“People were NOT having it ...

a political revolt amongst the students”

Lenny Wolff on the Kent State Anniversary

| revcom.us

Editors’ Note: We are making available to our readers edited excerpts of an interview by Sunsara Taylor with Lenny Wolff on the We Only Want the World radio show, which aired May 12 on WBAI and WPFW. The show also featured Hank Brown, a member of the Revolution Club in Chicago. The audio of the whole show is available here.

***

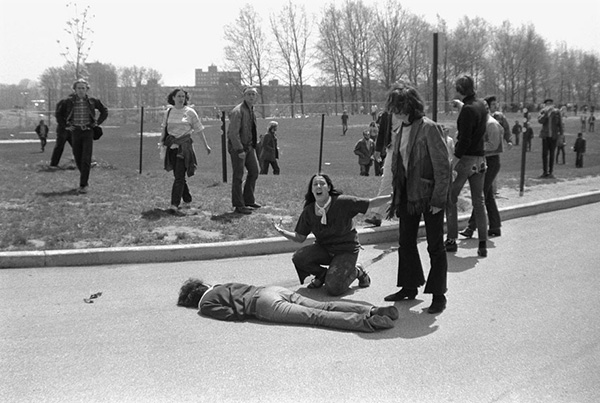

Sunsara Taylor (ST): I’m speaking to you, and you are receiving this information, on the 50-year anniversary of a truly momentous time in U.S. history. And a whole series of events, starting May 4th, just over a week ago, there were four students at Kent State in Ohio who were gunned down, massacred by the National Guard. These were students involved in protest against the Vietnam War, a wave of protests that happened across the country on campuses in response to Nixon bombing Cambodia. So, this was an escalation of the war, this was an escalation of protest and there was massive repression. And four students were shot dead... And after that, coming on Thursday this week will be the 50-year anniversary of a protest at Jackson State University in Mississippi where Mississippi Highway Patrolmen were sent in and opened fire and massacred two more students there and wounded 10 others.

This was a moment of massive repression, but also massive uprising. And I think that it’s very important that there are moments when there are crimes committed against the people by oppressive powers that have the effect of crushing people’s spirits and cowing them and intimidating them into silence. But, in fact, this had the opposite effect. These were times that were very filled with hope and daring among many who were demanding and putting a lot on the line for a different world, for a different way things could be.

First, to set the stage I’m going to play a little bit of audio. I have two clips I’m going to share with you this hour. One is from, the actual audio is rare audio, it was donated to or shared with the YouTube program that I’m a part of, the Revolution Nothing Less Show on youtube.com/therevcoms YouTube channel... shared with us by the filmmaker David Zeiger (Episode 7, available here).

So with that, I want to introduce Lenny Wolff who is a revolutionary and a follower of Bob Avakian. He’s a fighter for real revolution based on the new communism that’s been developed by Bob Avakian. And back in 1970 Lenny was a radical student on campus involved in taking up the defense of Bobby Seale, a leader in the Black Panther Party who was being railroaded—I think we’ll talk a little bit about that, he’ll share a little bit about that. And he was very impacted by and played a role in the protests that followed the murders at Kent State. So Lenny Wolff, I want to welcome you to We Only Want the World...

Yeah, so you were there! I want you to take us back to 1970, what was affecting you in the world and what was going on in your life. Let’s just start right on the ground.

Lenny Wolff (LW): OK, well I think, just to kind of—let’s say, to set the stage, there were two huge things that were going on that young people, in particular, but all generations had to wrap their mind around in the United States in the 1960s but things had also reverberated around the world. And one was the war in Vietnam, and this had... several million Indochinese were slaughtered by the U.S. in that war in what was an effort to crush a struggle for national liberation and independence. And as that war went on, many, many people began to not just see it as unjust, not just to oppose it, but to viscerally oppose it. And this began to include veterans, soldiers in that war. And so this was something that was constantly in the background. And going into Kent State there had been a period where the president at the time, Nixon, had been doing what he called de-escalation, and this was having an effect—which turned out to be a temporary effect—on the student movement that had arisen against the war. And it was somewhat... I don’t want to say dying down, but it had entered sort of a period of intense calm after what had been a big upsurge in late 1969. Almost half a million or three-quarters of a million people protesting at the White House.

At the same time you had the Black liberation struggle that had also become in the minds of millions and millions of people, beginning with Black people and people who had a sense of justice, and then spreading much, much further to all sections of the population who could see there was real right on the side of Black people. And in particular, there was a brutal campaign of repression that had been launched against the Black Panther Party, and this had included a trial coming off the Democratic Convention in which the Chairman of the Black Panther Party had been bound and gagged in the courtroom and then finally removed from the trial—simply for demanding the right to defend himself. And this was on national TV every night and it had a tremendous... at a time when people watched national TV, network news... it had a tremendous impact on people’s thinking.

A few weeks later on December 4th—another 50th anniversary of a few months ago—a leader of the Black Panther Party, Fred Hampton in Chicago, had been murdered in his bed by a squad of police. And this was all building up to a situation where at the very weekend when Nixon was, as you pointed out, invading... he didn’t just bomb Cambodia, they had been bombing Cambodia... he invaded Cambodia with ground troops at a time when he had been promising to de-escalate. That same weekend was right before the opening of the trial in which Bobby Seale was facing the electric chair—again the Chairman of the Black Panther Party at that time.

So these two huge struggles that were definitely moving the soul of America were both bound up in that weekend leading into Kent State.

ST: Well, I think that’s helpful, setting the stage. Could you maybe tell a little bit... you were involved in a struggle at this point. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about yourself at that time and how this was impacting you on, how did it feel, how did it make you think, how did this unfold for you as well.

LW: I had been somebody who had gotten into the struggle at different times, I had gotten discouraged at different times. But I was profoundly alienated from the system, and when Fred Hampton was shot down in his bed, I felt I really can’t just stand aside as a profoundly alienated person anymore—I had to do something, I had to jump into this, I couldn’t let this go down. And I wasn’t alone in that. There were a number of people I know, and people who I don’t know I’m sure, who had similar reactions to that killing, that massacre in the Panther house. And I went back to school to become, you know, as I hoped at the time... I felt if I became a teacher I could do something to at least try to make the conditions better. And at the same time I got myself re-involved, I began to get re-involved in radical politics. And you could say I wasn’t fully both feet in at that point, but I was still more and more gravitating towards that thing, and I had become a very active student on my campus in opposing the war—and as you pointed out earlier, supporting the Black Panther Party. So I was one of the activists at that point.

ST: And then you decided to go... my understanding is you decided to go to the trial of Bobby Seale out in New Haven.

LW: Oh yeah, there was a whole slogan that came out from the Black Panther Party: “Come see about Bobby”—and we took that up and we came and saw about him. And it was very interesting because to go back to what you said at the beginning, you could tell there was a different temper emerging among the people. I went to a meeting, I was part of a meeting that helped plan it, and there were broader students at the meeting than you normally see—like the Theater Department. The Theater Department at my school did not go to meetings, but a couple of Theater Department people came and I heard them talking afterwards and they were weighing the possibility of real danger in New Haven, which is where the demonstration was because that’s where the trial was. It was at Yale University. The National Guard had been stationed at Yale to “prevent outbreaks” and there had been all kinds of rumor-mongering going on of what was going to happen, and this was going to happen, and these students were uh... you know, one student said to the other: “Well, if we go to New Haven, you know we might be shot by the National Guard.” And the other student said: “Well, I guess we better go then.” And they both went, you know. Because people were... it wasn’t that people were looking for a fight or anything like that necessarily, but people were not going to be deterred—there was a section of people who were not going to be deterred by the normal threats that the ruling class uses to bring down on people. And that, as you said earlier, led into the... this was the weekend right before Kent State. It was the weekend... I think it was on the... we were driving all night to get to Yale and we heard on the radio that Nixon had launched a secret invasion of Cambodia and this had come to light. He’d sent U.S. troops across the border, which was a violation also of a congressional resolution, I might add—which also inflamed people because it was an illegitimate, even by the rules of their system, it was an illegitimate invasion. And all this fed into a situation that was increasingly politically combustible, if I can use that word.

ST: My understanding is there were several thousand people who came out to the protest for Bobby in New Haven, is that correct?

LW: At least, yeah. There were quite a few students who came from around the country to be at that protest.

ST: So then just a few days later... so Bobby Seale is on trial facing the electric chair, the leader of the Black Panther Party, you hear on the radio Nixon has invaded Cambodia, and you come back and there’s... there was a... my understanding is there was a big step-up in protest on the campuses, that’s what Kent State...

LW: Well, yeah, Cambodia was invaded!

ST: I want to step forward from there. So Kent State... there was protests against Cambodia, Panthers and the mood of that was in the air. When you heard that the National Guard had come in and shot students... I mean I still find it shocking. I look at the photos... it’s stunning. And a moment ago you were saying people were kind of: “Oh, maybe we’ll get shot if we go out there...” but that wasn’t defining how they were calculating what they would do. And yet, when the students got shot that must have been a shock, it must have been a jolt. Maybe you could talk some about that.

LW: Yeah, I remember... well, one thing is I should say that when we were at the Panther demonstration you had students from all over the country who had heard about this invasion and said we’ve got to launch a massive student strike against this invasion. So that was the intent. And then I remember very precisely where I was when I heard that four students had been killed at Kent State. And I was with a Black friend of mine who was also politically active, and he turned to me and he said: “Man, they’re shooting white students now. This is up off the hook.” And, you know, we had been planning for a meeting that night, and I said: well, we’d better get a room that will hold, I don’t know, maybe a couple of hundred people. Normally, your normal meetings, even at the height of things were 20 or 25 people and then if something really big happened you expected 50 or 80 people maybe, but I thought this is really big. So we got this room and a half hour before people began streaming in. It was really heavy, you know, so we... the room just got totally filled to the brim so we had to get another; we had to go to the college cafeteria. There was several thousand people, students from all these campuses, people from the surrounding communities had come—you know, old people as we thought they were then, they were probably in their 30s, 40s, 50s, were coming. There was just this massive refusal to take this, a refusal to be deterred in the face of this violent repression that had been launched. These students had nothing, they were shot. And after the Guard shot them there were even students at Kent who said: go ahead, shoot me! People were... and then cooler heads prevailed and said: let’s not rush the Guard, let’s not do that now, that’s not what needs to happen. But what did happen and what did need to happen was some of what you described—that people... I think there were over four million students eventually who went on strike, didn’t just go on strike, but went into the streets in all these college towns. The National Guard was sent, I remember, to University of Maryland—all these big universities, they had to send in the National Guard. It was a tremendous massive student... strike doesn’t capture what was really a political revolt of a sort amongst the students at that time. People were NOT having it.

ST: In your sense, why do you think it was that people responded with more outpouring and more outrage as opposed to... I could very easily see students being shot down putting a chill and scaring people back. So why do you think it went the one way and not the other?

LW: I think that... that’s a big question. I think there had been a certain tempering of people over time. This was not... well, it’s true my Black friend said to me that now they’re killing white students. They had killed a white student, not a student but a white community person, a youth in Berkeley the year before at People’s Park. Two years earlier they had killed three Black students peacefully trying to integrate a bowling alley in Orangeburg, South Carolina. People were making sacrifices, and there was a sense that... there was a sense of a moral challenge to the rest of the country from those who had been making sacrifices and a sense that there was a brighter future that could be had and needed to be had that made that worthwhile. You’ll see in the film you just described, when they shoot these students at Jackson State, which was several days after Kent, May...

ST: 14th, I believe.

LW: If you see the film... that Dave Zeiger lent you, if people could see that they could see that there were students who just would not be deterred, who after that really horrific shooting that you have the soundtrack of were out there demanding that the bullet holes not be cleaned up and preventing the maintenance people from cleaning up the bullet holes because, as they say in the footage that goes with the Dave Zeiger clip: people need to see this, people need to see what happened, somebody was killed here. So there was a sense of right on our side; there was a sense of a better future is possible, even if people had all kinds of different understanding of what that would mean and what was involved in that. And there was a moral clearness. You know, we had a slogan at that point we would chant at demonstrations: “One side right, one side wrong. Victory to the Vietcong!” Because you had to make a determination of who was right and who was wrong and you had to, in particular, in an imperialist country, a country, that is, that rules people all over the world, dominates whole nations all over the world—you had to decide which side were you standing on. Were you going to stand with those who were demanding your acquiescence in the oppression of millions and billions of people or were you going to stand against that? And that was... you know, it didn’t come out of nowhere. If you turned the clock back to 1960 and you had said to people in 1960: here’s my prediction that out of what’s happening here in 1960, in 1970 you’re going to have everything you just described about what did happen at Kent State, all that’s going to happen, people are going to be profoundly alienated from the system, all these different things that... even just on the Kent State thing people would have thought that you were crazy because they couldn’t see the source of it beneath the surface. Today you can look back... I think it’s a much longer show than we have time for today, but you could look back and you could see the cracks that were underneath the surface, you could see things, the fissures through which this kind of protest, this kind of rebellion, this kind of hunger for a different world was going to burst through and find expression.

ST: Well, I think that’s really important because, you know, speaking as somebody who wasn’t born till quite a while after this, I learned about the ’60s and, I think even more for younger people, people younger than myself don’t even know what I knew about it, but I learned of it as all the high tide, all the rebellion, and the idea that it came out of the ’50s, that it came out of something that seemed completely locked down, but as you’re describing, there were cracks and fissures... I think there’s a lot we need to... lessons we need to draw from that.

[You said] that if you go back to 1960 there were cracks, there were fissures out of which the full uprisings of the ’60s and 1970s emerged. And I know that is a whole show—it would take a whole show to explore—but I think there’s importance to not seeing things, even if they’re quiet on the surface, as locked down permanently. So, Lenny, I guess the last thing I’d like to ask you is what lessons do you think we should draw from those times?

LW: Let me start with the lesson I drew, which was I think I said earlier in the interview... I had gone back to school, I was thinking I would be a teacher, I was getting more drawn into the radical movement. The experience of Kent State and the huge upheaval in society that resulted, and the deeper reflection I was forced into, actually was very instrumental in putting both my feet on the side of we need a revolution. What was decisive in that, though, was I began to try to figure out how that would be made. I looked into... I began trying to read about the Chinese revolution a little more seriously and I came across a pamphlet that was put out by the Revolutionary Union, the Bay Area Revolutionary Union at the time, called Red Papers, which was being led by Bob Avakian. And that had a very big influence on me in letting me see there was a possibility, that you could see a way you could do this, you could see a method that you could analyze society, and you could see a way through to actually make a revolution. There was... if we had had a vanguard at that time that was rooting itself in a scientific method there’s no telling... you can’t tell... it would be fun to write a counter-factual novel (you know, science fiction, those kinds of counter-factuals) where people actually did try to make a revolution. But you couldn’t have done it... what came clear to me at the time and is even more clear in retrospect, you couldn’t have done it without a vanguard that had a strategy, that had a method of understanding reality, that had a leadership that could do this. We’ve got that now. We’ve got Bob Avakian who’s gone forward from that period and has further developed communism as a science beyond what it had been and as a strategic approach to revolution and to winning in the largest sense, to getting all the way through to not just having a revolution turned back, as has been the bitter experience thus far in society too often. And in fact now there are no revolutionary societies.

But that was what I draw from it... It’s to draw the lessons of that period. If I have one I want to really implore your readers to read a piece that Bob Avakian did: “Bob Avakian Responds to Mark Rudd on the Lessons of the 1960s and the Need for an Actual Revolution.” If you want an understanding of what happened in that period, what lessons to draw, where it went and where it could go, I really, really want to urge you to go to revcom.us. This is right on the landing page: “Bob Avakian Responds to Mark Rudd on the Lessons of the 1960s and the Need for an Actual Revolution.” And that’s what I would say.

Listen to audio:

“No Hope—vs. No Permanent Necessity”

Excerpt from:

Hope For Humanity

On A Scientific Basis

Breaking with Individualism,

Parasitism and American Chauvinism

Bob Avakian

Author of The New Communism

See also:

BOB AVAKIAN RESPONDS TO MARK RUDD ON THE LESSONS OF THE 1960s AND THE NEED FOR AN ACTUAL REVOLUTION

LIBERALS: WHAT IS THEIR PROBLEM?

Reform vs. Revolution—A Reply to a “Liberal” Critique of My Response to Mark Rudd

by Bob Avakian, Author of The New Communism

Q&A: Bob Avakian On The Revolutionary Days Of the 60s, The Heavy Times To Come, The Absolute Need For Science... And the Role For YOU

From Why We Need An Actual Revolution And How We Can Really Make Revolution. Watch the complete speech here.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: