Hundreds Trace the Path of the 1811 Slave Rebellion in Louisiana

Artist Dread Scott interviewed on KPFK's The Michael Slate Show

| revcom.us

The Michael Slate Show on KPFK Pacifica radio airs every week at 10 am Pacific Time on KPFK 90.7 FM in Los Angeles, a Pacifica Network station. Revolution/revcom.us features interviews from The Michael Slate Show to acquaint our readers with the views of significant figures in art, theatre, music and literature, science, sports, and politics.

Michael Slate: In 1811, 500 slaves in southern Louisiana rose up in a rebellion that could have changed history, but very few people today know about this rebellion, and even fewer know the truth behind it. On November 8 and 9, hundreds of reenactors will retrace the path of the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history. And here to talk with us about it is Dread Scott, an artist who has spent the last six years or so working to bring this rebellion alive again. Dread, how are you, man?

Dread Scott: I’m doing good, doing really good, and thank you for having me on.

MS: I look forward to having you on for a lot more around this cause. I’m sure there’ll be stuff to talk about after you’re done, too, this week. But let’s look at this. Very few people know about the rebellion, not to mention the significance of it. So let’s start with what it was and why it was and remains so significant.

DS: Yeah, well, in January of 1811 the largest rebellion of enslaved people in the history of the United States happened. That rebellion didn’t happen because one enslaved person got whipped one too many times. It was actually planned for a year or maybe longer, and they had this bold vision to seize all of Holmes territory which is now modern-day Louisiana and set up an African republic in the New World. It would have been a sanctuary for Africans and people of African descent, and it would have abolished slavery much the way it was done after the Haitian revolution. It was the most radical vision of freedom in the United States at the time and was also more radical than the French colonial society, which, even though they had the Declaration of the Rights of Man, was a slaving empire. So the significance today is, here was the largest rebellion of enslaved people and it had a vision that was gonna actually really remake and change world history by eliminating enslavement in the locations where they were hoping to seize power.

And the other two things that are important about this are that it actually had a chance at success. All slave revolts are a long shot. But this was actually planned in a way that it could have succeeded. And then the other thing that is significant is the history of this is buried. It’s completely suppressed. It was suppressed starting from day one. The governor spun the story that there wasn’t much to see here. And then, when they started doing more scholarship and research into slavery, because the original knowledge was suppressed, and it was said there was nothing significant to it, a lot of scholars didn’t pay that much attention to it. And really, the modern history, and modern telling of it, only became more widely known when a people’s historian published a book in 1996.

MS: You know, one of the things that really got me, and I was talking with my friend here, and he was wondering how much Haiti had actually influenced the rebellion in Louisiana.

DS: Yeah, there are several ways which it does, and I will put a disclaimer on this and a lot of other things I might talk about, about the history. I’m an artist. I’m not a historian. And historians have done work on this and it needs to have more historic research. I can tell you what I know, and I’ve studied a lot of history and worked with historians, but I’m not a historian. So, what I do know is that part of why sugar was even being grown in Louisiana was because of the rebellion, the revolution that was successful in Haiti. When the revolution jumped off, a lot of the enslavers decided they had to get the hell out of Dodge because the revolution was gonna overthrow their economy, but also potentially kill them. And so they fled. Many went to Cuba, and many went to Louisiana. And so that was part of the reason why the people that had the desire to grow sugar, but also the people with the knowledge of growing and refining sugar, and that was enslaved people, because the enslavers when they left Haiti, they actually brought the people they enslaved with them. And producing sugar is actually complicated. I mean, the skill necessary to refine it is not something that everybody knows how to do even back then. And so they needed people with the particular knowledge of doing that to be able to set up more slave labor camps that were plantation agriculture at the time.

Another thing is that Haiti was the largest producer of that particular commodity in the world. And after the revolution, production dropped drastically. They didn’t want to be part of the world economy of sugar production in the same way. And so that meant that there was a gap. And if you’re a capitalist looking to make profit, you’re like, OK, this commodity, we need more of it and we can grow it elsewhere. And so, that led to sugar being more grown there, but then when you bring enslaved people with knowledge of this incredible revolution that happened in Haiti. They all started thinking, well, maybe we should do that here. And so there was an inspirational aspect and aspirational aspect, including possibly that some of the people that were in Haiti might have even participated in the rebellion. And here’s where there’s a conflict between historians. Some historians say that the leader of the revolt in 1811 in New Orleans, Charles Deslondes, some say he was born in Haiti, and some say he was born in Louisiana. And I don’t know the difference. I mean, I actually don’t know what’s true. But it is conceivable that this was a person that was Haitian born and thus brought some of his knowledge of that revolution with him.

There are a couple of other factors that go into why this rebellion was in Louisiana, including that the United States had recently purchased Louisiana. As various rising capitalist powers do, they bought Louisiana from the French, from Napoleon. And part of why that happened was that with the Haitian revolution, Napoleon didn’t want to send his large admiralty around... halfway around the world because there was nothing to defend. And so in addition to having war debt in the war that he was fighting in Europe, he didn’t need to have a place to kind of refine some of the sugar and grow crops, so he was willing to let Louisiana go and so the U.S. was taking over. And so there was serious in-fighting, and differences, and changes in power that weakened the various ruling classes that were there in Louisiana at the time. And so the enslaved thought that they actually might have a shot at successfully wresting a bit of territory and freedom out of that situation.

MS: One of the things that got me, and the work that you’ve done on this in terms of really digging up the history, which in a lot of ways... I could tell from reading some of the stuff that you put out... there were people who you could go to who knew some of the history—some of them knew more, some of them knew less—but it gave you something to actually work with. And it really was, when you look at this, the important element of actually looking at the actual history of this rebellion, and that it was in fact suppressed. Even the name was erased from history and changed to what, “The German Coast Uprising of 1811,” which would give you no hint about the significance of this rebellion.

DS: Well, the German Coast uprising enters at the development of empire and state and stuff. Many Germans came and settled in that region, the region where this rebellion took place in part of Louisiana. And at the time, it was a Spanish colony, that region. And so the Spanish said you all can live there. And then most of the Germans left or died out. There were still some there in 1811, but largely with the importation of Africans, it had become a coast that had slave labor camps and had enslaved a lot of people who were principally Africans. And so it might be better to call it the African Coast Uprising, but the main thing is that it has become known as the German Coast because Germans were settled there in I believe the late 1600s and early 1700s. But then it doesn’t even get... even if you call it the African Coast Uprising, it doesn’t really get at the majesty and the significance of what this is. Other rebellions are often known as Nat Turner Rebellion, Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey, and you’d want to look into this. And this is just named after some geography that is meaningless today. People in this region don’t really call it the German Coast. Some would, and some would know that, but largely, that name has fallen out of history because this rebellion actually is not significantly acknowledged and remembered. And this rebellion again could have changed U.S. and world history. And even more than the capacity to change history, here is a story where enslaved people organizing that together with more than 500 and had this bold vision of freedom. That’s the story here. That’s amazing, and people who care about humanity, and care about the development of the world, and how it got to where it is, I mean it’s both a “what if?” question. What if it had succeeded? But it is also a question if we just want to know history, this is something that is really significant and that should be known, and all students should know in part because these leaders were heroes. Instead of studying George Washington, a great enslaver, or Thomas Jefferson, a great enslaver, when they talk about freedom we should be studying people who were actually trying to get free from a system of enslavement, which was the foundation of the U.S. economy at the time.

A Hidden, Repressed History

MS: We’re talking today to revolutionary artist Dread Scott about his latest piece of work called Slave Rebellion Reenactment.

It’s very heavy just reading the things that you’ve put out in relation to this, where you talk about what you are doing and why. And there is so much here to be learned that so many people haven’t learned because it’s been actually hidden, it’s been repressed history. The whole idea that people got up there, and that the motive for the rebellion wasn’t just to go out and raise hell, but it was to end slavery and nothing less than that. That they wanted a whole different society ... and that was a huge threat to the institution of slavery overall. And in a lot of ways, repeating that truth could be very, very dangerous today as well.

DS: [Laughs] I hope so. This is a country that was founded on slavery and genocide, and it continues to be based on exploitation and oppression. If I ran a society that was based upon the stolen wealth and suppression and violence and brutality, the stolen wealth from Africans and people of African descent, Black people in this country, I surely wouldn’t want people broadly to know that there was this major attempt at overthrowing and overturning that system. That might be inspiring and it might have implications for today.

And so this piece is actually about mining this past, and that’s really important that people should know that. And in conversations I’ve had with youth, particularly those from historically Black colleges, I get a sense of how important actually knowing more about the actual history of this past is, but it is also a piece about the present. I mean, a lot of my work looks at how the past sets the stage for the present, and how it exists in the present in new forms. And this history of rebellion and self-determination and agency of people trying to get free to overthrow systems of oppression is something that people in the present should learn from. This is not a project about slavery, this is a project about freedom and emancipation. What would it mean if people actually drew inspiration from those people who identified that the problem was that they were enslaved? That was the problem. The solution was to end slavery. Not like lessen slavery’s chains, not just get whipped Monday through Friday, not form a Super PAC, and try and write some legislation that modifies slavery. But they wanted to overthrow the system of enslavement. And people today can dream about changing some very fundamental things about the system. I think that’s where a lot of space and imagination gets opened up by this project. Even on questions that... I just recently learned that a somewhat well-known family member of somebody who was killed by the police is getting on a plane to come out and participate in this reenactment. And so for them to actually look at the history, and look at it through a lens of trying to look at how people fought back, that’s actually really important. And then of course some people may draw lessons that what we need here is a revolution. And I think the possibility of that is opened up by this project.

MS: Now I want to just return to this a little bit because it really strikes me as we’re talking, that this whole point that the whole motive for this rebellion being to end slavery and nothing less... that they wanted a whole different society. And that was a huge threat to the institution of slavery overall, and to the coming into power of U.S. domination in the whole area. This was something that could not be allowed, it seems, in relation to what that slave rebellion could mean for the rest of the world, for the rest of the country.

DS: I think that’s true, but then there’s also sometimes things that can’t be allowed to happen. If Napoleon had his way, Haiti would have been drowned in blood. But the Haitians, the people in Saint-Domingue that formed the nation of Haiti, were successful. They beat the strongest power in the world at the time. And if this rebellion were successful, it certainly would have put, not the final, but put a nail in the coffin of the system of slavery. But it’s a question of how would the U.S. have responded if there were a free African Republic right on its doorstep. America didn’t initially say invade Mexico to rip off Texas. Texas ended up seceding from Mexico and they did it so they could expand and preserve slavery. That’s part of the irony. But the U.S. didn’t have total freedom to do whatever it wanted. And so if this is successful, it’s conceivable that the U.S. might just have had to tolerate a free republic on its doorstep. Again, I’m not a historian, and there might have been a million reasons why they would have wanted to invade. But the country was not settled as we know it today. And that’s part of what I think is important about looking back at the history. The past was not pre-determined, and neither is the future. And so the aims and goals of this rebellion were something that could have really vastly changed what was occurring than it did. And as you say what these people were aiming for, overthrowing the system of slavery, was something that was irreconcilable with much of what the growing United States was trying to be. And so it would have been a very sharp rebuke and challenge ... if it spread, would other enslaved people in other regions of the South have said, “Hey, we should do that too” and overthrow the system of enslavement? Would that have happened, or would it be something where the U.S. would have to act and try to reinsert itself? And that’s I think what is an unknown. ’Cause even at that point the U.S. was also fighting the Spanish in west Florida, you know, which [today] is modern-day Mississippi. So that region was very unsettled even by the European powers, and then there were all sorts of different Native peoples that lived there, and were there long before the United States, the British, the French, and the Spanish were. And so it is a potentially volatile mix which could have spun in lots of different directions. And actually, even on this question of Native population, while this was predominantly a rebellion of the slave people of African descent, there were Native people—some of which were enslaved and some of which were just in the region—who joined the rebellion. And so there’s potential alliances of various oppressed people to take on colonial powers, there’s a lot of potential and excitement there.

Disciplined Army of Slaves on a Freedom March

MS: You know, that’s one of the things that I thought was really important about what you’re doing here. And the fact that rebels were tried and executed on the very plantations that they overthrew, their heads were decapitated, their heads were put on poles, there was a whole message sent out to people that was saying don’t even think about this. And yet the heroism of the... from what I’ve read in what you’ve been putting out... the heroism, the staunch belief in the need and the right for people to rebel against this horrifying situation, and to establish their own living, and their own ability to live and to flourish. This is something that I think really gets lost for people a lot of times. That it’s not like these people, who had no real sense of what they were doing, they were just like out to just burn and pillage. They were actually people who were saying we can no longer live like this. We refuse to live like this. And they stood up and they became a disciplined army of slaves. That was actually something I thought was really important about what you’re portraying in the piece that you’re doing now. You’re portraying a disciplined army of slaves on a freedom march, actually.

DS: Yeah, this question of discipline has a lot to do with how people see this period and whether it was just again people striking back. Let’s be real. People who were enslaved on a sugar plantation, life expectancy was seven years. They were literally working people to death. The commodity of sugar was so valuable that they could basically work people and have them die and get more people to replace them. And so there was a strong incentive for individuals to run away, which happened a lot, to strike back as individuals, to run away with a few friends, and form Maroon colonies. And there were several Maroon colonies in the area. This was not that. This was something where people wanted to overturn the whole system of enslavement. And that’s something that should really, really be known. And so there is a point of how were they trying to do that. We don’t know a lot about this history because the only people who really tell it are enslavers. A lot of the record that it is based on is the so-called tribunals, or trials, where they were basically torturing people saying, look, we’re going to kill you anyway, so the only real choice you have is whether we randomly kill a lot of your friends and family, or whether you rat out all the people who participated so we can kill them too, and then we’ll let some of your friends and family live. And so these were tribunals under a great deal of duress. And some people courageously stood up and said exactly what their aims and goals were. But others had... there were different stories, but a lot of this is assembled... the knowledge of what people were attempting is based on trial transcription and few other records. But the thing of how we know they were a disciplined army, is that the U.S. generals, and General Wade Hampton wrote to the governor, Governor Claiborne, and said there are 500 brigades in the field, and they’re marching in formation under flags, and so they didn’t record what the flags looked like, but it was saying, look, we’re fighting a disciplined army here and this is people’s war. It was an uprising. The enslaved could not form companies and stuff beforehand. They couldn’t practice with the weapons that they were seizing in advance. But they knew... some of them were from regions of West Africa where there were civil wars. So many of them... or some of them probably had training in guerrilla tactics and civil warfare. Others of them had been seeing the militia for the planters trained. And others of them might not have ever been in a battle or seen a battle, but knew they had to fight for freedom so they grabbed a... if they couldn’t get a musket or a saber, you grabbed a machete. If you couldn’t get a machete, you grabbed a rock or an axe or a hoe, and farm implements. But it was disciplined. The generals are saying, hey, these guys are forming regiments or companies and they’re marching under flags. I want to actually show that, because it actually changes how modern-day people look at that period, and look at how Black people organized with the possibility of getting free. Were people just randomly striking back, which would have been just and righteous? Or were they looking like they had a plan to get free, and doing everything they could to execute that plan, even if the military strategy which they were going to employ would much more rely on guerrilla warfare and knowledge of the swamp and not wanting to get into a head-to-head battle, and fight for the tactics that British colonial powers fought in.

And actually if you look at some of the history of the Haitian revolution, the French were furious and bedeviled that the enslaved wouldn’t just stand in a neat line waiting to be shot. But they had the audacity to hide behind trees, and things like that. So the military strategy that was employed from different armies working for different aims is something that will get expressed in this artwork, but it is something to take note of that we want to challenge and change how people see what Black people in what is now America acted and behaved at that time.

The Slave Rebellion Reenactment—a Work of Art

MS: One of the things that you also talk about, you talk about the disciplined army of slaves on a freedom march, and that you’re actually doing the actual march, the actual route that was taken by the slaves. And I kept thinking about that as I was reading this because there’s like that sense of (and I’m not trying to be all weird about it) but there is this sense of the people, the feet of the people, the blood of the people in that same area, that same route that you’re marching through. And you have all that going on, and then you have this message to the people, where the march will be that you’re putting out, and I thought this was very heavy. I read that you said that the rebels of 1811 would have been fighting for people like you, and basically posing to people the question of “So what are you gonna do?”

DS: Yeah. So first, let’s give your listeners a bit of a sense of what this is, cause we’ve been talking about the history, but we haven’t so much talked about what the artwork is. And so Slave Rebellion Reenactment is going to reenact this rebellion, the largest rebellion of enslaved people in the history of the United States. And so we’re going to have hundreds of reenactors in period costumes with machetes and muskets and sickles and sabers. We’re going to be marching for 26 miles in locations that were sugar plantations that are now oil refineries, and Pizza Huts, and grain elevators, and gated communities, and trailer parks and strip malls. It’s exurban New Orleans. And we’re going to be marching, chanting, “On to New Orleans! Freedom or Death! We’re Going to End Slavery. Join Us!” There are gonna be beautiful flags flying. They aren’t gonna be U.S. flags. They are going to be flags that we imagine that enslaved Africans might have made to rally their courage and to fight underneath. We will draw on tradition that would have been popular for people in the region at the time. There will be singing. There will be banging rocks on machetes. A drummer, there’s a traditional African drummer who is providing some of the rhythms for us. This sounds like war. So it will be a beautiful procession and largely it is a freedom march. There wasn’t actually a lot of fighting in this rebellion until the rebellion was put down, and we’re not reenacting that. We’re not actually depicting the slaughter of a lot of Black people by white people. We’re actually interrupting the historic timeline. And when we get as far down river as the rebel army got, we are going to get on buses and go to a location in the city of New Orleans itself which is now the old U.S. mint, but in 1811 was Fort St. Charles. There was an advanced detachment of enslaved people in 1811 who were trying to seize that fort so that when people got out of the slave labor camps also known as plantations, and got down river, they would have enough weapons to seize the city. So we’re gonna honor this sort of battalion that was trying to seize this fort. We’re gonna march past the old U.S. mint. We’re gonna go through the French Quarter and end up in Congo Square. And when we get to Congo Square, we’re gonna flip from a military campaign to a cultural celebration. Congo Square and a few places like it are vital to the preservation of the rhythms that became foundational to what we think of as American music. There are a couple places around the country. Congo Square was one of them where the rhythms... where people were allowed to gather and dance and play in traditional ceremonies and rhythms and songs that they did back on the west coast of Africa.

And so, that laid the foundation for jazz, but then of course blues, rock ’n’ roll, rhythm ’n’ blues, funk, disco, hip-hop, bounce, trap, trance... none of that would exist if it weren’t for Congo Square and places like it. There we’re gonna have, in addition to lifting up the names of the rebels that should be more known, we’re gonna have a musical celebration of all that is created by having this culture present in America.

And so, this is this amazing freedom march, that didn’t have a lot of fighting. There is a little bit of fighting that’s gonna happen. And we’re gonna reenact a skirmish that happened so there’ll be musket fire and horses charging around and it’ll be really, really cool. But the thing for people to understand is this is Black people moving in outdated French colonial 19th century clothing past grain elevators and oil refineries and Pizza Huts and gated communities. It’ll be a clash between that past and the present, kinda. And in that space, I think a lot of people can really learn a lot and rethink both the history of enslavement, but also the history of people fighting for freedom.

MS: One of the things again that really keeps striking me... I gotta tell you, man, every time I read something about it, and looked into what you had produced around it, I was really moved both by the history but also by what’s being posed for people today. And the fact that when you brought people into this, it seems to have had a very big impact on people. People creating their own costumes, figuring out other ways to actually help push things forward, people coming to you and saying, look, I want to be a part of this. This is an extremely important development, I think, in the basic situations that we’re living in today because you had six years of preparation, and a whole community has gotten involved in this, and at the same time, they relied on what you had, but they’ve also developed these groups that you’re talking about, figuring out ways that they can contribute. And I think that’s really important, both for people understanding what was the significance of what happened and what’s the significance of what’s happening today, what needs to happen today.

DS: This thing about this being for people today, you mentioned something I said earlier about saying the 1811 rebels were fighting for people like you, well, one of the things we’re marching past is a steel refinery, a steel plant that’s been closed. So like 300 or 400 people were kicked out of work. I’d like to think that those people would view the spirit of 1811 is something they should be taking up and fighting not just for their job in a narrow sense, but actually to get to a world where people are not mistreated as something that is valuable if they can produce profit for somebody else. And so people on that basis and others have actually been coming to this. The people who participated in making costumes, either for themselves or other people, a lot of people, the army of enslaved is only Black people and indigenous people. But lots of people of all ethnicities including white people have helped make the costumes. The costume designer is white, and she... we encouraged the people, particularly like the costume designer, to reach out beyond their traditional circles where she would have spontaneously gone to find other seamstresses to see if she could find some Black seamstresses. And she did. And so it’s been a really productive conversation for her, and then the people that are coming to volunteer and work with them collaboratively, and it’s been really, really meaningful. I’ve been to a couple of these sewing circles and people were talking about the importance of the artwork, but also why it matters today, not just for something simple as ending racism [chuckles] or undoing racism. But for... when people then start very quickly go to, “Well, the police just murdered a woman in her home in Fort Worth.” You know, a woman who is just sitting in her home... somebody called the cops, foolishly I might add, for a welfare call and the cops show up and shoot the woman through her window. That’s the world we’re living in, and I think a lot of people are drawing connections between history of enslavement and how people are treated today, and then hopefully the history of freedom fighters and how people need to get free today.

I think some of these relations of the people kind of walking in these shoes, both in the footsteps, ’cause it is going on the locations that this rebellion actually happened, but more metaphorically in the shoes of people who really had nothing to lose but couldn’t continue to endure enslavement until they died in seven years, but said no, we need to get free. It’s a long shot, and we all may die doing it, but let’s actually do something that actually has a chance of liberating us. And so those ideas are really meaningful to people.

I was just at a rehearsal yesterday and last night, and we had some horse riders that are part of this, ’cause we’re gonna have 20 horses as part of this with riders. And they wanted to participate for various reasons, but the more that you talk with them, the more it actually resonates with how their lived experiences today and why it’s meaningful for them to participate. And again, some of the young women, who, when they get their hand on a machete, transformed just these outdated clothing which they liked into way... really fighting for freedom. This is empowering as they described it. And so, it really transforms the degradation that people are subjected to on a daily basis in this society, into something where people view themselves as part of trying to change the world in really deep ways, I think.

“What if?”—for the Past…and for the Present and Future

MS: Yeah. I think one more thing I wanted to ask you, and, look, you talked about this already a little bit, but this is an art performance about freedom, resistance, and hope, and the importance of acknowledging the power that resides in reimagining your own destiny, as I think you put it. And this actually raises a whole thing that people need to understand: that there is a very important, and very just necessary and strong, importance of this whole story being a “what if?” story. And you started to speak to this, but I think it’s really important that people understand this. This has everything to do... what you’re putting forward here now has everything to do with what people are facing now and what they need to do. So let’s talk about that.

DS: From its conception, this was thought of as a project that had a speculative nature, that really did open up the question “what if?” for the past but “what if?” for the present and future. And you know, part of how I really started to understand that it resonated in people’s bones, was that when I would speak at colleges, particularly historically Black colleges and universities, and a couple of times students would come up to me after the talk and the talk was generally I would have at least one or two historians and one would typically talk about the history of slavery, and another would talk about the history of slave revolts, and specifically the revolt of 1811. And then I would talk about my artwork, and the Slave Rebellion Reenactment project. And students would come up and they would tell me that they didn’t wanna come. They were often assigned to it. They didn’t want to come to something talking about slavery. And then when they heard that there was all these examples, documented examples, of a couple hundred, like 250 examples, of 10 or more people, enslaved people rebelling and having slave revolts in the United States, that was lifting a weight from them. And they wanted to know more. But the more that I talked with them, the more it became clear that they kinda felt... they would look at a situation was like, well, man, why are Black people... why are there 1.1 million Black people in prison? Why are we the ones that are poor? Why are the police shooting us down? Why are we the drug dealers? Why are our families broken, as they like to say? And they really felt a sense of shame actually about being Black, but when they would learn about this slave revolt, suddenly they realized, that wait, our ancestors weren’t slaves, they were people who were enslaved. And that there was this tremendous joy and uplifting sense that they had when they heard about people fighting back and resisting. And that had everything to do with how they saw existing in the world in the present. Now these are kids 18 to 20, or 17 to 22, or something like that. And I don’t know which ones of them participated in, say, demonstrations against police brutality, or demonstrations fighting to stop the climate crisis, or whether some of them had a loftier vision of fundamentally remaking the world through revolution. I don’t know that. But I do know that they actually had this sense that they were not... not only were they not just something wrong with them based on being Black, but really they could be the agents of change in a way that could be bigger than them. That it could really be something about changing the whole world. And that’s really powerful, I think. Or, college students, to suddenly have not only a sense, but some of them got on a mission, including some of them wanting to participate in the reenactment itself, to form the ideas, and then based on those ideas, some of the networks necessary to be part of really radically rethinking and then putting into place those thoughts of how the world could be different. And that’s really inspiring, and shows what the work is about, even though you know I don’t have a... It’s an artwork, it doesn’t have a prescribed ending or way people should change the world or even think about changing the world. But it does actually challenge people in the present to think about that, back in 1811, people identified again: the problem is we’re enslaved; the solution is to end slavery. How do we figure out the difficult and complicated things necessary to do that, and what for us in the present, what are the analogies, what are the difficult things that we realize we’re up against that often people recoil from and come up with things that are not really solutions for the problems they’ve identified, but things that they think are possible to achieve. So starting from a standpoint of identifying a problem and looking for a solution of what’s actually necessary even though you might not understand when you first identify the problem whether that necessary change is possible but you have to go and figure out the work to do that. And that’s what was done in 1811. And that’s the spirit people I hope have now based upon engaging with this artwork, including a lot of the many actors engaging with it and participating in it over the course of months and in some cases years.

MS: And I can’t wait to see what comes of it, man. I’m really looking forward to seeing what happens with this. It’s a brilliant piece of work. It’s a really necessary piece of work and it’s one that can actually have a major impact at a time when a major impact is really needed. So thank you very much, man.

DS: Well, thank you. I can’t wait to see it either. I’ve been working on it a long time. The artwork doesn’t exist until it exists. And so I’m looking forward to marking those 26 miles with hundreds of my closest new friends and I hope that you stay tuned, and look for the news reports and images and videos, and tweet about it. You can go to our website to see more about it. Slave-revolt.com is our website. And on Instagram and on Twitter, we’re just @slaverebellion. But people should look out for it... I think it’s gonna be awesome. And if people can make sure that it’s sunny and dry, I’d really appreciate it, but we’re going rain or shine.

MS: [Laughs] And look, man, I look forward to talking to you when it’s all over, too. I’m gonna talk to you again next week, I think, to try and hear what actually has happened.

DS: And one thing that we didn’t say, it’s important, it’s November 8 and 9.

MS: That’s right.

DS: Fantastic!

MS: OK, we’ve been talking with revolutionary artist Dread Scott. Dread Scott makes revolutionary art to propel history forward. He first received national attention in 1989 when his art became the center of controversy over its transgressive use of the American flag while he was a student at the School of Art Institute of Chicago. And president GHW Bush called his art disgraceful and the entire U.S. Senate denounced this work and outlawed it when they passed legislation to protect the flag. On November 8th and 9th 2019, hundreds of re-enacters will retrace the path of the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history—embodying a story of resistance, freedom and revolutionary action and it’s all brought to you by Dread Scott and his whole gang of cohorts.

Artist Dread Scott interviewed on KPFK's The Michael Slate Show

Aired Friday, November 8, 2019

What I heard most from participants in the #SlaveRebellionReenactment in New Orleans this weekend was the sense of solidarity they felt from each other, their trust and focus on the energy they brought to each other. pic.twitter.com/rWHXNwakcB

— Lois Beckett (@loisbeckett) November 10, 2019

Photo: Soul Brother

Photo: Soul Brother

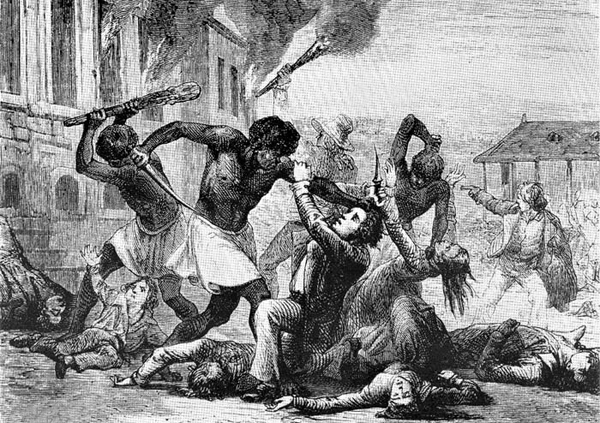

Deslonde Revolt, 1811. Artist unknown

Revolution Club, Chicago—Joining the #SlaveRebellionReenactment in Louisiana!

Photo: AP

Photo: Soul Brother

Keeping spirits high! pic.twitter.com/EGE0cvuWti

— Slave Rebellion Re-enactment (@SlaveRebellion) November 8, 2019

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: