From The Michael Slate Show:

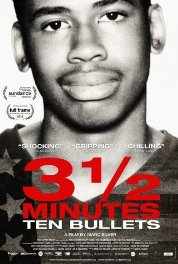

3½ Minutes, Ten Bullets—The Racist Murder of 17-Year-Old Jordan Davis

July 6, 2015 | Revolution Newspaper | revcom.us

Jordan Davis, a high school junior, was sitting with three friends in a car in a gas station parking lot in Jacksonville, Florida, when Michael Dunn, a white man, approached the car complaining of loud music. There was an argument. Dunn pulled out a gun and fired ten shots, two of them hitting Jordan and killing him. In February 2014, Dunn was convicted of secondary charges, but the jury reached no decision on the charge of murder and a mistrial was declared. In a retrial later that year, Dunn was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Ron Davis, Jordan’s father, and Marc Silver, director of the film 3½ Minutes, Ten Bullets about the murder of Jordan Davis, were interviewed on The Michael Slate Show on June 26.

Ron Davis

Michael Slate: I was deeply impacted by the film [3½ Minutes], I was deeply impacted by what I read about what you’ve been doing, what you said—so I wanted to ask you this: You’ve spoken to how Jordan’s humanity was stolen in different ways with this whole thing. People gotta understand that Jordan Davis was a high school kid. He was a young teenager who liked music, who liked life and he was full of hope, goals, ideas, and he was gunned down because of the color of his skin and the fact that he wasn’t gonna bow down and say, “yes, sir” to somebody.

Ron Davis: Yes, and I taught him not to bow down and say “yes, sir” to somebody. What happened to Trayvon Martin, me and Jordan, we talked about that. Jordan couldn’t understand why someone would take upon themselves to kill this kid for basically going to the store and buying Skittles and iced tea and just minding his own business and walking home. And so we had again that conversation with Jordan about there are people in the world—there are people in the world, they’re not just white people, you know, they’re white supremacists. There’s a difference. And people have to realize that there are people who want to go back to what they consider “the good ole days” of the Confederacy. You have a lot of people who still have grandsons that they’ve taught this hate speech to. And so I told Jordan that even though he looked like Trayvon, he has to be equipped mentally to handle these things that are out there that’s facing him as a child. He put on a brown hoodie, you know, and they have a picture of him with that brown hoodie. And this young man, I’m proud that he fought back verbally, you know. He respected Michael Dunn enough not to get out the car and try to cause harm to Michael Dunn. That’s one thing that Michael Dunn cannot lie about. Jordan never harmed a hair on his head, never scratched his car; he never did anything physically to Michael Dunn. So Michael Dunn, like the prosecutor said, he DECIDED to kill Jordan. He didn’t have to kill Jordan. But I’m proud of my son. I’m proud of the legacy that we’re going to leave.

Ron Davis. Photo: ftw

Michael Slate: Let me ask you this, because as I started to say, Jordan’s humanity was stolen in a lot of ways, both through the murder, but also in the courtroom, the whole process... In the courtroom, they wouldn’t let you show pictures of Jordan.

Ron Davis: Right...

Michael Slate: They wouldn’t let you show pictures of him interacting with his family. They wouldn’t let you show any of that stuff. But they also did something which I thought was extremely important. When they looked at him (Jordan) they almost painted—and you were allowed to see Dunn, the killer, as a human—you weren’t allowed to see Jordan as anything but a one-dimensional character whose face was simply a driver’s license ID.

Ron Davis: That’s right.

Michael Slate: You have spent a lot of time talking about the humanity of Jordan. Tell us what Jordan was like.

Ron Davis: Jordan, even as a small child, when he was in a car seat, me and Lucy remember the days when we would put on our music and drive into Atlanta proper and, you know, he would just listen to the music, no big thing. You know, he’s in his car seat in the back. But all of a sudden one day, I put on James Brown. Oh my goodness! I put on James Brown and he just started dancin’ and dancin’ and and dancin’ and we said, well maybe it was him just getting ready, you know, to dance. So maybe if we put on another song of somebody else, maybe he’ll still dance. So we put on another song and he stopped dancing. And we said this kid loves James Brown.

It was incredible. And I remember the first time we had snowfall in Georgia and I put little Jordan’s snowsuit on, took him outside and he looked at it like it was ice cream. So he picked it up, put it in his mouth and it tasted good. And he smiled and he laughed, but then all of a sudden he forgot that snow was on his hands and it started getting cold and that smile turned into a frown and I had to put his hands in my mouth to warm his hands up. You know, these things as a parent that you see, these children growing up.

Jordan liked to roller skate inside, you know, indoor roller skating. He loved to swim, he was a great swimmer. I’m a scuba diver, I’m a registered diver. And what we used to do in Jacksonville is go out to the waves right near the pier, and you’ll see it in this film. You’ll see a pier in Jacksonville. We used to go right out there. And we had a game called, you know, “Jump the Waves.” Every time the waves come you turn your back and jump as many as you can before you get knocked down. He won a lot of times. Even though I was taller than him, he still won a lot of times. So, you know, that’s a special place in that film and that’s a special place in our hearts.

Ah, my father, that was the last place he came to go to the beach. My father got sick with bone cancer. He hadn’t seen the beach in almost 20 years. When he came to live with me the last six months of his life, he asked me to take him to the beach and I took him to that same spot. So that’s a very special spot for me. It’s like three generations right there in that spot.

Michael Slate: I was very moved by the statement you made to the court after the trial was over. I want to touch on that because people don’t get the chance to actually hear what the impact is of having a child murdered, whether it’s by the police or a vigilante, having a child’s life stolen. I want you to tell people what that’s like.

Ron Davis: [Pause] The first time as a parent you get “that call,” you never forget the call. Leland, who’s Jordan’s best friend, felt blood on his hands. And Leland screamed out and called his mother on the cell phone. He was crying and screaming to his mother, and his mother called me. And that’s why—any friend Jordan ever had, I always had the phone number of their parents. I always tell parents, make sure who your kids hang out with and make sure you have their phone numbers in case of emergency. Thank God she had my number. She called me at work and told me to rush down to the hospital. The thing that a parent doesn’t know is—you hear that your son or daughter has been shot, but you don’t know if they survived. Thirty minutes of driving to the hospital, not knowing whether he was dead or alive. I never forgot that.

And when you got to the hospital, it took an hour for them to verify that it was Jordan that they had. The one thing that I tell people is that one of the worst periods of time in my life is sitting in my car when I got home from the hospital because nobody else knew but me in my family that Jordan was killed. I have to pull into the driveway and go into the house and tell my wife that her stepson is dead. Then I have to call Lucy, his mother, that her son, her only son, is dead. And I sat in that car for probably about 20 minutes, I believe, and everything was quiet. It was deathly silent. Nobody was around. There were no cars, nothing. It was just like going into a tunnel. And I had to tell these two ladies we lost Jordan. I would tell any parent out there never, ever try to take your mind to even imagine losing a child, because your brain would stop you from going that far. You can never imagine that pain of losing a child.

Michael Slate: And you still have that pain today, from what I read, in terms of even having the watch that Jordan used to have, things like that. You still have that and that’s important for people to understand, because this stuff doesn’t leave you.

Ron Davis, holding Jordan Davis' driver's license.

Photo: ftw

Ron Davis: Right. And it took me two years petitioning the court to get Jordan’s ID. I have Jordan’s ID right now in my pocket. And it took two years, because everything is evidence and everything could be overturned on appeal. So you have to also fight the court system to get that back from them, just a piece of Jordan, his last moments on Earth. I wanted his ID because it was with him when he took his last breath, and I finally got that from the court. And another thing about court is this: it’s not a trial about Jordan Davis, it’s a trial of Michael Dunn. Jordan Davis and his family doesn’t have any rights in that courtroom. You have to fight for every right that you get, so much so that the defense attorney had the nerve to put me on the witness list just to shut my mouth so I couldn’t talk to the press. He called me as a witness and the respectful thing to do is tell the prosecutor ahead of time the witnesses that you’re going to call next so you can prepare. They didn’t do that. The defense attorney decided one day, “Let’s just grab Mr. Davis and all of his grief and drag him up to this.” You don’t see it in the film, but they actually called me in the first trial to the stand—and I wasn’t even there—just to harass me as a father, and hopefully that I’ll say something to incriminate myself, and I wasn’t even there.

Michael Slate: You know, you’ve talked about going to Charleston, South Carolina, recently. And one of the things that I read that you said was, you talked about Charleston and you shared a lot with the people there; the fact that the white vigilantes did this, the same thing that was done to Jordan. But you also spoke about the commonalities of facing up to white supremacy that underlies these murders. Can you talk about that a little?

Ron Davis: When I do the Q & A’s and the film and I go across this country and I tell the audiences that I have that people that are not of color, they have also to fight against white supremacy. These are the people who are trying to tear the fabric of this nation apart. They want the good old days, the Confederate flag, what that means to them. They try to lie and say it’s about heritage. It’s not about heritage. It’s about enslaving a people, a race of people, for monetary gain. They built their whole lives and their bank accounts on the back of the slaves and they want to continue that. That’s what it’s all about. And that’s why when we had the Civil War, it was about slavery. They try to lie and say it was about everything else under the sun, but the main thing it was about was because the Southern states still wanted to have slavery and they have not gotten over that yet.

So I went to Charleston, South Carolina. Two days ago I came back from Charleston. And when I was there I called Walter Scott’s father, Walter Scott, Sr. His son was killed by getting shot in the back by a policeman. The policeman tried to put a Taser next to the body, but another policeman saw him and told him not to do that. This was all caught on videotape. This is happening in the South and happening in states across this nation. The police are using their powers not to protect and to serve but to discriminate against people of color. That’s why we need to focus on what happened in Charleston. These people forgave the shooter. That just shows you that African-Americans, over the course of decades, have been given so many injustices that have been done to them. The Tuskegee experiment in Alabama, where you were giving people of color syphilis on purpose. You know, so many things they have done to us, and we keep forgiving and forgiving. There’s going to be a point where we’re gonna stop forgiving. The white supremacists want us to come to that and have a race war. But people out there, I tell you, I think there are much more good people in this world than there are bad people.

Michael Slate: One of the things that you faced up to in particular, in relation to what happened to Jordan Davis, to your son, you talked about the way that you warned actually Walter Scott’s parents to about this, you talked about the way that there’s always an attempt to victimize the victim. And you said, “Don’t victimize the victim!” I want you to talk about that, because that’s what they did with this thing about, “Oh, it’s this kid that listened to loud rap.” They were probably trying to paint this picture of whatever, you know, “gangster rapper,” whatever, when they were talking about Jordan. You talked about, “don’t victimize the victim,” because that’s something that’s very important in terms of all this other stuff that you’ve been talking about.

Ron Davis: Right. And that’s why it’s unique, because, you know, when you have the Trayvon [case], they try to say marijuana. When you had the Eric Garner, we had loose cigarettes. We had this other Walter Scott, well, he was running away from cops, he was trying to get his Taser. It’s always an excuse, but do any of those things come to murder? Do any of those things amount to having to lose a life?

And this is what I’m talking about with Jordan. They couldn’t victimize Jordan because of the fact that Jordan didn’t have marijuana in his system. Jordan didn’t have alcohol in his system. Jordan wasn’t a gangster rapper. Jordan went to school. Jordan’s never been arrested. Jordan’s never been to prison. You know, Michael Dunn actually picked the wrong group of kids to do this to, because Jordan wasn’t all those things. I think America saw a kid and said, “You know what? That could have been my child.” That could have been my child, because Jordan was all these things that America say you have to be, you have to be that way.

Michael Slate: You’ve also had some ongoing contact with Trayvon Martin’s dad and with the parents and families of other people killed by the police. That’s one of the things that I think is really important about what you’re doing with your life now. But they do this thing where they always make it seem like even though you can testify to what Jordan was about, they do this thing where they basically end up saying, “Well, yeah, but you don’t know what he was like. He did call that man names.” Or that Trayvon, “What was he doing walking out there?” C’mon! But it’s always that thing about victimizing the victim, where somehow they try to twist it where they make it seem it’s the victim’s fault.

Ron Davis: Everything that has been happening across this nation, you have to realize that these killings, no matter whether it’s from a citizen or law enforcement, the person that’s the victim is unarmed. Why is that all the time? When is the last time you heard a national story where one of these victims was armed? Never! You know, Rekia Boyd, unarmed girl got shot in the face by a shotgun. Unarmed. Tamir Rice. Unarmed.

Michael Slate: A 12-year-old kid.

Ron Davis: A 12-year-old kid. John Crawford goes into Walmart. Guess what? Walmart sells guns. You can’t pick up a gun where they sell guns? Unarmed. He’s armed with a BB gun, you know. So all these were cases of unarmed kids. So I think there is murderous intent. There are people who are with some of these organizations that are white supremacist organizations that we found out that they’re in law enforcement. And so it’s not the blue shield any more. I think the good policemen should go ahead and pull down that blue wall and start telling on the policemen that are doing wrong. And that’s what’s breaking our country up.

Michael Slate: You know what I’ve learned over the years? One thing, the police are here not to serve the people at all; that’s not their job. They’re here to protect the system, particularly the capitalist system. They’re here to protect the system. There’s almost 400 hundred years of the most barbaric oppression against Black people. Even if a cop wants to look and say, “Hey, this is wrong,” the choice he has is to leave or become part of the machine that’s doing all of this. That’s the thing, because you’re never going to change the police. They’re not sort of misguided. They’re beasts.

Ron Davis: Well, they’re part of mass incarceration. We fight against mass incarceration. Also, with all these private prisons—and now if you look at CCA [Corrections Corporation of America], they’re on the stock exchange, where they’re making money hand over fist. And that’s why I tell them look at the 13th and 14th Amendments, when they said we abolished slavery, except in the event it’s in the form of punishment. That’s why they still have ongoing slavery—2.2 million people incarcerated and most of them, 67 percent, are people of color.

Michael Slate: Ron, on that note, we’re gonna have to wrap this up, but I want to thank you so much, man. I want to tell you that you have a lot of people, myself included, people listening to this, standing with you, man. We will be there—it’s not a question of we’ll have your back, we gotta be there on the front lines with you.

Ron Davis: Well, make sure you look at our website, which is, walkwithjordan.org. That’s our website. Go on that website and keep up with us and also see our film, 3½ Minutes, Ten Bullets. It’s out at your local theater. Please look at it.

****

Marc Silver

Michael Slate: How did you come to this story? There is a lot going on around this subject of police murder and whatnot. But you were drawn to this story. What brought you there?

Marc Silver: Well, we actually first met Jordan’s parents a couple of weeks before the George Zimmerman verdict. And at that point we spent a week with them in Jacksonville, where the shooting happened, where Jordan’s dad lived, and Atlanta, where Jordan’s mum lived. We spent a week together. We talked about what happened to Jordan, and then specifically what happened during these three and a half minutes when the two cars pulled up next to each other. At that point the reason we kind of zoomed in on this particular family and this particular story was because we saw what happened in that three and a half minutes as a kind of perfect storm of racial profiling, access to guns, and then laws that give people the confidence to use those guns.

As the film evolved and the edit evolved, suddenly all these other cases happened: Ferguson happened, and, as you know, many other shootings happened. And suddenly, that three and a half minutes wasn’t just about what happened to Jordan Davis, but it became metaphorical for what happened in all these other cases. What the film then spoke to was what was common about all these things.

Michael Slate: Let’s talk about that a little, because one of the things that strikes me is you have so many people killed by the police, so many people, particularly young Black people, murdered by the police. You think about this, and this story also brings out something that happens, as well, and probably even more frequently than most of us know. And there’s a tie between the kind of society that would condone the police murder of Black people, and a society that would condone and even enshrine laws that allow the outright murder of Black youth, Black people.

Marc Silver: Yeah. And I think for us—I can understand the sort of pundits that don’t want to make the connection or actively want to express that there aren’t connections between all of these things. But for us, I think the DNA, if you like, that was the same in all of these cases is why predominantly white men are fearful of Black men. Like, where did that come from? And particularly in Michael Dunn, where, I believe that he believed that he saw a gun. Now, clearly there wasn’t a gun. The police never found a gun. There was never any evidence that there was a gun. And I think that question of how is it that somebody like Michael Dunn can be so conditioned to think that he saw a gun like that. I think that’s a question that isn’t just for citizens, but of course is also for police in many of these cases.

3½ MINUTES Sundance trailer from marc silver on Vimeo.

Michael Slate: We’re going to come back to that in a minute, because I did want to start first with the way you told the story, which you’ve just been hinting at. You let both of these people just unroll. You allowed them to actually have the space to tell these stories. You had Michael Dunn, the killer, who got up, and he told his story. And then you had the story of Jordan Davis, who he was. And that had to be told through friends and family. I have to tell you, my first inclination would have been: Michael Dunn, racist killer. Jordan Davis, innocent youth. Now, there’s truth to that. But you didn’t just sort of heavy-hammer it on people. You allowed it to unfold. And that was a really powerful way. Why did you decide to do that?

Marc Silver: Well, I thought it was really important for as long as possible during the film for the audience to almost feel like they were members of the jury, that the information that the audience would receive during the film would be the same as what the jury received. And in that way, I think, it gives an audience a greater chance, or opportunity, to actually reflect on, if you like, their own biases. Like, could they actually see anything of themselves in Michael Dunn? And I thought rather than make him this kind of bogeyman character from the outset, there was more value for audiences when it comes to considering their own potential—whether conscious or subconscious—biases. A lot of people have said that, in a very strange way, they felt some form of empathy for Michael Dunn at points in that film. Obviously as we learn more about him, his racist views become more overt during the film, and that empathy very quickly disappears. But I think there’s great value in this idea that I believe that some audience members would, at the very least, have some feeling of connection or understanding about this idea that Michael Dunn felt fearful when he pulled up next to this car with four Black youths playing loud hip-hop. And I think the way we constructed the film allows people to question whether they would have felt that fear, and then subsequently question why is it that they feel that fear.

Michael Slate: Then it draws them in. As things turn around and you listen to—a brilliant move, that thing about the phone calls. That was incredible. I want you to talk about that, because that actually allowed him to basically lay out all of his ugly crap.

Marc Silver: Yeah, it was very interesting, because we couldn’t get access to Michael Dunn, in terms of an interview with him or his family. They didn’t want to be in the film. But we did have a kind of variety of other jigsaw puzzle pieces, so to speak. So one of them was the initial police interview that was done with Michael Dunn about 24 hours after the shooting. And because in the state of Florida, we were able to access Michael Dunn’s phone calls from prison, which are all recorded, to his fiancée Rhonda Rouer. We started listening to these phone calls, and, again, they were hugely revealing in the sense that Michael Dunn never believed that he did anything wrong. And he frequently expressed this in these phone calls. So perhaps, actually, it worked well for the film that we weren’t able to directly interview him. In a way we got something that was much more honest by hearing these phone calls between him and his fiancée about how he felt there was a major wrongdoing in that he was even being charged with this crime, because he so firmly believed it was a case of self-defense.

Michael Slate: What becomes clear in that whole series of telephone calls, he allows all this. He just flowers, in a certain sense. You really see the internalizing of all this racist stuff that’s in there. The idea that he even talks about “good citizens” and he talks about the idea that basically if he hadn’t killed Jordan Davis, then maybe Jordan Davis would have gone out and killed somebody else right after that. You’re watching it and you’re thinking, “What the hell?”

Marc Silver: Incredible. Yeah, he believes, I think, that he saved other people’s lives by killing Jordan Davis. There’s another incredible line by him, which, when you’re in the cinema, you always hear a gasp from the audience, that he compares himself to a rape victim who is being blamed because she was wearing a skimpy short skirt or something. But what I found most interesting about those types of comments was the way that Michael Dunn almost became a metaphor for parts of America being blind to their own racism. That’s why I felt that Michael Dunn was such a powerful character in the film. Obviously what’s on the surface as he’s giving testimony and all of his phone calls and his initial police interview, but much more deeply, I think he came to represent something much more powerful.

Michael Slate: A lot of people talk about this. And you made the point that race itself was not allowed to be in the courtroom. It was present in the courtroom anyway, but it was also present in the streets. But there was a thing that was going on as well, which was really very heavy. You have this whole thing of the description, especially by white people, as the “loud music trial” or “the thug music trial.” But it was all about some kid who played his music too loud and that’ll teach him—and it deserves death. And that strikes deep in your heart, because you’re thinking, what the hell is this?

Marc Silver: Yeah. There’s a scene in the film where we hear voices from people in Jacksonville who are calling into a radio chat show and someone actually says that, “Why was this even called the ‘loud music trial’? Why wasn’t it called the 21st century lynching trial?”

Michael Slate: Exactly!

Marc Silver: Powerful words. And this idea that race wasn’t allowed to be discussed in the courtroom, so that was in some pretrial hearings, the defense lawyer had basically said that because Michael Dunn wasn’t charged with any hate crime, because he wasn’t heard using any words of hatred when it came to race, that race was not allowed to be discussed in the courtroom. And on top of that, Jordan Davis was not allowed to be called a victim during the trial, because by calling him a victim, it would have implied that Michael Dunn had done something wrong, and that would have altered the jury’s mind. Obviously, as I realized that there was this massive juxtaposition between how the case was discussed inside the courthouse, where there was no mention of race, and then on the streets outside and on the airwaves of Jacksonville, everyone obviously was perceiving this as this never would have happened if this was a car full of four white teenagers that Michael Dunn had pulled up next to.

Michael Slate: And that challenge to people who were following the trial, who were actually looking at it, and the challenge to people who view your film now, in terms of even the television coverage from inside the courtroom, which again was also astounding, and really refreshing—and important because it allowed that to unfold. You had to deal with that thing of Dunn’s sense of entitlement and his claim to be “a fine upstanding American.” He says, “Hey, I’ve got a good life. I live on the beach. I’m an engineer.” And on the other hand, this Black kid, whose story is only really told, and it’s told very powerfully, by the testimony of his friends, both in the courtroom and outside, and his mom and dad. And they’re the people that are just laying their hearts out and saying, wait a minute, we’re human. And it was those two poles: No, they’re animals that deserve to be penned up and killed if they threaten us, and then, no, we’re human. Very powerfully posed.

Marc Silver: I think that it’s very important in films that are about inequality and human rights that we try to decrease the differences between people and try and break down these constructions of otherness and race so that we can see each other just simply as human beings. And Ron and Lucy, Jordan’s parents, that’s how they wanted to bring Jordan up, and how they did bring Jordan up. And I think in the way that they speak since his murder, they’re almost still parenting Jordan in his absence. And I think one of the things we tried to do was, how do you show who Jordan was, given that obviously we never got to meet him? And you get to learn who Jordan was in his absence through understanding who his parents really are, who his friends were who were in the car with him, and also his girlfriend, who happened to see him that night for the very last time. And through meeting all these other people who obviously surrounded Jordan when he was alive, you get to realize that the impression you get of Jordan from Michael Dunn couldn’t be further from the truth.

Michael Slate: And what they learned, too, what all his friends learned, for instance. Who was that young man talking about the loud music question? He said "they called it 'thug music,' and that’s simply another word for calling me an N_____." These days, it’s acceptable to do that.

Marc Silver: Yeah, absolutely. I loved hanging out with his friends, because they just told it as it was. There was nothing academic. We didn’t speak to any specialists on race or anything like this. We just spoke to 17-year-old boys who understood that there was a certain sector, if you like, of society, that felt that they should be presented in a certain way, and they were having none of that. Even when Michael Dunn, on the witness stand, claimed that he never used the word “thug music,” and he called it “rap crap,” one of these boys just ripped that apart and just said, “Rap crap. He made that up when he was in prison, because he knows now ‘thug music’ has certain connotations.”

Michael Slate: Marc, your heart had to break at the outcome of the first trial, where there was a partial mistrial. And you’re looking at and you’re thinking, how did this happen? But then I realized, one of the things that you’ve done in there is that through your camera and the focusing on the trial, and the way you said you wanted the audience to actually be jurors, you also had to deal with the fact that you painted a picture of an entire society that’s built around this, and that allows it and accepts it. It accepts this kind of judgment, accepts this kind of view of Blacks and other people of color.

Marc Silver: Yeah, you’re absolutely right. I was just thinking while you were saying that, I remember being in Jacksonville and thinking a lot about The Wire, and how the different series of The Wire looked at a different structural element, the media, or education, or race, and how when all of those things come together, we start to understand maybe like a wider perspective on things.

But in many ways, yeah, when the first verdict was declared, the tragedy is that standing there in the courtroom when that happened, I’d like to think I couldn’t understand how that actually happened, but the tragedy was I could understand, because the system inside the courthouse was set up in such a way that if race isn’t allowed to be discussed, that’s one thing. But watching the defense lawyer and the prosecution do their thing over a couple of weeks in court, I realized that actually, it was very ironic. The Seal of Florida was above the judge’s head, and it says, “In God We Trust” on the Seal of Florida. And I looked at that at times, and I’m watching the defense and the prosecution express themselves, and I thought, you know, I’m not so sure this is about In God We Trust, rather than it might actually be “who tells a better story in this courtroom is going to be the winner.”

And watching the defense lawyer, I can absolutely understand, he was so good. All he had to do was sow enough reasonable doubt in the minds of the jury that of course it was going to lead to a mistrial. And I think he was extremely successful. He didn’t succeed in the sense that Michael Dunn was found not guilty, but I think given the circumstances, he totally did the best job he possibly could, and sowed enough reasonable doubt in that jury’s mind that it led to a mistrial. When you start understanding a system in that way, yeah, I was tragically not surprised that that was the verdict.

Michael Slate: Yeah, it’s an important point. And it fits with this thing I was just thinking about, because there’s this element of how you also revealed through the contrast and the interplay of both sides with what was going on, you revealed the nature of the entire society. I was telling you a little earlier about the Border Patrol being exonerated from all these shootings on the border of totally innocent people, kids throwing rocks, and it was OK to do that. And the same thing that actually happens here, you see this in the trial. It was not that far removed from the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin, this whole idea that this is the right of the good citizens to stand up and just have to hold on and do what they can to keep things under control. And it reminds you, seriously, that there are too many “good Germans” in this country who refuse to stand up and recognize what’s going on or say anything. There is, society-wide, a kind of fashioning of a foundation for this kind of fascistic wing in society.

Marc Silver: Sure. And it’s branded as democracy and freedom. It’s like fascism with a smile sometimes. Once you start looking at all of these elements, you understand that this kind of brand identity of post-racial America is clearly not the case.

Michael Slate: The idea of Stand Your Ground, which was another really important element in the film, and in the case, the idea that they didn’t have to prove anything other than he believed all this—and he did believe all this. He believed everything he had conjured up, which doesn’t say what he did was right or excusable, but when you look at the system, that says that’s enough to get an innocent verdict.

Marc Silver: Yeah. And obviously that prompts a question about how is it that people are conditioned to get to a point in their lives where they are capable of believing that? And I think that is the bigger question of the film, and why the film connects to all of these other shootings that have occurred.

Michael Slate: And it’s heavy, because you’re sitting there watching this and you’re thinking, he actually believes this, and there’s an entire society that believes this. After Trayvon Martin, after the verdict in the Zimmerman case and the murder of Trayvon was completely whitewashed and allowed, and then the string of murders happens. And then you have Jordan Davis, and the trial goes on. You have Ferguson erupt. You have Eric Garner in New York, who’s just standing there screaming, “I can’t breathe” as cops are filmed strangling him. And you think of all these people saying, I believed he was going to hurt me. I believed he was armed. I believed this, I believed that. And it’s not just justifying individual acts, it’s justifying the whole view.

Marc Silver: It’s funny, when you speak about the whole view, there were points in the edit, I remember with the editor about halfway through the edit, where I suddenly realized that, you’re right, the film is a metaphor for much bigger things. We were talking about weapons of mass destruction, and this idea that Michael Dunn’s lawyer was criticizing the police for not doing a good enough job by not being able to find the gun. And there was a moment when I thought about weapons of mass destruction and the fact that it’s almost the same kind of thinking at the individual level of what Michael Dunn said about essentially fearing the other and shooting in self-defense, in a preemptive strike so he wouldn’t have got hurt himself, was not so dissimilar to going to look for weapons that don’t exist in another country, shooting in self-defense and being scared of these other people that we don’t understand.

I understand that that’s a metaphorical leap, so to speak, but in my heart, I feel there are connections between Michael Dunn as an individual, and we could take it all the way up to U.S. foreign policy. And I think that’s very interesting when you can make a film about essentially what happened to one family, in a very kind of micro-forensic way, as it is, as we follow this trial, but actually in your heart, you start feeling that this is connected to much bigger things.

Michael Slate: They actually do—they have this sense of entitlement that the world is theirs to conquer and hold onto, when you think about the imperialists that run this society and try to rule the world—and pretty much have ruled the world for a long period of time. They have no problem going and overthrowing governments, drones taking people out all the time, all these kinds of things happening, because they view it as their world, and what they say goes, and there’s “us and them.” And it’s a very heavy thing, because that’s what the foundation for what happened to Jordan Davis was.

Marc Silver: Yeah, absolutely. And I guess that’s what I’m trying to highlight or bring attention to, or inspire people to just look at that kind of construct from a slightly different perspective or angle.

Michael Slate: What did you think when the verdict came in of not guilty, and then there was a retrial a short while later, and the verdict came in as guilty? And you’re looking at this guy, and you could see Michael Dunn was stunned. He’s going to spend the rest of his life in prison. You had to wonder, what really changed? I don’t get the sense that it was so much what changed in the courtroom as what was going on outside. What do you think of that?

Marc Silver: Two things. Ferguson happened in between those two trials. I’d like to think that perhaps the second jury had been affected by what happened in Ferguson, and actually did think that Black lives do matter and that had shifted their perspective, that they sat through that trial and they came to the conclusion that clearly he was 100 percent guilty. Unfortunately, that perspective is slightly warped by the fact that in the second trial, Michael Dunn didn’t have the same defense lawyer. And I think that perhaps the second defense lawyer was maybe not as good as the first defense lawyer, and that second lawyer wasn’t able to sow as much reasonable doubt as the first lawyer had. But obviously I prefer to think that maybe that second jury, their views were more evolved than the first jury.

Michael Slate: Jordan Davis’s dad, Ron Davis, said that Trayvon Martin’s father called him and left him a message that said, I want to welcome you to a club that none of us are happy to belong to. Let’s talk about that a little bit.

Marc Silver: It’s a very powerful moment in the film. And actually, even when Jordan was alive, when he saw Trayvon’s picture on the news, he turned round to his father and said how similar he felt he looked to Trayvon, and obviously how prophetic that turned out to be. And since this happened to Ron, Ron has subsequently gone to other families and welcomed them into this club that no parent wants to be a part of. And again, of course, this is a massive thing that I would imagine that most, if not all, Black parents have to have this kind of conversation with their children at the moment. And even if they’re not having the conversation with their children, their children are seeing representations of themselves on the news and seeing how dangerous it is at the moment to literally be Black, and that’s a massive conversation that America should be having with itself.

Michael Slate: Absolutely. And I’d add just one thing, because I think it’s extremely important what you just said, that whole point that we were talking about earlier, about people thinking it was OK to tolerate this stuff, and how that has to stop. When the film premiered at Sundance, and I know you were nervous about how it was going to be received. But then when it was over and [there was] a standing ovation, and then you had Ron Davis come up, it was a large enough theater, and it ran through your body. There wasn’t one person in the house sitting there going, “meh.” Everyone was really taken by this. And then Ron Davis gets up and he starts agitating about how this can no longer be tolerated, and he calls on people to put their hands up, if you’re going to stand with him, if you’re going to be out there fighting to end this, if you’re not going to tolerate this any more. And there wasn’t one person that didn’t put their hand up in that house. I thought that was a really moving moment. It seems that there is this kind of movement that’s started to grow, and I was wondering what you thought about that.

Marc Silver: I will likely never forget that moment. Also, it’s very important because of the type of people that were in that audience. I think Ron mentioned recently to me that he was on a march in New York City, where about 60-70 percent of the people on a Black Lives Matter march were white. And again, I think this is a film for white audiences to understand or be invited to reflect upon their own biases. Because this isn’t just going to change by Black people saying that Black lives matter. It’s actually white people that have to understand their own implicit biases and racism, conscious racism and subconscious racism, in themselves, let alone how that manifests throughout the whole system.

Volunteers Needed... for revcom.us and Revolution

If you like this article, subscribe, donate to and sustain Revolution newspaper.