Hank Aaron: More Than a Ballplayer—A Voice Against the Oppression of Black People

Thoughts from a reader on the death of Hank Aaron

| revcom.us

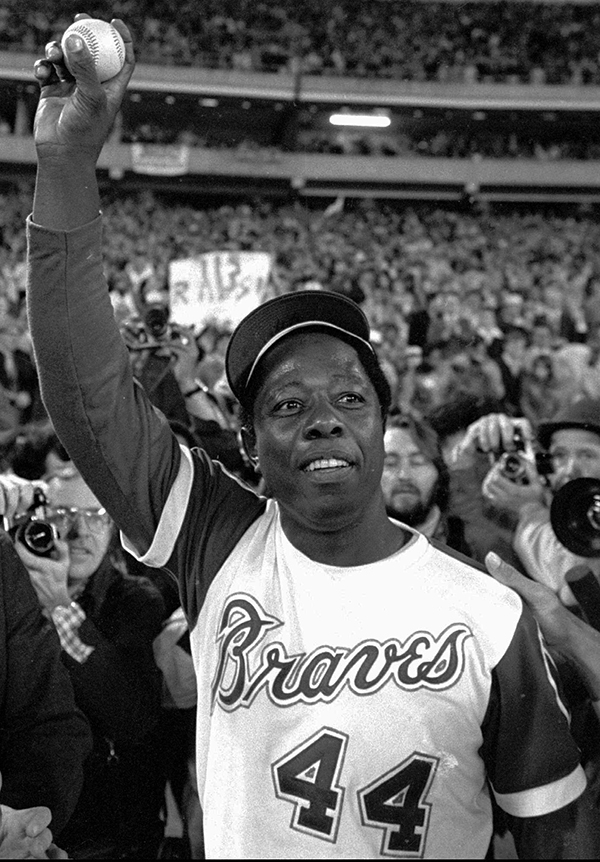

On January 22, we lost a great baseball player, but more than that, we lost a great human being, who used his platform as a voice for the struggle of Black people against their oppression.

Known as “Hammerin’ Hank” on the baseball diamond, Aaron ended his career in 1976 with a total 755 home runs, the most of any player at that time. He was known as a home run hitter, but his lifetime batting statistics, in all categories, put him right at the top with the best hitters of all time.

Aaron often spoke about the conditions of Black people—injustice, oppression, and segregation. He said, “On the field, Blacks have been able to be super giants. But, once our playing days are over, this is the end of it and we go back to the back of the bus again.”

As Aaron approached breaking Babe Ruth’s career home run record of 714, he became a focus of white supremacist racial hate in this country. Millions of white people did not want a Black man to break the most important baseball record held by a white man. Aaron shared one letter he got with Sports Illustrated: “You are not going to break this record established by the great Babe Ruth if I can help it. Whites are far more superior than jungle bunnies.… My gun is watching your every black move.” People sent him letters telling him they would kill him just like Martin Luther King Jr. was killed.

In discussing that period of time Aaron said, “It brings back a very foul taste in my mouth. I had to send my kids to private school. My daughter, who was in college at the time, couldn’t go out of the dorms. She was threatened with letters all the time. It was a horrible moment for me to try to break the record, really. The police were saying all of these probably are crank letters, but some of them maybe were for real. The team stayed at one hotel and I stayed at another. I sometimes had to sleep in the ballpark by myself. I had to slip out of back doors of ballparks.”

Dusty Baker, who played with Aaron from 1968 to 1975, talked about how Aaron dealt with things during that time. Baker said, “He’s a strong man. A strong Black man. This made him stronger and more determined and he concentrated harder. It wasn’t only playing against Babe Ruth, he was playing against parts of America.’’

Aaron played for the Milwaukee Braves from 1954 to 1965. In 1966 the Braves moved to Atlanta. Aaron was born and grew up in Mobile, Alabama, where the KKK terrorized and murdered Black people. He had trepidations about going to play in Atlanta. “I have lived in the South, and I don’t want to live there again,” Aaron said at the time. “We can go anywhere in Milwaukee. I don’t know what would happen in Atlanta.” Atlanta was not friendly for him in the beginning, as he received racial taunts from people in the stands. Eventually Aaron found his place in the Atlanta, where he lived in the Black community and became close friends with national civil rights leaders in the city.

On opening day in Cincinnati in 1974, Aaron was one home run away from tying Babe Ruth’s record. When the people there asked him what they could do to honor him, Aaron requested they hold a moment of silence to remember the death of MLK. A few minutes later, Aaron broke that silence by hitting his 714th homer. Four days later, in Atlanta, he hit number 715, breaking Ruth’s record.

I personally saw Aaron play several games against the San Francisco Giants. I remember one game in the early 1960s seeing Aaron hit two homers. It was always a very special treat to go to a game to watch two of the greatest players of all time, Willie Mays of the Giants and Hank Aaron of the Braves, play on the same field.

After baseball, Aaron became a philanthropist, donating millions of dollars to different Black causes. The Atlanta Journal Constitution reported, “In 2016 Aaron and his wife Billye Suber Aaron donated $3 million to the Morehouse School of Medicine as part of an expansion of academic facilities at the Atlanta institution.” His long-time Atlanta friend, Xernona Clayton, said, “He let people know ‘I’m there with you.’ He understood the pain of segregation and discrimination. He never forgot who he was and what the needs were of Black people trying to get equality and justice.”

Hank Aaron (AP photo)

Hank Aaron (AP photo)

Get a free email subscription to revcom.us: