Crucial Lessons from a Previous Hotly Contested Presidential Election

The Hayes-Tilden Compromise of 1877—and the Betrayal of Reconstruction

| revcom.us

Editors’ Note: As we come upon what is likely to be a highly contested election, if it happens, what follows are some lessons from history that are extremely important and worth noting. The stakes at that time included the violent assertion and imposition of a different form of rule. While the circumstances then were different and analogies are limited, we face similar stakes today.

The Presidential election of 1876 came 10 years after the American Civil War ended, putting an end to nearly 250 years of the enslavement of Black people. During that decade, known as Reconstruction, the federal, or Union, army remained in the South as the enforcers of real and significant reforms in the rights of former slaves. Three constitutional amendments passed during the years of Reconstruction, though never fully realized, granted the former slaves the rights of citizens, including the right not to be chained to the land; the right to vote; and the right to hold political office. It is estimated more than 1,500 Black men were elected to high office in many southern states during the Reconstruction era.

But all of these gains were met with the most vicious acts of depraved violence by southern whites, mobilized by the former slave owners in defense of their white supremacist “way of life.” The Ku Klux Klan was founded and grew dramatically in these years, carrying out lynchings, night raids, and terroristic assaults upon newly freed Black people across the entire area of the former Confederacy. Seven months before the 1876 election, the U.S. Supreme Court put their stamp of approval on racial terror in the Cruikshank1 decision, which reversed the convictions of 3 killers in the 1873 mass racial murder in Colfax, Louisiana.

The future of Reconstruction, and the future of the lives of the former slaves, came to a head in the intensely disputed election of 1876. Samuel Tilden of New York, the candidate of the Democratic Party, got more votes than the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio. (At that time, the Democratic and Republican parties were different from what they are today. The Democratic Party was the party of the former slave owners and those who supported slavery. The Republican Party was the party of Lincoln, which had opposed the expansion of slavery.)

A Disputed Election Decided by U.S. Congressmen

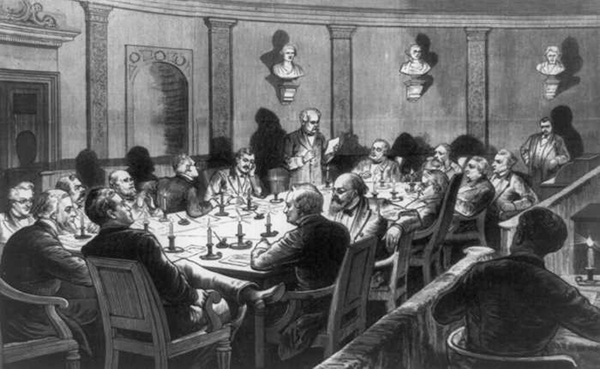

But neither had enough electoral votes to claim victory. The results in three southern states had been disrupted by violence and voter fraud by Democrats. For four months, the person who would become president of the U.S. was in doubt—until an unwritten agreement was struck by a group of U.S. Congressmen to decide the outcome.

In what is known as the Compromise of 1877, a group of politicians decided that Hayes would become President. But in return, Hayes agreed to remove all the federal troops from the South. The terms of this compromise were that the South would have the right to deal with Blacks without northern “interference”—known as “home rule.” There were outcries that Tilden had been cheated, and threats of forming armed militias to march on Washington. But President Grant tightened military security, and the march on Washington never took place.

This election compromise, worked out in a back room by a group of Congressmen, meant nothing less than the reversal and betrayal of Reconstruction. While the full promise of rights to former slaves, including the promise of “40 acres and a mule,”2 was never realized under Reconstruction, there had been significant changes and improvements in the lives of Black people in the South. What would now replace it was a different form of rule.

A 90-Year Nightmare

The result of this electoral “compromise” was that Black people were step by step stripped of even the partial economic and political gains they had made under Reconstruction, and condemned to another century of subjugation and degradation. Southern Democrats regained control of state after state. They passed measures like “black codes,” which restricted the right of Black freedmen to own property or run businesses. The former slaves were again chained to the plantations in conditions of near-slavery as sharecroppers. And poll taxes and literacy tests were imposed—under the threat of violence—to keep Black men from voting. It’s estimated that by 1905 nearly all Black men were effectively disenfranchised by state legislatures in every Southern state.

In this way a whole legal system of white supremacy, called “Jim Crow,” was put into law in each Southern state. And this became enshrined by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. Plessy legalized the formal second-class status of Black people by upholding “separate but equal.” Laws were passed that meant that Black people were legally required to attend separate schools and churches; use public bathrooms and water fountains marked “for colored only;” eat in separate sections of restaurants if not excluded altogether; and sit in the rear of a bus, or in a separate railroad car.

And the Ku Klux Klan became the extralegal terrorist enforcers of this unfolding crime against humanity. The Tuskegee Institute estimates that 4,743 people—mostly Black men and sometimes Black women—were lynched between 1882 and 1968 in the U.S. Their bloated, tortured, disfigured bodies were left hanging in public places—as a warning to Black people everywhere that they could be murdered at any time for challenging their second-class status, or for no reason at all.

Once the rule of white supremacy was put back in place, it became “normalized,” with its grotesque treatment of a whole people, along with never-ending violence. And this continued for nearly 90 years. It was not until the 1950s and 1960s, with the courageous efforts and sacrifice of the people in the civil rights movement, that legal segregation was ended, and the struggle for Black liberation emerged.

1. The essence of the Cruikshank decision was that if a mob of “ordinary citizens” did the killing, and the local and state officials allowed it to happen—that was no violation of the U.S. Constitution. In other words, the federal government would do nothing to prevent the lynchings and pogroms against Black people by organized racist mobs. For more, see the revcom.us American Crime series article The Colfax Massacre of 1873... and the Supreme Court Stamp of Approval for Racist Terror. [back]

2. “Forty acres and a mule" (referenced in Spike Lee films) was the promise of land (and the basic means to work it) that was made to Black people during the Civil War. [back]

Cruikshank decision in 1876, reversed conviction of three killers in the 1873 Colfax Massacre depicted here.

Cruikshank decision in 1876, reversed conviction of three killers in the 1873 Colfax Massacre depicted here.

Electoral Commission of 1877 decided that Hayes would become president in return for removal of federal troops from the South, and thus allowing the South to deal with Blacks without interference. It was a whole different form of rule. (Image: LOC)

Electoral Commission of 1877 decided that Hayes would become president in return for removal of federal troops from the South, and thus allowing the South to deal with Blacks without interference. It was a whole different form of rule. (Image: LOC)

Ku Klux Klan carried out night raids and terroristic assaults upon freed Black people throughout the South. Image from Texas History textbook.

Ku Klux Klan carried out night raids and terroristic assaults upon freed Black people throughout the South. Image from Texas History textbook.

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: