Revolution #64, October 8, 2006

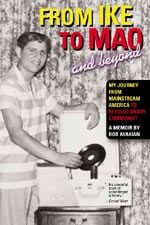

From Ike to Mao and Beyond

My Journey from Mainstream America to Revolutionary Communist

A Memoir by Bob Avakian

From Chapter Four

|

High School

Street Corner Symphonies

I had this friend Sam. Actually I knew him before high school, because I went to a church in Berkeley where his father worked as the custodian and he would come around and help his father sometimes. Then, when I went to high school, he was a little bit ahead of me but we became friends and then we became part of a singing group.

Sam had this one characteristic: when he was eating, he didn’t want anybody to say anything to him. It was just leave him alone and let him eat. I don’t care who it was or what the circumstances were. That was just Sam, you just knew you should stay away from him then, because he didn’t want to talk, he wanted to eat. So one day, I had forgotten to bring my lunch money, and I was really hungry by lunch. I couldn’t pay for anything in the cafeteria or the snack shack, or anything. I was walking all around looking for some friend to loan me some money. So first I went over to Sam and I knew that I was violating his big rule, but I couldn’t help it. I went over and I said, “Sam.” “Leave me alone, man, leave me alone.” I said “Sam, I’m really hungry.” “Leave me alone, I’m eating lunch.” So I just finally gave up there, but I started walking all around looking for someone to loan me some money or give me something to eat or something.

Finally, I saw this guy who had a plateful of food. What particularly stuck out to me was that he had two pieces of cornbread on his tray. And that just seemed so unfair, because I was so hungry and he had not one, but two pieces of cornbread! I just sat down at the table, across from him, and stared for a long time at his plate. He kept looking at me, like “what’s this motherfucker staring at me for?” I just kept staring at his tray. And finally I said, “Hey man, can I have one of your pieces of cornbread?” “No, man, get the fuck out of here.” I said, “Please man, I’m really hungry, I forgot my lunch money. Can I please have a piece of cornbread?” “No man, get the fuck out of here.” I don’t know what came over me—maybe it was just the hunger—but without thinking, I reached over and grabbed one of the pieces of cornbread. He kicked his chair back, jumped up and got ready to fight. So I didn’t have any choice, I jumped up too. He stared at me for a long time—a long time. And then he finally said, “Aw man, go ahead.” So I took the piece of cornbread. Then after that, Sam, who had looked up from his eating long enough to see all this, came over to me—again it was one of these things—and he said, “Man, that was Leo Wofford, you don’t know what you just got away with.” But I was just so hungry, and I guess Leo figured, “oh this crazy white boy, he must really be hungry,” so he just let it go.

Sam lived in East Oakland, but he went to school in Berkeley. A few times I went out to his house—he lived right where East Oakland abutted against San Leandro, and it was like in the south. There was this creek and a fence right outside of 98th Avenue in East Oakland, and if you were Black you did not go on the other side of the fence into San Leandro or these racist mobs would come after you. Sam lived right at the border there.

A few times Sam took me to places and events out in East Oakland. One time we went to this housing project which was kind of laid out in concentric circles, with a row of apartments, arranged in a circle, and then another circle inside that, and then another one. And at the very center was the playground, where there was a basketball court. When we got there, there were some guys getting ready to play ball—I recognized a couple of them who ran track for Castlemont High—so I went over and got in the game. Well, at a certain point, one of these track guys and I got into a face-off—we had been guarding each other, and sometimes bumping and pushing each other, and then it just about got to the point of a fight. Everybody else stood back and gave us room, but after we stared at each other for a while, it didn’t go any further, and we just got back to the game. But, as this was happening, I noticed that Sam, who had been watching at the edge of the court, was turning and walking away.

Another time, Sam and I went to a basketball game between Castlemont and Berkeley High. The game was at Castlemont, but I didn’t have any sense, so I kept yelling shit at the Castlemont players. Their star player was a guy named Fred “Sweetie” Davis, and at one point he got knocked to the floor by a guy on our team. So, I stood up and yelled, “How does it feel to be the one on the floor, Sweetie?” Sam had been trying to get me to stop acting the fool and shut up, and when this happened, he just got up and walked away, like “I don’t know this crazy white boy.” So, sometimes, without meaning to, I put Sam in some very difficult situations.

Sam was a really good singer. So one day I went to him and I asked: “Hey, Sam, you want to start a group?” He thought about it for a while, and then he got back to me and said, “Yeah, let’s do it.” Sam had a cousin named George who played piano, and George could also sing. So Sam said, “Let’s get George in the group.” And there was this other guy, Felton, who was one of the few Black kids who had gone to junior high school where I did. So I went and asked him if he wanted to be part of it, and Felton said “Yeah.” And then I asked Randy, this white kid who’d been part of this impromptu singing group with John and me in our last year in junior high school.

So the five of us—three Black, two white—formed a group. We figured out pretty quickly that Sam should sing lead, at least on most of the songs, and then the others of us took our parts. You have to have a bass, and that was Felton. We had to have a baritone, and that was Randy. Then you had to have a second tenor, which was the lower-range tenor, and that was George. And the first tenor was me. We had this whole thing worked out. Sometimes we practiced at George’s house, because he had a piano in his house, and sometimes we’d go to my house, because we also had a piano. We’d spend three or four hours a lot of days just practicing, working on our music. And we’d sing anywhere we could get together to sing—this was part of a whole thing where people would get together, sometimes in formal groups and sometimes just with whoever was around at the time, and sing everywhere: in the locker rooms before and after gym class, in the hallways and stairways at school, and out on the street corners.

Eventually, Randy left the group and then Odell—Odell who claimed I’d “stepped on his dogs” way back on our first day of school—replaced him. When Odell replaced Randy I reminded him of that run-in we had, and he didn’t even remember it. But he did get a big laugh out of my telling the story. Odell used to write songs—I’d see him out in the hallway: “Hey, Odell, what are you doing, how come you’re not in class?” “I’m writing some songs, man.” We’d practice and we’d try to get gigs, wanting to get paid and get known a little bit.

We had to come up with a name for the group. There was already the Cadillacs, and the Impalas, so we became the Continentals. Now we’d also been rehearsing at the rec center at Live Oak, because they had a piano in there. The director of the rec center heard us and said, “Hey, I like your sound, would you guys be willing to play for this dance we’re having?” We answered, “Yeah, are you gonna pay us?” And he said, “Well, we have a tight budget, but I could pay you something.” So then we all got together and said, “How about a hundred bucks?” He came back with, “How about 25?” We looked at each other and said, “Okay.” ‘Cause any money was good then.

We rehearsed a lot for this, and we came there that night ready to do this Heartbeats’ song, “You’re a Thousand Miles Away,” and some other tunes. As we were about to go in the rec center, this friend of Sam’s who had been playing basketball was coming over to get a drink of water. And he said, “Sam, what are you doing here?” Sam said, “We’re gonna sing for this dance.” “You can’t sing, Sam.” “Yeah I can, man.” So before we could go in to perform for the dance, we had to have a sing-off between Sam and his friend—they both did a Spaniels song, and after a couple of verses the other guy threw in the towel, because Sam could really sing.

Another time my younger sister got us a gig performing at their ninth-grade dance. The other guys in the group said, “Okay man, this is your sister’s thing,” so they let me sing lead on one song—I think it was called “Oh Happy Day.” And that was a lot of fun.

Some of the white parents just couldn’t relate to this music at all. And with some there was a whole racist element in it, because it was the influence of Black culture working its way “into the mainstream.” But a lot of the white youth were taking it up and were really into it, as exemplified by my older sister’s junior high school class voting “WPLJ”* as their favorite song. I think Richard Pryor made this point in one of his routines—when it’s just Black people doing something, then maybe they can contain it, but when it starts spilling over among the white youth, then “Oh dear, everything’s getting out of control.” So there was that sort of shit, and there was a general thing among the racist and backward white kids, where listening to this music and getting into this culture was part of a whole package of “things you didn’t do.” They would give you shit for that, but it was just part of a whole package of everything they were down on, and all the things they’d give you shit for.

Besides singing doo-wop, I was in the glee club in school. When I was a senior, the glee club teacher talked me and three other guys—two of us Black, two of us white—into doing a barbershop quartet song for the talent show. And we did it—with our own little touch to it. Another time, when I was sixteen or seventeen, I went to a Giants baseball game. Right before the game starts they always have the national anthem, and I was still somewhat patriotic—I wasn’t super-patriotic, but I still thought this was a good country overall, even though I was very angry about discrimination and segregation and racism and all that. So we all stood up for the anthem and, for whatever reason, I started singing along. The song finished and this woman in front of me turned around and said, “You know, you have a beautiful voice.” I’ve often thought back on the irony of that.

But it wasn’t very long before I quit singing that. Later, when I would go to ball games and they would play the national anthem, I would stand up and sing, as loudly as I could, a version that someone I knew had made up: “Oh, oh Un-cle Sam, get out of Vietnam. Get out, get out, get out of Vietnam…”

* Editors' note: WPLJ stands for "White Port and Lemon Juice." [back to text]

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.