Appreciating Ornette Coleman:

Jazz Visionary, Cultural Rebel

June 22, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

From a reader:

Ornette Coleman, 2007. (Photo: AP)

The world has lost a towering artistic innovator of the 20th century. Ornette Coleman, the alto saxophonist and composer, was 85 when he died of a heart attack on June 11 in New York City.

Ornette Coleman will be remembered as one of the Great Jazz Masters. But he was much more than this. He rewrote the language of jazz. He changed how people think about, compose, and play music; how people listen to and experience music. He was a great and pathbreaking innovator who had a profound effect not only in the world of jazz, but more broadly in art and culture.

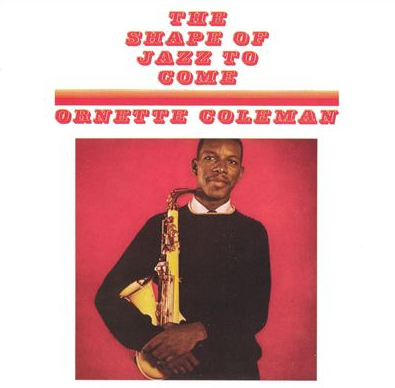

Ornette Coleman was an artist of the times who was also ahead of the times. And he was a catalyst for radical experimentation in the arts. Coming onto the scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s, his music was, as an old Chinese saying puts it, a “wind in the tower that heralds an approaching storm.” His music was at one and the same time denounced and embraced. It was controversial and polarizing. It was a cultural manifesto, reflecting the unraveling of 1950s conformism and the rising struggle of Black people against oppression. And it connected with and inspired different strands of unorthodoxy, upheaval, and rebellion in society. Ornette declared the import and place in history of his music and a new defiant attitude in the titles of his early albums: The Shape of Jazz to Come, Change of the Century, and This Is Our Music.

The Shock of the New

Ornette Coleman was born in Fort Worth, Texas, and took up the saxophone when he was 14 years old. He played in local groups and traveling bands in the South, mainly swing, blues, and some bebop. Then in the early 1950s, he moved to Los Angeles and eventually brought together a group of great musicians who helped him define his music—trumpeters Don Cherry and Bobby Bradford, drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins, and bassist Charlie Haden.

Ornette Coleman Quartet 1960 - Don Cherry (cornet), Ornette Coleman (alto sax), Charlie Haden (bass), Billy Higgins (drums) playing “Ramblin’”

In 1959, things really took off when the Ornette Coleman Quartet (Cherry, Haden, Higgins, Coleman) went to New York City for what became a two-and-a-half-month-gig at the Five Spot Café. The quartet’s stint at the Five Spot was a turning point in the history of jazz—considered by many to be the beginning of what came to be known as Free Jazz.

This was a jazz liberated from traditional structures and conventions—being created at a time when the call and struggle for freedom was taking hold in U.S. society.

The music was immediately controversial. Some in the audience were captivated, others repelled. One New York Times critic wrote that he found Coleman’s playing “shrill, meandering, and pointlessly repetitious.” Some got up, leaving unfinished drinks behind, while others were mesmerized. It became hip not only for other musicians but also many journalists and artists to come hear the group play.

One man came every night, getting up near the stage, leaning in close to the musicians. At one point, Charlie Haden, the band’s bass player, looked over at Ornette and said, “Who is this motherfucker? What is he doing? Tell him to back off.” And Coleman said, “Man, don’t you know who that is? That’s Leonard Bernstein!” (the famous classical conductor and composer). Indeed this music demanded the attention of anyone who considered themselves on the cutting edge of art—and night after night musicians, writers, artists, and others packed the club to hear, like it or not, music no one had ever heard before.

At this time other jazz musicians like John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk were also breaking new ground in jazz, and Ornette brought into this mix shocking sounds and musical concepts that challenged conventional swing and bebop jazz of previous decades. His music became a flashpoint for intense arguments about the very validity of avant-garde jazz. Well-known jazz musicians attacked Ornette’s music, saying it wasn’t even jazz. But others were provoked and inspired, and Ornette’s music had a profound impact on other musicians. In 1961 John Coltrane said that the 12 minutes he had spent on stage with Coleman amounted to “the most intense moment of my life.” (New York Times, obituary, June 12, 2015)

Ornette Coleman’s music was the product of all kinds of musical and cultural influences. But his ground zero was blues and jazz, which has been indelibly stamped with the oppression of Black people in this country. And Ornette’s journey as a maverick artist and as a Black man in racist AmericaKKKa was also part of what shaped his music. He told stories of being beaten up—sometimes he didn’t know if it was because he was a Black man or the way he played, or both. There is the time early on, when a white man came up to him after a performance in Texas and said, “Say, boy, you can really play saxophone. I imagine where you come from they call you mister, don’t they... but you’re still a nigger to me.” (Ornette Coleman, The Harmolodic Life) He was threatened by racist sheriffs in Mississippi and then, after arriving in Los Angeles in the early 1950s, he noted, “All Negroes that cops haven’t seen before are stopped and searched.”

Experimental Sounds in Radical Times

Coleman challenged tradition and convention and, as with so many great innovators more generally, he was constantly creating new controversy, drawing detractors as well as followers. His music, like avant-garde paintings at the time, was called abstract—seen by some as a liberating breath of fresh air, and by others as a fake and a sham. For a good part of his life Ornette had to fight to just get recognition as a serious and legitimate artist.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Ornette Coleman released more than 30 albums and he was part of, was influenced by, and impacted the avant-garde scene of radical innovations in music, art, film, and other cultural expressions. This was a time of political upheaval and struggle with big changes in people’s thinking, with young people especially questioning tradition and open to new ways of doing and thinking about everything.

In 1972, Ornette Coleman released an album of a big concert piece he had written titled “Skies of America” that he performed with the London Symphony Orchestra. I had just graduated from Berkeley High and had been swept up in the exciting tumult of the times—People’s Park, the antiwar movement, the Black Panthers. But I had also been into music as well—playing in the Berkeley High band, orchestra, and even the pit band for a performance of West Side Story. I had mainly listened to what at the time we called “soul music” and only later got into jazz because a roommate of mine was really into it.

Sometime after this, I don’t remember exactly when, I was in a record store and came across the album Skies of America. I had no idea who Ornette Coleman was, but the very idea of a symphony orchestra playing with a saxophone caught my attention. And then there was the album cover. It had the red, white, and blue stars and stripes of the American flag; above this, clouds and what looked to me like a swarm of vulture-ish birds picking at the flag. I didn’t know what the artists meant to convey but some birds were white, some blue, and the red ones looked bloody. The list of musical pieces was also intriguing, like: “Native Americans,” “Birthdays and Funerals,” “The Artist in America,” “Foreigner in a Free Land,” “The Men Who Live in the White House,” and “The Military.”

Ornette Coleman, “Skies of America,” 1972

I bought the album, took it home, put it on my turntable. I had played and listened to symphony music for years, since elementary school. But as we used to say back then, this “blew my mind.” Symphony music I had never heard before. First the full orchestra playing loud, clashing, dissonant notes, then after a while Ornette comes in with his alto saxophone—I think he’s playing a plastic one here—and it’s completely insane! It does sound like a toy saxophone, it does sound way out of tune, the rhythms are crazy. It fits right in, or I should say, clashes right in with, the whole orchestra which had been playing in a seemingly chaotic and off-pitch way. Ornette is wailing, bleating, honking. And the more he plays the more the dissonance of the full orchestra just seems to actually complement him. It is magnificent! This was right with the times—when people were not only rebelling against the status quo but also exploring and creating liberating, new things in different spheres of life.

Free Jazz and the Sound of Ornette

Ornette Coleman was a pioneer and leader of Free Jazz—as a conceptualist, as a composer, and as an instrumentalist. And he organized many different ensembles and collaborations.

He challenged and shook up principles underlying Western music, rooted in the classical music of Bach in the 1700s, and he developed a guiding principle for his music he called “harmolodics.” This was about redefining the traditional relationships in music/jazz between harmony, tempo (or rhythm), and melody. None was to be subordinate to the others. And all players were free to improvise whenever they wanted. In the liner notes for his 1960 album Change of the Century, Ornette Coleman says: “Perhaps the most important new element in our music is our conception of free group improvisation.... When our group plays before we start out to play, we do not have any idea what the end result will be. Each player is free to contribute what he feels in the music at any given moment. We do not begin with a preconceived notion as to what kind of effect we will achieve.”

This opened up new possibilities for musicians to push beyond the previously existing boundaries in jazz, became a cutting edge in the Free Jazz movement and influenced and inspired other musicians, artists, and listeners of jazz and other genres of music as well. Ornette wrote: “Music is all made out of the same notes; it shouldn’t have a caste system dividing it up.” (Gene Santoro, Stir It Up: Musical Mixes from Roots to Jazz)

Coleman would describe people playing together harmoniously, even if they were playing in different keys. While never losing the basic melody, he’d explore and replicate it in different ways, making it more complex. And he threw out the whole idea of playing fixed beats within bars of music. So sometimes his band would be playing a triple tempo, a very slow funeral-like tempo, and no tempo—all at the same time!

One might think this would be hard to listen to. But in fact, a lot of Ornette’s music was down-right swinging and toe-tapping catchy!

Some of Ornette’s detractors would accuse him of not even playing music—saying it was just abstract, formless chaos that made them want to run away. But in fact his never-done-before creations were not just free-for-alls. There was a certain framework with tension between dissonance and harmony, chaos and order, rhythm and non-rhythm, with simple melodies becoming complex. The collective improvisation, so central to his music, was part of the 1960s spirit of “free expression.” But each band member was also not just playing in isolation. They would improvise, listening to each other, responding with great empathy, finding ways to connect with all the different pieces of sound.

Ornette Coleman playing "Lonely Woman" at Jazz a Vienne 2008

And in all this there was the immediately recognizable sound of Ornette’s horn. He bent notes in a way that defied the exactness of a tuning fork. But it wasn’t just the playing out of pitch, rejection of chords, and multiple tempos. It was also the fiercely human expressions that came out of Ornette’s saxophone that surveyed a breadth of human emotions. Raw wailing, squeaks and honks that frequented the stratosphere. Beautiful tones of exhilaration and joy. Moaning and crying notes of despair. It was his very humanity transposed into sounds. Just listen to the haunting and beautiful “Lonely Woman,” Ornette’s most famous composition.

Coleman was trying to express and connect with human feelings through his music. He once said, “Some words make people kill each other, some words make people racists, some words make people fall in love. I’d like to have a sound that makes the individual appreciate who he is and appreciate others, regardless of their color, race, or religion. That’s what I’ve tried to pursue.” (1996 quote cited in Stir It Up: Musical Mixes from Roots to Jazz, Gene Santoro, 1997)

Always Exploring—“He Set a Lot of People Free”

Vernon Reid, the guitarist from Living Color, said that after he heard the news of Ornette Coleman’s death, what came to mind was a line from Frederick Douglass: “Freedom is a road seldom traveled by the multitude.” Reid said, “Ornette took the hit for being independent, for having his own ideas. Even in a genre like jazz, which prides itself on freedom, there are rules of engagement—Ornette shook up that orthodoxy. And a lot of people did not get it.... Ornette was connected to so many people and things—painters, writers, poets, the cultural flotsam and jetsam of the century, all of these giants who were connected to this iconic personage. He set a lot of people free.” (Rolling Stone, June 12, 2015)

Ornette Coleman was endlessly exploring, inventing, collaborating, learning from others, and introducing new elements to his music. In 1962, he studied the music of the Hopi Indians. In the early 1970s, he went to the Rif Mountains in Morocco to record music with the musicians of Joujouka. There were his symphonic compositions and performances in the 1970s. Prime Time, his first electric band, was a “double quartet” featuring his alto sax backed by two guitarists, two electric bassists, and two drummers, and incorporated elements of rock and influences of post-punk.

Throughout his life Ornette collaborated with many other musicians and other artists from all over the world—doing film, painting, performance art, spoken word, and dance. He said, “I really do believe though that I’ve found a way to share what I do, to inspire people to go further than what I know, to places I don’t know yet. There’s nothing in my heart that I want to hide or think if I share someone else is gonna do it better.” (Guardian, June 29, 2007)

Ornette Coleman’s last performance was at one and the same time a celebration of his life and work and a testament to just how profoundly he had inspired and influenced many different musicians in different genres. The concert, attended by 4,000 in Brooklyn on June 12, 2014, was a tribute to Ornette organized by his son Denardo, who began performing with Ornette on drums at the age of 10.

The core band for the night included regulars from Coleman’s various ensembles since the 1970s, but there were many others who came to play in honor of Ornette as well. Just to name some: there was Flea, the bassist from the RedHot Chili Peppers; jazz musicians David Murray, Ravi Coltrane, and Branford Marsalis; tap dancer Savion Glover; rock artist Patti Smith; experimental composer/performer Laurie Anderson; Bruce Hornsby; Nels Cline of Wilco; and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth. Two of the musicians from Morocco who recorded with Ornette in 1973 also performed.

Ornette Coleman's last performance, Brooklyn, June 12, 2014, with his son Denardo Coleman's band and guests David Murray, Henry Threadgill, and Savion Glover.

I was there. The evening, like Ornette, was uncommonly extraordinary. A warm summer night threatened rain, but nothing could put a damper on the tremendous outpouring of emotion that night—the powerful performances paying homage to Ornette and the audience savoring every note, wishing the evening would never end. You really felt the love and appreciation of the thousands in the audience and those on the stage for a man who had given us all so many hours of music that nurtured our body and soul with such joy, surprise, challenge and, yes, wonderful dissonance! It was exhilarating but heartbreaking to see Ornette sitting on the stage that night. We all knew he could not live forever. But we were very sure his music would go on.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.