’s only one side of the picture. About 15 years ago I gave a talk called “The End of a Stage, the Beginning of a New Stage,7 ” basically summing up, with the restoration of capitalism in China following the same unfortunate outcome as the Soviet Union, that we had come to the end of a certain stage beginning with the Paris Commune, more or less, and ending with the Chinese Revolution being reversed and capitalism being restored there. And now we had to regroup and sum up deeply the lessons, positive and negative, of that and go forward in a new set of circumstances where there were no more socialist countries temporarily. And, at the end of that [talk], one of the things that I tried to set forth was certain principles that I thought should be applied by a Party in leading a socialist society. And one of those was that it should be a Party in power and a vanguard of struggle against those parts of power that are standing in the way of the continuation of the revolution. And I actually think that’s a more correct way, a more correct context, or analogy, for how to evaluate the role of art in particular in a socialist society. In other words, by analogy, I think art should not just criticize that [socialist] state, it should criticize those things in the society—including in the state, including in the Party, including in the leadership—that actually represent what’s old and needs to be moved beyond. Not necessarily what is classically capitalist but what has turned from being an advance into an obstacle—because everything, including socialism, does advance through stages and by digging more deeply into the soil the old is rooted in and uprooting it more fully. So things that were advances at one point can turn into obstacles or even things that would take things back, if persisted in.

COMMUNISM: THE BEGINNING OF A NEW STAGE

A Manifesto from the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA

Available in English, Farsi, German, Portuguese, Spanish and Turkish from RCP Publications, P.O. Box 3486, Merchandise Mart, Chicago, IL 60654

$5 + $1 shipping. A draft translation into Arabic is now available online. See all translations here.

So I think art needs to criticize all those things. But I think it also needs to uphold—and even, yes, to extol and to popularize—those things that do represent the way forward, including those things about the state. The state in socialist society is not the same as the state in capitalist society. It’s the state that, in its main aspects—so long as it’s really a socialist society—represents the interests of the masses of people, makes it possible for them, provides the framework within which, they can continue the revolution and be defended against enemies, both within the country and the imperialists and other forces who would attack and try to drown that new society in blood from the outside. So the state has a different character, and as long as its main aspect is doing those things—is actually representing rule by the proletariat in which the proletariat and broad masses of people are increasingly themselves consciously involved in the decision-making process and in developing policies for continuing the revolution—wherever that remains the main aspect, those things should be supported and even extolled. But even within that, even where that is the case, there will be many ways in which there will be not only mistakes made but things which have come to be obstacles, ways in which in the policies of the government, and the policies of the Party, and the actions of the state, [there are] things that actually go against the interests of the masses of people—not just in a narrow sense, but in the most fundamental sense even, in terms of advancing to communism—and that actually pose obstacles. And those things should be criticized.

And I do think there is a truth to the idea that artists tend to bring forward new things—although that’s not uniformly true. Some artists—the same old thing over and over, you know, very formulaic—and especially those whose content seeks to reinforce or restore the old, it often isn’t that innovative. Sometimes even that is good [artistically]; often it isn’t. But I do think there is some truth that there is a character of a lot of art that it’s very innovative and it tends to shake things up and come at things from new angles and pose problems in a different way or actually bring to light problems that haven’t been recognized in other spheres or by people who are more directly responsible for things, or by people who are more directly involved in the politics of a society. And I think there should be a lot of freedom for the artists to do that. But I also think part of their responsibility, and part of what they should take on, is to look to those things that are—that do embody the interests of people—including the state. And they should popularize and uphold that, because there are going to be plenty of people wanting to drag down and destroy that state. But I think there’s not a clear enough understanding of the fundamental distinction—even with all the contradictions involved that I’ve been trying to speak to—the fundamental distinction between a proletarian state, a state in socialist society, and a bourgeois state which is there for the oppression of the masses and to reinforce the conditions in which they’re exploited, as the whole foundation of this society, and [which] viciously attacks any attempt to rebel against, let alone to overthrow, that whole system.

So I think there is importance to drawing a distinction—and then, once you recognize that fundamental distinction, then once again, as we say, divide the socialist state into two. What parts of it are power that embodies and represents the interests of the masses in making revolution and continuing toward communism, and what parts have grown old or stand in the way of that continuation? Extol the one, popularize the one; and criticize and mobilize people, encourage people to struggle against the other.

The Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America (Draft Proposal) from the RCP is written with the future in mind. It is intended to set forth a basic model, and fundamental principles and guidelines, for the nature and functioning of a vastly different society and government than now exists: the New Socialist Republic in North America, a socialist state which would embody, institutionalize and promote radically different relations and values among people; a socialist state whose final and fundamental aim would be to achieve, together with the revolutionary struggle throughout the world, the emancipation of humanity as a whole and the opening of a whole new epoch in human history–communism–with the final abolition of all exploitative and oppressive relations among human beings and the destructive antagonistic conflicts to which these relations give rise.

The Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America (Draft Proposal) from the RCP is written with the future in mind. It is intended to set forth a basic model, and fundamental principles and guidelines, for the nature and functioning of a vastly different society and government than now exists: the New Socialist Republic in North America, a socialist state which would embody, institutionalize and promote radically different relations and values among people; a socialist state whose final and fundamental aim would be to achieve, together with the revolutionary struggle throughout the world, the emancipation of humanity as a whole and the opening of a whole new epoch in human history–communism–with the final abolition of all exploitative and oppressive relations among human beings and the destructive antagonistic conflicts to which these relations give rise.

Read the entire Constitution for the New Socialist Republic in North America (Draft Proposal), authored by Bob Avakian and adopted by the Central Committee of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA, at revcom.us/rcp.

Revolution, Leadership, State Power, the Goal of Communism, and the Importance of Dissent and Ferment—Solid Core and Elasticity

MS: One of the things that sets you against a lot of the past experience of socialist societies, of Marxist thinkers and whatnot, is the point about not just allowing dissent, not just allowing this kind of breadth of exploration among people who work with ideas and among artists and whatnot, but actually talking about the necessity of that to exist. Why do you think that that’s necessary and not just something to be tolerated?

BA: Well, I’m currently wrestling with the question of how you can have that within the Party, and the relation between having that inside the Party and in the society at large, and how you do that without losing the essential core of what you need to hold onto in order to actually have state power when you get it, and in order to actually go on toward communism, rather than getting dragged back into capitalism. So that, to me—that’s something I’m grappling with a lot. It’s a very difficult contradiction.

But to go directly to your question: I think the reason you need it is because if people are going to be fully emancipated—you know, Marx said that the communist revolution involves a transition to what we Maoists have come to call, by shorthand, the “4 Alls.” He said: it’s the transition to the abolition of all class distinctions (or I think literally he said, “class distinctions generally,” but it’s the same thing) and to the abolition of all the relations of production, all the economic relations on which those class distinctions rest; the transformation or abolition of all the old social relations that correspond to those production relations—like oppressive relations between men and women, for example—and the revolutionizing of all the ideas that correspond to those social relations. So if you look at those “4 Alls,” as we call them, and the objective is to get to those “4 Alls,” then that can only be done by masses of people in growing numbers consciously undertaking the task of knowing and changing the world as it actually is, as it’s actually moving and developing and as it actually can be transformed in their interests. So if that’s the way you understand what you’re after and how fundamentally that’s going to be brought about—and not by a few people gathering everybody in formation and marching them in a straight road forward in very tight ranks—then you understand that a lot is going to go into that process. The socialism that I envision, and even in a certain way the Party that I envision, is one that’s full of a lot of turmoil, one that would give the leaders of it a tremendous headache, because you would have all kinds of stuff flying in all kinds of directions while you’re trying to hold the core of all that together and not give up everything.

I had a discussion with a spoken-word artist and poet, and I was trying to describe these things I’m characterizing here—what I’m grappling with as it applies to the arts and lots of other things—and he finally said to me, and I thought it was a very good insight: he said, it sounds to me like what you’re talking about is a solid core with a lot of elasticity. I said yeah, well, that’s very good—because he put together in one formulation a lot of what I was wrestling with.

But it is—how do you keep that solid core so you don’t lose the revolution? Let me be blunt. You need a vanguard, you need a Party to lead a revolution and to be at the core of a new society. When we get there, we’re not going to hand power back and we’re not going to put power up for grabs or even up for election. We’re not going to have elections to decide whether we should go back to the old society. In my view that should be institutionalized in a constitution. In other words, the constitution will establish: this is a socialist society going toward communism. Will establish what the role of the Party is in relation to that, and will establish what the rights of the masses of people [are] and what the role of the masses of people is in fundamentally carrying that out—including, as I see it, having some elections on local levels and some aspects of elections from local levels to a national level, which are contested elections within that framework of going forward through socialism to communism and having spelled out, in some fundamental terms (not in every detail), what that basically means and doesn’t mean, in a constitution, in laws, that the masses of people increasingly themselves are formulating and deciding on.8

But we’re not going to just say: “OK, we’ll have socialism and then we’ll give it back to them [the capitalists] and see if the people want it [socialism] again. If you do that, you might as well not bother to make a revolution. Because think about everything we were talking about earlier, and everything you have to go up against—if you’re going to have an attitude like that, you don’t have any business putting yourself forward to lead anything, because you’re not serious. To make a revolution is a wrenching process, and to continue on the road forward toward communism and to support the world revolution in the face of everything that will get thrown at you is going to be an extremely arduous and wrenching process, and you have to have a core of people who understands that, even as that core is constantly being expanded. I’ve set forth—when I say “set forth,” I don’t mean to make it sound like a proclamation, this is what I’m thinking about, this is what I’m wrestling with—that there’s four things that this core has to accomplish, four objectives. You have to maintain power, at the same time as you make that worth maintaining. And the four objectives I’m talking about are:

One, that core has to hang on to power and lead the masses of people to not be dragged back to the old society—not hang on all by itself, but it has to be determined to hang on to power and mobilize the forces in society that could be won at any given time to seeing that you have to hang on to power and hang on to the revolutionary direction forward.

Two, it has to be constantly expanding the ranks of that core, so you’re not just talking about the same relative few—even if you’re talking about hundreds of thousands or millions, the same relatively small section of the population relative to say a country like this. But is it constantly expanding, constantly in waves drawing in broader ranks to be part of that core of this process?

Three, that it is guided constantly by the objective of eventually moving to where you don’t need that core anymore, because the distinctions that make it necessary have been overcome.

And four, that at every point along the way there’s the maximum elasticity that you can have without destroying that core.

So this is what I am wrestling with in terms of this process. And to me this is the furthest thing from everybody marching forward in tight formation, although there are times when you have to do that—when you’re directly under military attack, you have to tighten your ranks up. But, in general, I see it as a very wild and woolly process, if you will, where people are going in different directions and the responsibility of the leadership, of this leading core, is to try, as I put it before, to get your arms around all that—in the sense of an embrace, not in the sense of squeezing it and suffocating it—keeping it going toward where it needs to go and drawing more and more people into the process of doing that.

So seen in that way, this is a very tumultuous thing. And I think there’s even a way in which the Party has to be like that. That this principle of “solid core with a lot of elasticity” has to apply even within the Party, because I’ve been wrestling with the question: can you really have ferment, intellectual ferment, artistic creativity and ferment and experimentation in a society, in a socialist society at large, if you don’t have it within the Party that’s at the core of it? I don’t think you can. If the Party doesn’t have that, then it’s gonna suffocate it in the society. It’s going to be too much uniformity coming from the Party, which has a lot of influence, and so it’s going to tend to stifle and suppress that [creativity and ferment]. So how do you have a solid core and elasticity even within the Party in general, over policy but also as applied to the arts and to the intellectual sphere in the broadest sense, and so on? And, to draw an analogy from physics here, even a solid core—you know, everything is contradiction and whatever level you go to it’s contradiction—so a solid core is solid in one sense, but within it, it also has elasticity. Because if everything is packed together too tightly in your core, so to speak—to continue to torture this metaphor—but if it’s all packed together too tightly in the core, then you don’t have any life in there, so you can’t have the elasticity.

So I see this as a very moving, tumultuous thing. On the one hand, we’re not giving power back and we’re not putting that up even for a vote—and, on the other hand, we’re also not all marching everybody straight down the road, but we’re having all kinds of tumultuous struggle, including within that people who want to go back to capitalism throwing their ideas into the ring. While we supervise the overthrown exploiters and curtail their political activity, and while people who have been demonstrated—through legal processes shown—to be active counter-revolutionaries, in the sense of their actually taking up concrete acts of sabotage, or what we would now call “terrorism,” against the new society (blowing up things, assassinating people, or actively, not in some vague sense, but actively plotting to do that), that’s one thing. I think you need a constitution, laws and procedures to deal with those people. But beyond that, in the realm of ideas, even people who argue that capitalism is better than socialism—those ideas need to be in circulation, and people who want to defend those ideas have to be able to do so, so that the masses of people can sort this out.

And we have to defeat them in the realm of ideas as well as in practice. Right now, we do that all the time. Our attitude now is somebody wants to defend capitalism—bring on all comers, let’s have a debate. We can’t get these [bleep] to debate us! That’s what’s frustrating to us. So my attitude is: yes, things are changed [once you get to socialist society]; there is a new set of circumstances; we are going to be at the core of leading the masses of people. That’s our responsibility. But we shouldn’t be any less anxious to have those debates and to thrash those things out, and to get many more people in them. Why should we fear that then in a way that we don’t now? We welcome it now, so why shouldn’t we welcome it [then]?

I will tell you that, as I envision this, it gives me a headache because I can see how hard it would be to keep all this going in the forward direction it needs to go. But if you aren’t willing to risk that, then I don’t think we can get where we need to go.

FOOTNOTES

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/260/study_guide_from_a_reader-en.html

Revolution #260 February 19, 2012

Letter from a Reader

On studying Bob Avakian on the Cultural Revolution and the role of the artist in socialist society

February 12, 2012

To the editors:

I was very glad to hear that Revolution is publishing Michael Slate's interview with Bob Avakian on the Cultural Revolution in China, and the role of the artist in socialist society. I've recently used this interview in two different study sessions with people who from various viewpoints are getting into the RCP's Manifesto and BA's new synthesis of communism, and I want to share that experience and make a recommendation.

First off, I used the audio of the interview itself, which is available online. I didn't make a presentation with my own interpretation of what was said, and I didn't just ask people what they thought of the content; I played it. I would suggest doing the same. Even if people have read it, this interview is deep and layered, and stands repeated listening. In addition, for this generation the content of what's being discussed is very unfamiliar. So hearing it again will refresh people as to its content. (If you are leading discussion of this in prison or otherwise are unable to play an audio, perhaps someone could read the content out loud, and then stop at various points.)

When I led the classes, I began with an orientation that laid out the importance of BA and the work that he has done, including very importantly on the experience of the first stage of the communist revolution; that this first stage—the great achievements, as well as the setbacks—is critical for us to understand if we are going to truly initiate a new stage of this revolution; and that our approach has to be scientific and not religious—we are trying to deeply understand reality, not reassure ourselves as to the "tenets of the faith" or tell ourselves tales of a "golden age" to buck up our spirits or spend an evening discussing something interesting for the sake of discussion (though it is interesting!). This is about learning how to do better the next time. Of course, a program in a bookstore should draw a very broad audience, including people who are checking this out for the first time, and we should take care to be inclusive (to have "big arms," to put it that way); but this orientation should be the leading edge.

This orientation was relatively brief. Then the session proceeded like this: I would play a section of audio, and then stop and ask a few questions on the content. This wasn't random—to do this well, you have to listen to the audio a few times and figure out where the important points are to stop. For example, at one point BA discusses the "birthmarks" of capitalism in the new society—in one group we stopped there and discussed for a while what that actually refers to. In the course of this, people raised many questions and there was quite a bit of discussion and debate. In the other session, in discussing the part of the interview where BA compares Mao's approach to Stalin's, someone raised, "yeah, well you can say all that, but let's face it—Stalin had no choice." This too led to some really engaged discussion and debate. The point is this: by playing the audio and stopping it occasionally, the discussion stayed focused on the content of the material as the solid core—and the elasticity of the discussion (ranging over different concepts discussed by BA and experiences of the first stage of communist revolution) revolved around that. I won't and can't go into all of what we discussed, but we did dig deeply—and one of these discussions, which took place in the afternoon, went well over 4 hours before we finally had to leave to make way for another program. A few major themes: the need to be scientific (and we reviewed what that is), to learn from the content but also the approach of BA, and to do all this coming from understanding that the world really needs a new stage of communist revolution—and the responsibility to bring forward those initiators and be those initiators is before us.

Another way to go at this would be to play the whole interview all the way through, and then focus on key points for discussion. Leaders of the classes should decide which way will work best in their situation.

Second, these discussions actually did NOT go into the second part of the interview—they did not get to the criticisms of Mao and the role of the artist in socialist society. We will do this, but we just weren't able to in one session and I don't think we could have and really have done justice to the first part of the interview. So I would strongly recommend that if discussions of this are being planned—and I strongly feel that they should be—that these be conceived of as two sequential discussions.

Through the course of these discussions, you should be directing people to the RCP's Manifesto, Communism: The Beginning of a New Stage. This document captures the sweep of history and the juncture we're at now—it's really the essential grounding for anyone who wants to understand the historical context of this interview. I would also strongly recommend that people leading these discussions review and, frankly, steep themselves in other works by BA going into this, as well as the polemic against Alain Badiou, the Manifesto, and the appendix in the Party Constitution on the science of communism; there is a hunger among some people right now to learn more and go deeper—to take one example, someone at one point asked "Could you please explain what happened in the GPCR?" This led to interesting discussion where different people put forward their understanding of that, and it was very important to be able to draw on the polemic with Badiou, for instance, in sorting this out.

But again, above all, stay with the interview itself. It's packed! There's nothing more important than bringing forward initiators of a new stage, and this is a very valuable tool in doing that.

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/260/260BA-everywhere-en.html

Revolution #260 February 19, 2012

BA Everywhere—

Imagine the Difference It Could Make

BA Everywhere is a campaign aimed at raising big money to project Bob Avakian's voice and works throughout society—to make BA a household word. The campaign is reaching out to those who are deeply discontented with what is going on in the world, and stirring up discussion and debate about the problem and solution. It is challenging the conventional wisdom that this capitalist system is the best humanity can do—and bringing to life the reality that with the new synthesis of communism brought forward by BA, there is a viable vision and strategy for a radically new, and much better, society and world, and there is the leadership that is needed for the struggle toward that goal.

Success in this campaign can bring about a radical and fundamental change in the social and political atmosphere by bringing the whole BA vision and framework into all corners of society where it does not yet exist, or is still too little known, and getting all sorts of people to engage and wrestle with it.

BA Everywhere is a multi-faceted campaign, involving different key initiatives and punctuation points, at the same time sinking roots among all sections of the people and reaching out broadly in myriad creative ways. Revolution newspaper is where everyone can find out what's going on with all this: reports on what people are doing, upcoming plans, important editorials, etc. We call on readers to send us timely correspondence on what you are doing to raise money for BA Everywhere, why people are contributing, and what they are saying.

This week in Revolution, we have a report from the BAsics Bus Tour, which hit the road last week, and a letter from a prisoner, "Every Page Packed With Liberating Knowledge".

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/260/260BA-bus-tour-lets-go-en.html

Revolution #260 February 19, 2012

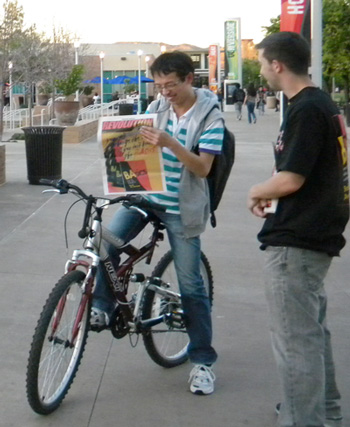

“Let’s Go!”—Report from the BAsics Bus Tour

“Let’s Go” was the spirit of the first hours of the BAsics Bus Tour two-week pilot project. The atmosphere changed as the 30-foot RV rolled out, covered from top to bottom with huge front and back covers of the book BAsics, from the talks and writings of Bob Avakian—in Spanish and English—you can’t change the world if you don’t know the BAsics—with the Revolution talk, the online speech by Bob Avakian, on the top of the cab for all oncoming traffic to see... pumping music from a special on-the-road mix CD and “All Played Out” and other audio pieces by BA... and most important, inside were people of all ages, with the ability to reach out in Spanish and English, filled with the desire to change the world and seeing that getting this book into the hands of many, many people and BA known by thousands more being key to that... and, yes, filled with boxes of the book BAsics and the ability to set up on-the-spot showings of the film Revolution: Why It’s Necessary, Why It’s Possible, What It’s All About.

The bus’s first destination was the area of Pico Union in Los Angeles, the most densely populated neighborhood of immigrants in the city and the scene last year of days of mass resistance in response to the murder of Manuel Jaminez by the LAPD. As we traveled through the neighborhood, heads turned and people took copies of the special BAsics issue (Revolution #244, August 28, 2011) and BAsics was sold. On the ground a lot was learned and the whole pilot project nature of this tour—the learning and transforming hourly and daily—took off as people got ready for the next neighborhood, around Revolution Books, which led up to the launch celebration.

|

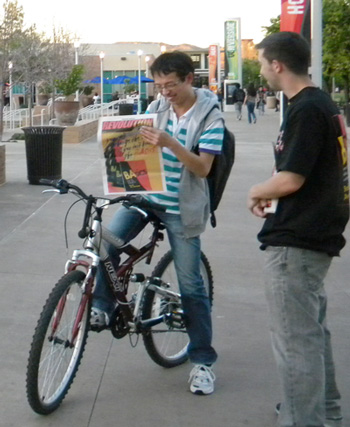

| At UC Riverside |

At noon, people gathered to launch the tour at Revolution Books. Displays with quotes from BAsics—in Spanish and English—lined the sidewalk and music filled the air. Michael Slate, correspondent for Revolution newspaper and host of the Michael Slate Show on KPFK radio, mc’d a program that featured statements by supporters and people who had decided to ride the bus. People heard a description of the many important destinations along the route: rural areas of the state where there is literal starvation and extreme poverty in the midst of the richest farmlands in the country, in the Central Valley of California; college campuses in outlying areas—UC Davis and UC Riverside where the student movement and Occupy were met with extreme brutality by the state, with Riverside being the “diversity” campus for a rapidly disappearing minority student body in the UC system, a campus situated in one of the most economically devastated counties in California; and Orange County, that quintessential symbol of “suburbia” in this country, where a homeless man was brutally beaten to death last July by the police and where the community responded with daily demonstrations.

Statements of support (posted at revcom.us) were read. And there were statements made by three people who will be on the bus. A young woman talked about the BAsics quote that inspired her... where BA talks about his friend who dedicated his life to finding a cure for cancer... and in that quote he talks about joys in taking on the responsibility of changing the world (6:18). A skit was performed, based on BA’s spoken-word piece “All Played Out.” And the program ended with comments by Clyde Young of the Revolutionary Communist Party, who talked about the difference it would make for BA to be known everywhere, for BA to become a household word and a point of reference for people looking to how to change the world. Achieving this goal means raising money to project BA’s vision and works into all corners of society.

The program ended with the words “Let’s Go”... Spirits and resolve were high as the bus hit the road... Next stop: Watts... then out of the city...

The BAsics Bus Tour has now spent a week in Southern California. The bus has been to UC Riverside and to Cal State Fullerton in Orange County. Bus riders did a bookstore reading of Lo BAsico in Santa Ana (the county seat of Orange Country). A dinner for the bus was hosted by Unitarians in Anaheim. Revolutionaries have mixed it up with high school youth in Watts. They performed the skit based on “All Played Out.” This pilot bus—and its riders— are on a mission to lay the ground for a national bus tour—to get BAsics everywhere. And through it all, the tour has met many people and introduced them to BAsics and, in a beginning way, to Bob Avakian.

When the bus rolls down the street, heads turn. One woman said, it “stopped me in my tracks!” People bought BAsics and Lo BAsico, got into the book, and some are now looking forward to getting together to discuss it collectively.

A student at UC Riverside, after learning about Avakian, went on the Internet to do his own research. He came back the next day saying he had learned that BA had worked with the Black Panther Party and was impressed by that. Then he asked are you promoting him or his ideas? We answered: both—that people need to know his work, and BA as a person, and people must defend and protect this leader.

Some people the bus tour has met already have some knowledge of Avakian, but many more people have never heard of BA, his vision and his work. They have not heard of the movement for revolution that we are building. The BAsics Bus Tour is joining with others who are on a mission to change this!

|

| In Watts |

When the bus arrived in Watts, at first the street was quiet, with an occasional passerby. But as a nearby high school let out, the scene changed as Black and brown youth began to pass the bus and its displays.

A loud commotion came toward us from down the street and one student looked over and remarked to her friends, “Here come the wild kids!” Soon there were many youths stopping by the bus, reading the displays of the quotes from BAsics. One youth was holding BAsics in his hands and some others taunted him. The youth told them fiercely to back off, and revolutionaries joined the fray challenging the other youth to engage with BA. It became quite lively as curiosity turned into more serious and sharp discussion and debate on the crowded sidewalk.

The BAsics Bus Tour is part of a campaign to raise big money to project Bob Avakian’s vision and works throughout society, to make BA a household word, to project the whole BA vision and framework into all corners of society where it doesn’t yet exist or is still too little known. And through it all, getting all sorts of people to engage and wrestle with it.

In its pilot project, the bus will roll through Northern and then Central California. Everyone reading this article has an important role to play. There are many ways everyone can be a part of the campaign to raise big money to spread the BA Everywhere campaign. Revolution newspaper urges everyone to donate to and raise money for this tour to go nationwide. Funds are urgently needed so that this tour can head out to communities all over the country.

The BAsics Bus Tour urges Revolution readers to follow the tour on revcom.us, basicsbustour.tumblr.com, and on Facebook (friend BAsics Bus Tour.) Get your audio downloads, video and blog entries at basicsbustour.tumblr.com.

And call to find out the many, many ways you can contribute and join the tour at 323-463-3500.

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/260/letter-from-prisoner-en.html

Revolution #260 February 19, 2012

“Every Page Packed With Liberating Knowledge”

The following letter from a prisoner was sent to the Prisoners Revolutionary Literature Fund:

29 January 2012

Dear PRLF

Revolutionary Greetings! I hope all is well and all your staff finds itself in high spirits.

I’m writing to thank you for a book I received a couple of weeks ago (Marxism and the Call of the Future). The envelope it came in was postmarked Dec. 8, 2011. If I don’t write to thank you soon after you’ve sent me something to read, it will most likely be because prison staff has delayed delivery. I’m done with Marxism and the Call of the Future. I learned a lot and gained a lot from it as I always do from the things you send. I’m studying Communism and Jeffersonian Democracy right now. I’m only a couple of pages into it, but I could already tell that every page is packed with liberating knowledge that must be spread throughout society, including the prison system. I am very grateful for the literature you’ve sent so far and look forward to the day that I could show my appreciation.