Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/048/border-crisis-revolution.html

Revolution #48, May 28, 2006

The “Border Crisis” And Revolution: Stepping Back on Some Strategic Dimensions

This week George W. Bush gave a major speech on immigration. Two things must be said about this speech, right from the start:

One: While Bush may pose as a “moderate” on this issue, a study of his speech—and more than that, a real look at the bill he is pushing—shows a raft of very ominous and new repressive measures. Taken together these will amount to a radical change for the worse in the lives of millions, even tens of millions, of people.

Two: The struggle for immigrants’ rights must continue and intensify, reaching out more broadly and refusing to compromise on the fundamental rights of the immigrants. Especially in the face of the reactionary storm being whipped up against it in both the Congress and the airwaves, it is very important for this movement to renew its offensive and get the truth out there.

And with those two points, a third: there is a larger dimension at work in Bush’s proposal to further militarize an already-militarized border, this time with National Guard troops and a leap in electronic surveillance, and to force undocumented workers to carry government-issued, biometric ID cards. And that has to do with the real fear this government has of political upheaval, even revolutionary upheaval, that could “cross the border.”

How Did We Get Here?

Mexico today is an extremely oppressed and extremely complex nation going through breakneck changes. The 1994 NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Act) enabled U.S. capital to even more deeply penetrate, and twist, the Mexican economy, and it accelerated the upheaval in Mexican society. NAFTA drove even more peasants from the land and into the shantytowns of the cities. There has been industrialization and de-industrialization, and the old “social compact”—in which the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) basically ran the country’s political institutions—has been racked by turmoil and change.

Now it’s important to understand and never forget, especially when there’s so much talk about “defending ‘our’ borders” (both from open reactionaries and even some people who should know better), that this domination by the U.S. stretches all the way back to the U.S. military invasion of Mexico in 1846, and its robbery of half of Mexico’s territory. And note as well that the U.S. felt no hesitation about sending troops again to cross the border, this time in 1916, in an attempt to crush the Mexican Revolution.

This whole history and structure of exploitation and domination, combined with the intensified ravaging of Mexico today—along with U.S. capital’s drive to maximize exploitation of workers within the U.S.—has driven the big increase in undocumented workers from Mexico in the past decade. The money these workers send home plays a very important economic and social role in Mexico now—right now, it is the second largest source of foreign revenue in Mexico, right after oil. And the ways in which these workers are outlawed and suppressed within the U.S. makes them essential to the U.S. economy. They are “skinned twice” by the U.S. capitalists—and then skinned yet a third time when they are blamed for society’s many ills.

The U.S. ruling class needs to maintain this section of the proletariat in extremely exploited conditions, and they also fear even greater instability in Mexico if this situation were upset. At the same time, as they themselves say, “the system is broke”—the way that things are set up now is unleashing too many forces that the imperialists feel can threaten them, and so they are moving to make very radical and severely repressive changes in the whole setup.

The “Shadows” . . . and The Fascist “Solution”

Bush in his speech talked about how “illegal immigrants live in the shadows of our society. Many used forged documents to get jobs. . . They are part of American life, but they are beyond the reach and protection of American law.”

Over the past 25 years the state in the U.S. has qualitatively heightened its control over people; with Bush, this has taken a further leap, with the wiretap scandals being just the latest outrage. This is designed to both deal with dissent and protest that does not rise to the level of revolution, but it is also being done with the possibility of bigger things in mind. Among other things, these people remember the ‘60s. . . and if you think that they do not see the potential for upheaval, including revolutionary upheaval, that not only reaches but goes far beyond that era . . . and if you think that they are not readying this whole apparatus to do a very rapid and very thorough repressive clampdown should a situation arise in which they think they need it . . . then you may lack both imagination and realism.

Now the fact that 10 to 20 million people must live outside the law, lacking in any basic rights and liable to be arrested and deported at any moment, gives the capitalists huge power over the undocumented workers. This is why they are forced to “live in the shadows,” as Bush put it. But there is also a way in which this comes into conflict with the imperialists’ strategic aim for a qualitatively greater level of repression in society as a whole.

What does it mean, in light of that aim, for there to exist, right within the borders of the U.S., a population of 10 to 20 million people who have mastered the capabilities involved in “living outside the law” as a fact of daily life? How does that affect what the imperialists perceive to be their strategic need to straitjacket the population as a whole? And yet they can’t just kick everyone out overnight—even Tom Tancredo, as much as he may agitate for it, knows that such a move could cause massive social and political upheaval and possibly rebellion, both within the U.S. and Mexico too.

So the imperialists wonder: would it be better for them, at this point, to “regulate” the immigrants in a different way—finding a way to bring them “out of the shadows” legally, while still keeping them in a highly vulnerable and exploited position as “guest workers”? (See box “The Brutal Reality of ‘Guest Worker’ Programs” in this issue.)

Think about Bush’s call for “a new identification card for every legal foreign worker,” using “biometric technology, such as digital fingerprints, to make it tamperproof.” First off, no one should be forced to put up with that level of invasive control from this state. The people who run this society have proven over and over again that they will use anything open to them to spy on people and worse, and they will definitely use this to hound and more tightly control immigrants. When you add in the fact that many immigrants come to the U.S. with some important direct experience with and political understanding of what this empire does all over the world, and when you further add in the ways in which the recent upsurge has shown their potential to influence the political terrain very broadly, you can see even more clearly why these new, highly repressive measures are being pushed.

Not only that, there is no doubt that everyone with brown skin will suddenly be asked to prove their legality, and that only this new “biometric” card will do for them. On top of that, these fascists have unleashed a hysteria where there are now laws being passed where, for instance, anyone who rents to “an illegal” can be fined. So we will soon have a situation in which anyone who “looks like a Mexican” or “looks like a foreigner” will find themselves in a new version of South Africa: forced to “show their papers” whenever they want to do anything. And so yet another section of people becomes “presumed guilty.”

And think about this, too: how will such an ID card for “guest workers” even be useable unless all workers, documented or not, have such a card—for otherwise, couldn’t people just forge documents claiming that they were citizens? And once you need such a card for a job, how long before—in the name of “security” or even “convenience”—such cards become mandatory for everyone? How long before we’re living the movies Gattaca, Minority Report, or Enemy of the State? (http://rwor.org/a/v23/1130-39/1132/ids_gattaca.htm) If people resist these moves, they could boomerang.

And note also that Bush is calling for a huge expansion of “detention facilities” for undocumented workers—so-called “facilities” in which the conditions are often even worse than in the prisons of this country. These detention centers will be used for people who have already been categorized as criminals without trials, “aliens” not deserving of the most basic rights. And this will be brought to you courtesy of the same people who gave you Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo—not to mention the ugly, illegal repression that has been going on against Arab immigrants since 9/11.

Finally, Bush is calling for MORE repression on the border—National Guard, more INS agents, etc. So let’s remember here too that this will translate into more deaths of people attempting to cross the border in even more remote and dangerous places. Since 1994 over 400 people a year have died trying to cross; that is an outrage and a crime, which will now grow worse if Bush and his “coalition of Democrats and ‘pro-business’ Republicans” get their “moderate” bill passed.

These proposals of Bush are not “moderate” at all; they are vicious attacks on immigrants and very ominous steps in the further fascization of U.S. society. At the same time, they are full of potential risk for Bush and the class he represents. Already this move has created even greater anger against the U.S. in Mexico, as well as other countries. The Sensenbrenner bill politically awakened the masses of immigrants in an unprecedented way, and where this all will end up is far from settled. There are problems that this is causing in the border regions of the Southwest, where the peoples and economies on both sides are very intertwined; these new measures will tear all that apart. And there is the question of what all these changes will do to the families of people who are here, where half the family is “legal” and half is not.

On the other hand, there are all these “America über alles” types who have been unleashed who don’t want to settle for anything short of what would amount to ethnic cleansing; their ruling class masters can’t, and don’t necessarily want to, just put these people back into the bottle. So you have people like Tancredo or Sensenbrenner threatening to “break ranks” with Bush; part of that is a show designed to placate these people and “give Bush room” to make the “final compromise” even more extremely repressive, but part of it reflects the real difficulties in pulling this off and real conflicts over how to do it. In short, there are many different ways in which this could backfire right in the faces of the imperialists. And that is why they are having problems actually pulling themselves together on this.

Polarization . . .

It’s important to get this point... The needs of the U.S. imperialists for immigrant labor on the one hand, and the ways in which the presence of millions of immigrants undermines the uniformity and “cohesiveness” of American culture, politics and thinking, forms a sharp contradiction for the U.S. rulers; and their very efforts to deal with this, as we showed above, can give rise to further centrifugal forces.

It’s not for nothing that Bush demanded in his speech that people speak English and “respect the flag” as a symbol of “shared ideals,” and that the Senate followed up by passing a law declaring English the “national language”; and it’s not for nothing that both the open enemies, as well as some of the friends (both well-meaning and false) of the immigrants make an issue out of people flying flags other than the U.S. imperialist rag. The U.S. rulers have real concern over holding this country together, on a reactionary basis, and they are using this crisis to push a very ugly xenophobia (that is, hatred of foreigners).

They are using immigrants as scapegoats for all the insecurities and problems and fears of the future that their system has forced on the majority of people in this country. And at the same time, they are trying to make the immigrants feel alone and isolated. “Blame them for your lives,” the rulers tell the native-born, pointing to the immigrants. “They’ll never help you,” these same rulers say to the immigrants, pointing to the native-born. This is a very ugly game, one that has historically led to death camps, and it has to be understood for what it is and opposed.

...And Repolarization for Revolution

Left to itself, this polarization will not end up anywhere good. We need to RE-polarize what now exists, and repolarize it for revolution. But this repolarization is not a one-size-fits-all thing; it has a lot of dimensions to it.

There is the continued need to help set the right demands and dividing lines in the movement for immigrants’ rights, struggling against those lines and programs which would lead the masses’ demands for freedom into a dead end—showing people with substantial arguments where the different positions will lead. There is the need to go among those people, both in the middle classes and in the working class, among all nationalities, who are holding back from or even opposing this movement, and speak to their questions and what is hanging them up and even driving them into backward stands, and win them over through debate and struggle. And while we are doing all that, we have to be bringing the full communist solution, and the real potential for revolution, out very broadly—in society overall and also within this movement itself.

Which gets us, finally, to our last point. The current crisis shows the potential for something way heavier to emerge. A few years back Caspar Weinberger—the Secretary of Defense under Reagan, a man who stood out even among imperialists for his vicious cold-bloodedness—wrote a novel set in 2003 that included a future U.S. military invasion of Mexico. Part of what precipitates the U.S. invasion in the novel is a massive influx of Mexican immigrants over the border. This gives a little bit of a window into the kinds of calculations being made by the imperialists, as well as what they want to begin getting the public to think about and accept.

Could that happen? Are they really considering this? Well, ask yourself this: what would it mean in today’s situation if a truly revolutionary movement, one that challenged the foundations of the existing imperialist relations with the U.S., were to emerge in Mexico? Or, what would it mean if even a figure like Hugo Chavez—i.e., someone who is not revolutionary and not trying to rupture with imperialism overall, but who would nonetheless seek to change some of the ways in which Mexico fits into the imperialist system in a way that conflicted with U.S. plans and objectives—what if someone like that took the reins, and there was big political ferment in Mexico? What would it mean, in this situation, for the U.S. to do what it has attempted to do with its coups, both successful and not, in places like Venezuela and Haiti? In fact, that is exactly the scenario envisioned in Weinberger’s book that leads to a U.S. invasion.

But again, there are many different things that can happen. Better forces, targeting imperialism itself and going for real liberation, could be in the mix of something or even in the lead. The point is that when you have the kind of social instability and crisis we have today as a backdrop, with the ruling class here moving to radically affect the ways that tens of millions of people both north and south of the border have survived, it becomes a political tinderbox. In that context, seemingly random events could become political flashpoints, and something that started out as one thing could develop into an uprising aimed against imperialist domination in Mexico.

For some years now, Bob Avakian has pointed to the potential links between revolutionary struggle in Mexico (and Central America) and the United States, and has argued that revolutionaries should be working toward genuinely revolutionary struggles in both places mutually influencing each other, with revolutionary struggles on both sides of the border giving political support to one another. [See, for example, “Bob Avakian: Two Talks on Preparations and Possibilities,” Revolution, Summer/Fall 1988; see also A Horrible End, or An End To the Horror?, 1984, pp. 64-65.]

In that light, it is quite possible to envision a scenario in which, on a qualitatively greater level than today, the development of the social situation and of revolutionary struggle in Mexico would interpenetrate with and have repercussions on the development of social contradictions and social struggles in the U.S. This could have a tremendous impact, this can influence native—born people in positive ways towards a more internationalist view. It would hold the potential for further igniting and positively interacting with rebellion, and with more conscious and organized revolutionary struggle, in the U.S. itself. And certainly, the imperialists, with their greatly heightened repression, are reacting in part to this possibility, as well as the more immediate concerns we’ve outlined.

Class-conscious proletarians and people of any strata who want justice would welcome an upsurge from south of the border, and would build massive political resistance against any attempts to suppress it or to intervene on any basis. And they would welcome, and lead others to welcome, the influence of that upheaval and turmoil finding political expression within the U.S. Within that, immigrants could very likely play a pivotal role, one that could express itself in many different forms—which is yet another reason why the U.S. ruling class now is intent on isolating and demonizing immigrants.

All that—again, including Caspar Weinberger’s novelistic scenario—has to be kept in mind when you think about Bush’s proposal to station the National Guard on the border. Clearly, there is a real element of attempting to “gain control” of the border here. But there is this larger dimension at work as well.

The whole contradiction around immigrants, along with other intense contradictions these imperialists face, could, as things develop, become part of a larger opening in society which could pose a possibility of making a revolution. But wrenching a revolutionary opening out of this whole calculus, even as it applies to the particular “faultline” of struggle around immigrants, would hardly be easy and certainly not automatic. The rulers are whipping up a fascist movement against immigrants, they are using this crisis to force further repressive measures into place, and they are in fact further militarizing the border—and they are doing all this on two tracks, so to speak, both dealing with the crisis of today as well as preparing for a bigger crisis tomorrow.

We have to confront this fully—both the weaknesses that are driving them to take these radical measures and the ways in which this can exacerbate some of their problems; as well as the ways in which they aim to and could strengthen their hand by doing this, if they succeed. Only through more deeply understanding this in all its motion and complexity—and on that basis mobilizing people to resist this, in different ways and dimensions—can we work in such a way so as to hasten the possibility of a possible opening for revolution...and develop the capability to seize on it should it occur.

That means hard work and hard struggle and risks. But when you think about what is bound up in just this one outrage of imperialism—the way that people are driven from their homes to be exploited and oppressed in foreign lands, and then hounded and humiliated and persecuted, the way that lives are torn apart and even destroyed—when you think of that...

And when you think of how the world really doesn’t have to be this way, and what kind of world people could bring into being, rising above the dog-eat-dog with a whole new way of living, cherishing diversity and building unity, when you think of what possibly could be won...

And when you think about the possibilities for revolution that are pregnant within these very contradictions, if we relate to this with a truly communist stand and method...

When you think of all that, then...isn’t it worth it to give everything you have to make it happen?

Permalink: http://revcom.us/a/048/darwins-nightmare-review.html

Revolution #48, May 28, 2006

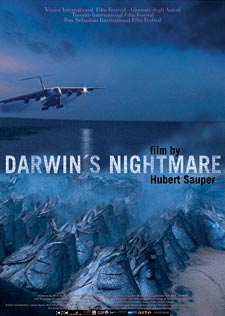

Film Review: Darwin’s Nightmare

The following review of the movie “Darwin's Nightmare” is from A World to Win News Service (December 19, 2005):

19 December 2005. A World to Win News Service. The once spell-binding natural beauty of the landscape around the shores of Lake Victoria in Tanzania stands today in sharp contrast to the wretchedness of the inhabitants and their fly-infested, horrendous surroundings. This is part of the Great Lakes Region of Africa, said to be the origins of humanity. Today, the people live mainly on fishing and the fish processing industry all along the shores of these lakes. The documentary film Darwin’s Nightmare reveals virtually all the contradictions in and around Mwanza in scenes taking place in a fish factory, the factory manager’s office, an isolated airport, tiny leaf-thatched hovels called homes by the village folks. An international conference on ecology, a conference room for bureaucrats and visiting European Union Commission dignitaries, the compound of the National Institute of Fishery, massive former-Soviet built Ilyushin cargo planes from Russia, hotel rooms for airline pilots and plane crew members from Europe. The film brings out graphically all the horrors of utter destitution—the continuing impoverishment (half of Tanzania’s population live on less than a dollar a day) and exploitation of the country and its people under the domination of the great powers of the day—making the viewer seethe with anger.

This film brings home the many contradictions in Tanzanian society which are clearly tied into a knot… and over and over again our hearts scream out for the great need of the people to rise, rise in revolution...

We see so many children in rags, anywhere from four or five years old to ten and twelve. The playful, the silent, the timid and shy, the insolent and brazen, the aggressive and the pitifully bullied. Kids waiting impatiently, with plates and bowls in hands for rice and fried fish-head handouts, while older boys do collective cooking in the warm night air. When the cooking is done, kids scramble over every morsel of food. We see kids sniffing glue so they can fall asleep and forget that they have nowhere to live. So many children and youth with only one leg scurrying along on crutches. Children giggling, playfully wrestling, quarreling, bullying and fighting like children anywhere in the world. Very young girls sticking close to even younger boys for relative safety lest older boys attack or abuse them sexually.

We see too the spread of the tentacles of the hideous “free-market” in this desolate but rich region: cartloads of the giant Lake Victoria fish destined for the supermarkets of Europe and Japan, now heaved and shoved towards the factory. Boatmen busy repairing fishing nets and boats—all for bare survival. Youth and adults in tatters, wading, ankle-deep in muck and piles of remains of rotting fish, laid out to dry in the sun. Kids and elders alike foraging, fighting over tidbits. Maggots and worms crawling over rows and rows of fish skeletons and heads, all that’s left for sale to the common people after the succulent meat has been neatly carved out and processed for export. Frenzy of activity: factory workers hard at work. Boatmen hacking and sawing, fishermen hauling in their catch.

As deeply troubling and even revolting for anyone concerned with questions ranging from ecological disaster to the ruining of human lives as it may be, Hubert Sauper’s award-winning film (Best Documentary European Film Award, the winner of the Grand Prix du Jury Award and the Europa Label Jury Award) is a must-see. It seems as if a great disaster has struck the land and its people, but there has been no tsunami, no hurricane, no earthquake, neither flood nor mudslide here. We see pictures of people, brought really close up, real live characters going through unbelievable daily injustices and torment. The ruthless exploitation of the working people, deaths of the hapless in villages, women forced into prostitution and scourged by AIDS, lungs assailed by poisonous gas, all consequences of international relations glamorized so often by the great powers of the earth, which come by the name of “free trade,” the “free market economy”—and in these days, “globalization.” What these words really mean for the people comes out stark and real.

In the 1960s a new species of fish, the Nile perch, was introduced into Lake Victoria as a “little scientific experiment.” Prior to this, Lake Victoria, the largest lake anywhere in the tropics, was teeming with about 400 varieties of fish. Many of the other species eat up the decaying algae, an overgrowth of which could consume the oxygen in the lake and hence their spread could suffocate the fishes. Thus the wide variety of fish constantly ensured adequate supply of oxygen in the lake. But this new breed is a voracious predator that even cannibalizes its own young. It can grow up to almost double the size of an adult human, weighing as much as 200 kilograms, about 440 pounds (40 kilo fish, about 88 pounds, are common in the daily catch). It has devoured 95 percent of the native species in a single decade and is reproducing itself very quickly. The rapid fall of the oxygen level, owing to the disappearance of other, smaller fishes that feed on algae, endangers all life in the water of the lake. In the end the Nile perch too will become extinct. This ecological state of affairs is bringing 14,000 years of evolution in this lake to a tragic end.

The villain of the film is ostensibly the Nile perch. But an even greater predator, with a more voracious and never-ending appetite for profits and power, a far bigger player on a global scale—the imperialist political, economic and social system and its international relations—soon comes into sharp relief.

Fat juicy fillets for Europe and Japan, lean pickings for locals

Sauper’s camera takes us into the factory, a hive of activity. Here the workers toil away, expertly carving out the fillet of the denizens from the deep and tossing their heads and skeletons onto large waste bins, cleaning away the scales and fins, sharpening their knives, loading and unloading crates and bins of fish and waste. The fillet themselves are loaded onto conveyor belts that carry them into machines for further processing and then to the packing area. A quality control worker tells the camera that most people in the country cannot afford to eat the fillet. These are strictly for export. When asked if he is aware that a famine is looming over Tanzania, he looks bewildered… and falls silent.

Just as painful to watch are scenes of Mr. Diamond, whose factory employs 1,000 workers, and the men around him, the smug and gloating local exploiters (his business partner and his management staff). “We are the pioneers here,” Diamond proudly boasts. “The fishing industry has provided jobs for all the people, all around the shores of the lake, all the people in the region, in Mwanza and Musoma, and even as far as the central region, have work and are totally dependent on the fishing industry.” Diamond gives the impression that there is general prosperity and well-being in the region owing to the export of Nile perch fillets. Each day, two planes land and take off laden with fish and “the airport is busy,” he says. Diamond further reveals that many entrepreneurs have successfully applied for loans and financial support from the World Bank and are today doing very well in the fish industry.

Sauper immediately takes us into a slum area on the outskirts of Mwanza. Amid the squalor of the surroundings, “Life Tastes Good,” declares a large Coca-Cola billboard, one of many that adorn the landscape. And giant-size concrete models of Coca-Cola bottles, complete with its notorious label, stand here and there amidst rows and rows of houses—frames of sticks and tree branches upon which hang plastic and canvas sheets. Trucks unload the waste on a vacant ground, surrounded by the shantytown. The people here, mainly village women around the dump, have erected very many large racks and frames of wood and sticks, upon which they hang or place the salted fish skeletons with heads intact, to dry under the sun. Young boys chase away the white cranes and crows hovering overhead, descending, trying to pick at the fish, along with a myriad of flies and other insects. While the workforce in the factory Saupert visited employed overwhelmingly male and young, here on the dump women struggle for their families. The stench of the rotting fish almost assails our nostrils.

A one-eyed woman working among the garbage complains that the poison in the air causes blindness and respiratory problems for the folks around here. There is a dangerous level of ammonia in the atmosphere says the caption. A middle-aged worker hanging up fish remains says that life is looking better for her. In the “backcountry” where she used to be a peasant, she says, there is no work, no way to earn a living, no money, no food and clothing. It is better to earn some cash here than to stay in her village, she declares. Here, at least, she says, she can earn her livelihood among the filth and odor… She looks around and almost whispers that she cannot talk any more. Her boss is cautioning her to say no more and get on with her work.

Sauper does not make any conceptual remarks here, but the footage makes it plain as bright daylight. The global market—world capitalism—is the greatest predator the world has ever seen and its much vaunted “magic” is able to turn human beings into scavengers scrambling for whatever they can to survive.

Unexpected talents appear too. Local self-taught artist and chronicler, young Jonathan shows his multi-colored crayon drawn pictures of life around him. His picture collection includes the giant Ilyushins landing at Mwanza airport, children smoking drugs in dark alleys; he too was like that he confides. It was to forget the pangs of hunger and hardship. He has also drawn pictures of children sniffing glue, older boys fighting with broken bottles, a body sprawled on the ground, bleeding, a young woman begging for money from a driver of a stationary car, “for her living so that she could survive.” “Perhaps she is a prostitute,” he surmises. Jonathan relates stories of orphans, fishermen’s children abandoned by drunken parents, parents suffering from AIDS.

Jonathan also tells of a time when an airplane was raided by the authorities and a large cache of modern firearms was discovered on board. Those weapons were destined for other African countries, Jonathan says. When asked how he came to know of this, he replies, “It was in the papers, on radio, on TV.”

“We sell our country”

Once again in Mwanza town. The scene: a conference hall. A delegation of European Union Commissioners sit on one side of a conference table. An exuberant delegate congratulates the political representatives of Tanzania’s capitalism, seated on the other side, for the high quality of the fish produced and the “world-standard” sanitary and hygienic conditions under which they are processed and packaged for the markets of Europe. Fish from the lake region account for 25 percent of Tanzania’s export earnings, we are told. They provide the perfect illustration for the Marxist term comprador capitalist, meaning capitalists in an oppressed country whose business is dependent on the international imperialist economy and who therefore are politically subservient as well.

We also see an international conference on ecology, with top bureaucrats and leading business and political figures from abroad and Tanzania, including a government minister and his delegation. The audience is shown a documentary film. A film within the film. It is about the Nile perch wiping out other species of fish in Lake Victoria and choking all life in the water.

The honorable minister is not at all pleased with the theme of the film. “We are all here for one purpose only,” he announces loudly. That is, “How we can sell our country, sell our lake, and our fish.” “Film-making is a process,” he declares, in which a filmmaker takes the parts he feels important for his story and discards others he deems irrelevant. “But here, the producer jumps suddenly from one part to another… Of course, not all of the lake is polluted, dirty and green with algae and lacking in oxygen.” The lake and its fish bring in vital income to the country, contends this fat minister. “We have to look at the positive side of the fishing industry. We cannot be all negative.” We have to market our country. We look to the positive side and “sell our country.” The chairperson of the meeting, apparently an important state functionary, does not demur. “We should not be one-sided, all negative. We weigh the positive against the negative and sell the country.” Indeed those in authority are shamelessly chorusing before Sauper’s camera that Tanzania’s human and natural assets must be sold to the highest bidder.

Victoria Blues

Back in Diamond’s office. “These are tough times,” Diamond says. Business has slumped these days. Oversupply and a glut in the European market. Not long ago, he asserts, he used to ship 500 tons of Nile perch per day. How many people can be fed with the 500 tons? He has no idea… Two million people, the caption on the screen immediately states.

An East African newspaper lies on Diamond’s table. Its headline warns of famine. Diamond expresses his doubt on the accuracy of the news, yet he acknowledges that there is a drought and rice cultivation requires a great deal of rain. There will be severe shortage of rice in the country and prices would soar the following year, he admits. When asked what is going to happen as a result, he shrugs and says that the state would import food and other stuff from abroad.

While drought and other natural disasters trigger food crises, the previously food self-sufficient subsistence farming sector is destroyed through the import of cheap grains and manufactured foodstuff from abroad (mainly from imperialist countries). This is what has caused so many peasant communities to abandon food cultivation. Such economics is strenuously forced on third world countries by the IMF and the World Bank in the name of free trade, economic liberalization and structural reforms. These have given rise to wholesale ruin and uprooting of rural communities, resulting in chronic food shortage in the countryside. This is the underlying reason for the increasing poverty and food shortage in many African countries. To compound this problem, food subsidies are discontinued at the IMF’s insistence, while prices of imported food items rise—making them unaffordable for the poor.

Like many Sub-Saharan African nations, Tanzania used to grow enough food for its people. Now its economy is held for ransom by the global market economy, inexorably pushed by the imperialist system, by its workings, by its ever-widening worldwide structures, ever-tightening nooses around people’s necks, as well as by the state. It has become dependent on food imports as local farming communities abandon their fields and villages in search of quick cash, that is, working to export fish, and toiling on plantations to produce export crops for the world market. When the remaining food crops fail, as is happening now in Niger and Malawi, people die. In producing riches for imperialist capital, the people have become prisoners of a system whose other product is starvation.

Each day, giant aging Soviet-era cargo planes land at the Mwanza airport to take Nile perch fillet to Europe. The airport is also where the Russian air crews—pilot, co-pilot, navigator and engineer—do their own improvised maintenance work on the plane, rest and recuperate—and also spend their time and money enslaving local women.

Christmas presents: guns for Africa’s children, grapes for European children

A Russian pilot admits that he had previously unloaded military equipment in Afghanistan. When asked about arms delivery to African countries, he is evasive; he at first denies it. When the question is put to him somewhat differently, he changes the subject. “This is my co-pilot,” he jokes, smiling at a photo of a cute little kitten in his hand. He finally admits that he once delivered modern weapons to Africa—tanks to (civil) war-torn Angola. After delivering arms to Angola, he flew to South Africa, loaded the plane with grapes and returned to Europe, he reveals a little further. “The children in Africa receive guns for Christmas and the children in Europe receive grapes. Here is a little story from me to you.” After reflecting on this for a while he solemnly declares that he wants all the children of the world to be happy.

On a hilltop overlooking the town, with dark clouds gathering above, Richard Mgamba, a local investigative journalist, reveals that the Ilyushins don’t come into Mwanza empty. They bring in modern arms and military equipment meant for the Democratic Republic of Congo (where 4 million people have lost their lives in the last five years of civil wars) and other conflicts in Liberia, the Sudan, and elsewhere. Mwanza airport is a conduit for these arms deliveries from Europe, Mgamba discloses, bringing additional profits for the transport companies that own the planes. All the European nations have security apparatuses and intelligence services—why can’t they stop the arms trafficking? he angrily demands. Many viewers will conclude that they don’t want to—because the imperialists ship arms to stir up and fuel local conflicts in order to serve their own contending interests.

Condoms and sin, Hallelujah! and all that

In one of the most heart-rending scenes, the film takes us to see AIDS-stricken women, one of whom can’t even stand up. Gaunt, sullen, great sorrow and guilt absolutely written on her face, neighbors and relatives help her to her feet by as the camera zooms in. Others sit glumly, looking sullen and forlorn, staring into the camera.

A funeral service for an AIDS victim in the village. A close-up of faces. Young, well-cut cheek frames, but with death stalking. The villagers sing a funeral hymn, expressionless, yet there is so much beauty in the dirge. Beauty in deep sorrow. The villagers bury their dead, hoeing the dirt on the coffin.

The migration of people from the “back country” villages to regions or cities promising employment opportunities has depleted the population in rural areas. And those arriving at places like Mwanza and the Lakes and who do not find work as fishermen or factory hands end up scavenging for food and other bare essentials.

Prostitution is widespread around the Great Lakes region, and so is HIV and death by AIDS. In the village of Ito, M’Kono, an ex-school teacher and village leader, tells us, “Some people say the women in these parts are harlots, but it is not their fault, they are not to blame. They are forced to become prostitutes.” He explains that women, many of whom have lost their husbands and fathers (to AIDS and crocodiles in the lakes), are flocking to Mwanza and other towns in the area seeking to sell their bodies for a pittance. Poverty has gripped the nation and prostitution is the only alternative for many widows and orphans. “It is a vicious cycle,” he says about poverty, prostitution, diseases, and death.

“In the past,” M’Kono says, “there was a scramble for land in Africa by the great powers of Europe.” Nowadays, he declares, “it’s the scramble for Africa’s natural resources.” It’s a case of the “survival of the fittest,” M’Kono says. Talking of the fittest today, as it was in the past, it is the Europeans who are the strongest, and they come out on top. M’Kono observes, “It is the Europeans who possess the money, own the IMF, own the World Bank and the world trade.” It is they who bring in supplies of goods, profit from them and even benefit from the humanitarian relief aid. “It’s the law of the jungle,” he concludes.

Christian fundamentalism and hardship are obviously feeding into each other in the villages of the outlying areas. In a village nearby, a highly charged young man, well-fed and well-clothed, is holding a microphone in one hand, haranguing a gathering, gesticulating with boundless energy with the other. He hollers his praises to god and Jesus Christ, denounces the “devil” and calls on his parishioners to abstain from Satan’s temptations. He appears fierce, threatening, ending with a great Hallelujah! Amidst the extreme deprivation and squalor, it is clear that only the church has sophisticated electrical equipment. A film is shown of Jesus on board a fishing boat, hauling in a bountiful catch.

Reverend Cleopa Kaijaga, the village pastor, reveals that 45 to 50 or even 60 people die of AIDS every month in the area. In his small village alone 10 to 12 people have died of the disease monthly. As a pastor, he says dolefully, he advises the fishermen to stay away from prostitutes, and the womenfolk to keep away “from the business of prostitution.” The prostitutes seek out fishermen bringing in their catch every day. There is an air of despondency about him as he reflects on this—and this is really heart-wrenching—and yet unnerving. When asked if he would recommend the use of condoms, this preacher says no, claiming not only that condoms—the only means of prevention against HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases—are dangerous, but also that their use is a “sin against God’s law” and that instead women should abstain from sex outside marriage. This hard-sell brand of Christianity of the evangelical Protestant kind is a major export of the U.S. ruling class to these parts.

“The people here hope for war”

The immense sadness of watching infants and street-children so young lose their childhood, their innocence, is matched by the cynicism of Raphael, a retired soldier, now a fisherman by day and a night watchman at the National Institute of Fishery. He tells us how the previous watchman was hacked to pieces by thieves. All smiles now, and paid no more than a dollar a night at the institute for fish research, he calmly informs Sauper’s camera crew that he would readily shoot to kill (with his bow and poisoned arrows) any would-be burglar who dared enter the compound he is guarding. He muses aloud his regrets for being poorly educated and thus earning a very low income and yet being unable to rejoin the army owing to his age. And how things would turn for the better for him if war broke out once again.

Raphael tells Sauper that there are no hospitals or clinics around the place he lives and works. People needing medical care would have to travel great distances (to big cities) for treatment. Tanzania’s social services have been wrecked by imperialist-ordered policies. In order to extract debt repayment, from the 1980s through today, the IMF demanded that Tanzania slash state funding for health care and other social services, thereby making the people more vulnerable to chronic illness and diseases. The 2005 IMF report hails Tanzania’s favorable economic growth, an economic success story! This “success” has come at the cost of the poor becoming even poorer, a widening disparity of income and wealth, illiteracy, diseases and the death of so many young people.

Raphael tells the camera that war is good for the people around here. The army pays a good salary, he says, and takes good care of soldiers. “Many people hope for war here,” he adds. “Are you fearing war?” he asks Sauper. “I’m not fearing war,” Raphael adds reassuringly.

No amount of description can adequately do justice to Sauper’s Darwin’s Nightmare, which ends with a grim, but sad note: two very young boys taking turns to sniff into a bottle of glue and smoke a cigarette before they fall asleep in a dark alley as a motor-car speeds past a street light. This scene, like others, is never to be forgotten. Through his superb cinematography Saupert offers glimpses of how the European Union, IMF, World Bank and the very workings of international finance capital have wrought such dire consequences for a third world nation.

THE BASIS, THE GOALS, AND THE METHODS OF THE COMMUNIST REVOLUTION

By Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party

[Editors’ Note: The following is drawn from a talk given by Bob Avakian, Chairman of the Revolutionary Communist Party, to a group of Party members and supporters in 2005. It has been edited for publication here, and subheads and footnotes have been added. Previous excerpts drawn from the same talk have been printed in Revolution, most recently a series of excerpts with the overall title “Views on Socialism and Communism: A RADICALLY NEW KIND OF STATE, A RADICALLY DIFFERENT AND FAR GREATER VISION OF FREEDOM”—see Revolution #37, 39, 40, 41, 42, and 43 (March 5, 19, 26 and April 2, 9, and 16, 2006). “Views on Socialism and Communism” is available in its entirety at revcom.us.]

The New Synthesis: Not Utopianism, But Dealing With Real-World Contradictions

I want to move on now—everything that’s been spoken to so far forms, in one aspect, a kind of a background for this—to speak more directly and fully to the question: What is the new synthesis?

The first point that needs to be made is that this is something that is dealing with real world contradictions—it’s not some idealist imaginings of what it would be nice to have a society be like. When we talk about a world we want to live in, it is not a utopian notion of inventing a society out of whole cloth and then trying to reimpose that on the world once again. But it is dealing with real-world contradictions, summing up the end of a stage (the first stage of socialist revolutions)1 and what can be learned out of that stage, attempting to draw the lessons from that and dealing with real-world contradictions in aspects, important aspects, that are new. It is a synthesis that involves taking what was positive from previous experience, working through and discarding what was negative, recasting some of what was positive and bringing it forward in a new framework. So, again, it’s dealing with real-world contradictions—but in a new way.

In this connection, there is a point of basic orientation that is worth quoting from a paper written by a leading comrade of our Party:

“If we try to embrace, encompass and explore non-communist people, ideas and perspectives ever more widely and flexibly (which we should do) but do so on the basis of something other than a truly solid core and strategic grounding in OUR project and objectives, we will at one and the same time fail to harvest as much as we could from these wider explorations and initiatives AND, most unconscionably, we will LOSE THE WHOLE THING!”

Now, this has particular application with regard to the orientation and approach of our Party; but, in the broader framework of the larger world we need to be transforming, this also has more general application. And what’s being said here is an important aspect of the principle of solid core with a lot of elasticity,2 which is itself a kind of encapsulation, or concentrated expression, of what is involved in the new synthesis I am referring to. Not only now but throughout the struggle, to first seize power and establish socialism and then to continue advancing to communism—in other words, both before and after the seizure of power—the general principle of solid core with a lot of elasticity and the specific point that’s being driven home in what I cited above from that paper by a leading comrade will have important, indeed fundamental, application: the contradiction between on the one hand, yes, embracing, encompassing and exploring non-communist people, ideas and perspectives ever more widely and flexibly and getting the most we can out of that—not in a narrow, utilitarian sense, but in the broadest sense—but at the same time not losing the whole thing, not letting go of the solid core, without which none of this will mean anything in relation to what must be our most fundamental objectives.

Living With and Transforming the Intermediate Strata in the Transition to Communism

And this relates to the very real and often acute contradiction between applying the united front under the leadership of the proletariat—the leadership of the proletariat, and not of the petty bourgeoisie, or some other class—all the way through the transition to communism on the one hand, and on the other hand, actually forging ahead through that transition and advancing to communism. So “solid core with a lot of elasticity” relates to this very real and often acute contradiction, which in turn relates to the point that Lenin made when he said that the first and, in a certain historical sense the easier, step is to overthrow and to appropriate the bourgeoisie (to expropriate the holdings of the bourgeoisie). And if this is, in a certain historical sense, an easier step, the more difficult process is one of, as Lenin put it, living with and transforming the middle strata in the transition to communism. This is a very profound point, and both aspects of this are important; this is once again a unity of opposites—living with and transforming the middle strata. If you set out only to live with them, you will end up surrendering power back, not to the petty bourgeoisie but in fact to the bourgeoisie; things will increasingly be on their terms. On the other hand, if you seek only to transform the petty bourgeoisie (speaking broadly, to refer to the intermediate strata of various kinds), you will end up treating them like the bourgeoisie and driving them into the camp of the bourgeoisie, seriously undermining the dictatorship of the proletariat, and you will end up losing power that way, also.

So there is, as Lenin emphasized, the need to live with and transform these middle strata, these intermediate strata, both in their material conditions as well as in their world outlook—and in the dialectical relation between the two. This goes back to my comment earlier, speaking to three basic class forces, the bourgeoisie, the petty bourgeoisie, and the proletariat: the transition to communism aims to and must eliminate the basis for and the existence of all three of these groups, or classes, but the proletariat is the only one that doesn’t mind. The petty bourgeoisie definitely minds; it will continually strive to re-create its existence as a petty bourgeoisie and, indeed, will strive toward becoming the bourgeoisie, spontaneously. But you have to draw a clear distinction between the petty bourgeoisie (the intermediate strata) and the bourgeoisie, and not seek to exercise dictatorship over the petty bourgeoisie, which would drive them into the arms of the enemy—and, in that and in other ways, would work against our most fundamental objectives. (I will speak to that more fully in discussing the “parachute” point a little later.) On the other hand, you can’t simply allow these intermediate strata to follow the spontaneity of their own outlook and their own interests at any given time, or you will lose the whole thing that way.

As you move to uproot the soil that gives rise to capitalism and move beyond the sphere of commodity production and exchange—the law of value, the great difference between mental and manual labor, and all the production and social relations and the rest of the “4 Alls”3 characteristic of capitalism—you are going to run into conflict with the interests of intermediate strata. And how to handle that, through the whole long transition from socialism to communism (which, again, can only happen on a world scale), is going to be a very, very tricky question and one that’s going to require a consistent application of materialist dialectics, in order to be able to win over, or at least politically neutralize, at any given time, the great majority of these intermediate strata—and prevent the counter-revolutionaries from mobilizing them, playing on grievances they may have, or playing on and preying on the ways in which things that you objectively and legitimately need to do may alienate sections of the petty bourgeoisie at a given time. And here again there is a real contradiction—which can become quite acute at times—between the necessity that you are, in fact and correctly, imposing on the petty bourgeoisie, while not exercising dictatorship over it, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the countervailing spontaneity and influence of the larger social and production relations which exist and which you have not thoroughly transformed—and, along with that, there is the larger world, which at any given time may be mainly characterized by reactionary production and social relations and the corresponding superstructure. You are not going to be able to deal with all this in such a way as to not only maintain the rule of the proletariat but to continue the advance toward communism, unless you can correctly handle the principle and strategic approach of solid core with a lot of elasticity.

In this regard we can say that there is a kind of application, under the conditions of the dictatorship of the proletariat, of an important formulation in Strategic Questions4—which I won’t try to fully elaborate here, but it has to do with drawing dividing lines so that, at any given point, you unite the greatest number of people around positions which are, to the greatest degree possible, in the objective interests of the proletarian revolution, while at the same time winning as many as possible subjectively to that—or, in other words, winning as many as you can to be partisan toward the goal of proletarian revolution—without undermining the necessary unity at any given time. You can see that’s another “moving target”—it’s a living dynamic and a contradictory thing, sometimes in acute ways. And, in socialist society itself, particularly with regard to the middle strata, but more broadly and even among the proletarians, there is an application of that principle spoken to in Strategic Questions. But if you let go of the solid core, none of this would be possible. In terms of the four objectives I referred to earlier, in relation to the solid core in socialist society—including the importance of having the maximum elasticity possible at every given point—if you let go of the first point, holding onto power, none of the rest of it has any meaning.5 So we can see how there is tremendous tension—or, another way to say it, there is very acute contradiction—involved in all this.

And, as I have spoken to, this involves a whole epistemological dimension as well as the political dimension. It involves the question of how not only the communists but the masses of people broadly actually come to a deeper and richer synthesis of the understanding of reality in any phase of things, through any process, and in turn have a stronger basis for transforming the world—without giving up what you’ve got at any given time, without letting go of the core of everything. This is what causes me to continually invoke the metaphor of being drawn and quartered.6 If you think about this—if you actually try to think about this image of standing there at the core of all this, unleashing all this intellectual and political ferment in society, while at the same time you are seeking to bring into being certain material and ideological transformations that move toward communism and which run up against spontaneous inclinations, even of proletarians, and run up against certain vested interests of intermediate strata, and, of course, run fundamentally up against the bourgeoisie and the imperialists and other reactionary forces—you’re trying to do all that and (continuing the image) you’re holding on to the reins with each hand while people are running in all kinds of directions. If you really think about all that, you can see why I continue to invoke the metaphor of being drawn and quartered, if we don’t handle this correctly. But I am equally convinced that, if we don’t proceed in this way, we are not going to get, within the socialist country itself, the kind of process we need in order to get to communism (leaving aside for a minute the whole international dimension, which I will come back to).

Now, this principle of solid core with a lot of elasticity—and elasticity on the basis of the solid core, let me emphasize that once again—has to do with, is closely bound up with, another principle which is discussed in the talk on the dictatorship of the proletariat:7 namely, the great importance of distinguishing between those times and circumstances when it is necessary to pay finely calibrated attention to things and to insist that they be done “just this way,” and, on the other hand, those times and circumstances when it is not only not necessary to do that, but it would be harmful to do that. In the experience of our Party, for example, there have been various times and circumstances when it was necessary to pay very finely calibrated attention and insist on things being done exactly this way and not that way—and, along with that, to insist on things being very tightly in formation, so to speak. But then there have been many other circumstances where that has not been the case, and where to insist on this would be wrong and harmful. For example, relatively recently we have had debate about the Party Programme, inside as well as outside the Party, and we have had other processes in the Party where there have been debate and struggle over questions of line. This is not, and should not be, just a one-time or infrequent aspect of things—it is something that should find expression repeatedly, in the appropriate times and circumstances, in the ongoing political and ideological life of the Party.

As I pointed out in that talk on the dictatorship of the proletariat, this relationship between “opening up” and “closing ranks” and between elasticity and solid core, is also a dialectical process, a unity of opposites. What is solid core in one aspect also has elasticity within it as well. There is no such thing as a solid core that doesn’t have some elasticity within it. At any given time (as well as in an overall sense), there are always those things to which you are paying finely calibrated attention, but other aspects of the same thing to which you are not paying the same systematic attention.

In that talk on the dictatorship of the proletariat, one of the examples I used was writing an article. It’s not that you don’t care about certain things you say, but some of them you have to get exactly right, because they bear on the whole character of what you’re saying, while with other things, you say them as best you can but you do not—and actually should not—pay the same amount of attention, or you’d never finish writing, for one thing. And in anything you do—in a meeting, for example, and more generally in everything you do—this principle applies: solid core with elasticity and paying finely calibrated attention to some things that are at the core and give definition to everything you’re doing, while not trying to pay the same kind of attention, and allowing a lot more elasticity, with regard to other things.

And with regard to the aspect of solid core itself, you can’t say, “well, we have to have an absolute, perfect solid core before we can allow for any elasticity and initiative.” On the other hand, there is a real problem if the elasticity is not, in a fundamental sense, on the basis of the solid core—if, in effect, the elasticity and the initiative that is taken amounts to, or results in, substituting some other solid core for the one that is actually, objectively needed. But, again, you can’t get metaphysical and “absolutist” about this: You can’t say, “only when we have some ‘absolute’ solid core, and everybody has exactly the same level of understanding and agreement with regard to that solid core, can we then have any elasticity.” First of all, you’ll never achieve that kind of absolute certainty and absolute unity, you’re never going to overcome all unevenness; and second of all, your solid core will dry up and turn into its opposite, into dogma. It will become lifeless and turn into its opposite, and it won’t even be a solid core any more, in fact. There has to be space and life, even within a solid core; there are certain solid core things within any solid core, around which other things, within that solid core, are less solid and have more elasticity, if you will. (This is another expression of the very important point made by Mao, which I have emphasized a number of times: what is universal in one context is particular in another, and vice versa.) But if you don’t have sufficient adhering power, so to speak, at the core, so that (to use this metaphor) the electrons are flying off in every direction, then you have a serious problem.

Once again, we can see that crucially involved in all this is that fundamental dividing line between materialism and idealism, and between dialectics and metaphysics. You can’t have a metaphysical view of what a solid core is, and somehow it has to be absolutely solid; at the same time, you can’t have an idealist view of the whole process which corresponds to people going off in all directions because there’s no material grounding in terms of what the solid core is and has to be in any given set of circumstances, and in terms of what are the things where you have to insist on their being done in a certain way, with everyone “marching in tight formation,” so to speak, and on the other hand what are those things where you not only should not do that but where it would do real harm to try to insist on that.

And, speaking frankly, among the ranks of the communists—this applies to our Party but also more generally to the communist movement—there is a need for a further leap and rupture beyond utopianism and idealism and, frankly, beyond social-democracy or even outright bourgeois democracy and, ironic as it may sound, even plain old, straight-up anti-communism within the communist movement itself, which takes expression particularly in what amounts to a bourgeois-democratic view of such crucial things as the nature and role of the state and a bourgeois-democratic critique of the historical experience of the proletarian state. We need to leap and rupture beyond and out of those confines, even while we also need to rupture more thoroughly with the “mirror opposite” of this: the tendency to dogmatism and essentially a religious view of the principles and of the experience of communism and the communist movement, which amounts basically to “all solid core” with no real elasticity—and, correspondingly, to a “solid core” that in the final analysis is not all that solid, is in fact brittle, because it is grounded in apriorism and instrumentalism (seeking to impose dogmatic conceptions on reality and to “bend” and torture reality to make it serve certain preconceived notions and certain aims—not to engage reality and transform the actual necessity that has to be confronted, in accordance with its fundamental and driving contradictions, but to apply one variation or another of what Lenin criticized as the approach of “truth as an organizing principle,” which amounts to a subjective and idealist notion of truth rather than a recognition of truth as something that is objective and that is characterized by its being a correct reflection of objective reality). Still, while we must reject an orientation and approach that amounts to “all solid core,” at the same time we cannot have a utopian and idealist view of what elasticity means—treating it as something unmoored from the actual underlying material relations of society, and the world, in which all this is embedded, a material reality which we are seeking to transform, but can’t simply transcend in our minds.

The correct application of this principle—solid core with a lot of elasticity—is elasticity on the basis of the necessary solid core at every given point. And I say the necessary solid core because, again, dialectics enters in: it is not a matter of some absolute solid core, because that would be metaphysics—conceiving of and aiming to achieve some perfect state of solid core, which in fact you never will achieve—but it is a matter of the necessary solid core: enough of a solid core so that it acts as a powerful cohering center and basis on which you can then proceed to move forward and unleash the elasticity and the initiative, without losing the whole thing. And there’s no “magic formula”—or, in a basic sense, no formula of any kind—for that. There’s no formula. You can’t get out a “sliding calculus” and say: at this stage of socialism, we need 28% solid core, and you can have 72% elasticity; but at this stage, once there is an imperialist intervention and invasion, we can only have 4% elasticity and 96% solid core. That’s not how it works. [laughter] These are living, moving things that we have to be scientifically engaging and dealing with and determining concretely on the basis of actually grasping the motion and development of the defining and driving contradictions.

***************

The “Parachute” Point

What has been said so far, concerning “solid core with a lot of elasticity,” relates very closely to the next point I want to get into, which is the “parachute” point: the concentration of things at the time of the seizure of power, and then the “opening out” again after the consolidation of power.

This is a general principle as to how revolution goes, and it also has more specific application to a country like this, and this country in particular. Whatever the path to power in a particular country—whether, in broad terms, the revolutionary road is one of protracted people’s war, where that is applicable, which involves surrounding the cities from the countryside and then eventually seizing power in the cities and thereby in the country as a whole; or whether the revolutionary road involves, as it does in imperialist countries like the U.S., a whole period of political (and ideological) work and preparation and then, with the emergence of a revolutionary situation, a massive insurrection, involving millions and millions of people, centered and anchored in the urban cores—either way, at the time when countrywide political power can be seized, things become “compressed” politically. A lot of the diverse political trends and currents that are in opposition to the established power either become politically paralyzed and/or they become compressed in and around the one core that actually embodies the means for breaking through what needs to be broken through to meet the immediately, urgently felt needs of broad masses of people who are demanding radical change. This happens specifically and in a concentrated way when that need to break through to actually seize power is not just some sort of long-term strategic objective and consideration, but becomes immediately posed; when, along with that and as part of that, other programs which are seeking social change become paralyzed in the attempts to implement them—run up against their limitations which, on a mass scale, causes people to reject them and to rally from them to the one program that actually does represent the way to break through.

Things tend to become compressed at that point, as when a parachute closes up. And one of the things that has not been sufficiently understood—and has led to mistakes, in its not being correctly understood and dealt with—is the fact that, while this is a very real and important and necessary ingredient, in an overall sense, of actually being able to have the alignment that makes it possible to go for revolution, this is something that comes into being at the concentration point of a revolutionary situation but not something that will continue in the same way after that point has been passed, regardless of how that situation is resolved—not only if the revolutionary attempt fails or is defeated, but even if it is successful and results in the establishment of a new, radically different state power. Even then, after that situation has passed, and as things go forward in the new society, the “parachute” will “open back up” and “spread out.”

This relates to Lenin’s third condition for an insurrection—that a situation develops in which political paralysis qualitatively weakens half-hearted and irresolute friends of the revolution. Other forces, representing the interests of social strata other than the proletariat, and programs corresponding to that, are paralyzed or incapable of speaking to the needs and demands of masses of people and what’s posed, very acutely, by the objective situation. When that occurred, for example, in the Russian Revolution in October 1917, people in huge numbers rallied to the Bolsheviks. And in that situation, as the revolutionary crisis assumed its most acute expression, there was that dramatic moment when one of the Mensheviks (reformist socialists) said at a mass meeting, “there is no party here that would lead a struggle for power”—and Lenin rose and declared emphatically: “There is such a party!” And Lenin and the Bolsheviks were able to win people to that. But this does not mean that all the people that they won, at that decisive moment, were won in any full sense, or anything close to it. That is, they were not necessarily won, in their great majority, to the full communist program. While some were won to that, for a far greater number it was more that, at that acute moment, the program of the Bolsheviks, and of no other force, represented the only way out of a desperate and increasingly intolerable situation.

So here is where, after power is consolidated, “the parachute opens back out.” In other words, all the diversity of political programs, outlooks, inclinations, and so on—which reflect, once again, the actual remaining production and social relations that are characteristic of the old society, as well as what’s newly emerging in the society that has been brought into being as a result of the revolutionary seizure and consolidation of power—all these things assert, or reassert, themselves. And if you go on the assumption that, because people all rallied to you at that particular moment when only your program could break through—if you identify that with the notion that they’re all going to be marching in lockstep with you and in agreement with you at every point all the way to communism—you are going to make very serious errors. This is a very important point in general in terms of revolution and, obviously, would have particular and important application in a country like the U.S. And, obviously, this relates to solid core with a lot of elasticity, because everything is going to get pulled more toward that revolutionary core at the time when everything is compressed like that—and then many things are going to move back out, away from that core, in a certain sense.

This is an important dimension in which the whole question of living with and transforming the middle strata asserts itself, and poses the kind of contradictions that I’ve been talking about. On the one hand, there are the basic proletarian masses and, within the broad ranks of those masses, there are those who are most advanced and class conscious in their understanding, who are most firmly supporters of and fighters for the revolution, and who most deeply understand the overall objectives of the revolution and the final aim of communism; and then, along with those advanced proletarians, there are intermediate and backward, even among the proletariat, and there are broader strata of people (within which there are also advanced, intermediate, and backward). And once again, to continue advancing toward the goal of communism, which involves a whole long period of transition, you have to know how to handle all these different dimensions and levels of the “social configuration,” if you will, all the different expressions of the underlying contradictions that are giving rise to this. Ideologically, politically, and in terms of the economy and economic construction, as well as in terms of defending the socialist country while at same time supporting the world revolutionary struggle, you have to know how—here’s another application of solid core with elasticity—you have to know how at one and the same time to (a) hold on firmly to power and keep going in the direction of communism, while (b) giving expression to, and making the most of, all positive factors of all the different forces and diverse strata among the broad category of the people in society, while handling correctly the negative aspects that go along with that, from the standpoint of continuing the socialist transition toward the goal of communism (which, once more, can only be achieved on a world scale).

Here again this involves great complexity: The core, at any given time, whatever that core is, is holding all this in its hands, so to speak, and has to see the broad panoply of all this and, at least in their basic outlines, all the gradations that lie within this, and know how to handle it all in a “textured way,” if you want to use that metaphor. You have to handle correctly all the complexities of this while keeping it all going where it needs to go—continuing the revolution toward the goal of communism. You see, it’s not “head down, march straight forward”; it’s like this [waving his hands in circles to give expression to all the complexity], with all these different things going on, often in different and contradictory directions, within this whole process. That’s what we’re talking about dealing with, and if you try to compress that back down to what it was like at the time of the seizure of power, you’re going to lose power, lose the whole thing, one way or another, because you will not be able to do that. On the other hand, if you let it all go where it wants to go [laughter]—if you let it all go where it wants to go, then you’re going to lose everything in that way—because it’s going to go back into that spontaneous striving to come under the wing of the bourgeoisie,8 in one form or another. And this is not existing in a vacuum, but in the actual conditions of what socialist society is like, with its material and ideological “left-overs” from capitalism—with the continuing existence of different classes and strata, and their underlying material basis in the production relations, with the corresponding social relations, as well as the expression of this in the political and ideological superstructure—and the international context that all this exists within, with the existence of remaining imperialist and reactionary states and the very real dangers and threats this poses to socialist states that are brought into being through revolution.

We can see the negative, extremely negative, expression of not correctly grasping and handling this in the experience—which I won’t attempt to go into in any kind of full way here, but briefly—the experience of Pol Pot in Cambodia, where instead of this kind of approach they had this whole approach that involved real irony, as well as real disaster. They had peasant masses who had not undergone any real radical transformation in their thinking, despite certain changes in their material conditions: the peasant masses, especially in the base areas they established during the war against the Lon Nol regime and the U.S. (which installed and backed that regime), were led by intellectuals who had that problem, the very real problem that I’ve spoken of in other talks and writings—the phenomenon of education on a narrow foundation (I’ll come back to that point shortly, because it is actually a very important point). And the Khmer Rouge, under Pol Pot’s direction, took the rest of Cambodian society and attempted to pound and flatten it down to the level of the peasantry—as the peasantry was then—in the name of, and somehow as a supposed means for getting to, communism. To wildly understate it, they did not grasp solid core with elasticity or the “parachute point” at all. And this led to real disasters and, yes, real horrors.

The Danger of Education on a Narrow Foundation

Now, to turn more directly and fully to this point about education on a narrow foundation: I was reminded of this point again in seeing the presentation by Raymond Lotta on Setting the Record Straight—and specifically the discussion of the Soviet model of bringing up “a working class intelligentsia.” Besides the very real, and very significant, problem of mechanically identifying class origin with class outlook—which was a very marked tendency with Stalin but also found some expression in China under Mao’s leadership, although Mao was far more dialectical than Stalin about this, and in general—besides that problem, what was the essential aspect and the focus of that “working class intelligentsia” in the Soviet Union? Engineers. Now, I know that it’s probably not fair, and I don’t want to single out engineers as the only ones representative of the problem, but they are, I’m afraid to say, sort of a good metaphor for the problem. I have actually known engineers who became communists—but there’s still something about engineers, I’m sorry. [laughter] And there is definitely something about education on a narrow foundation, even if the education is in “Marxism.” If it’s education that amounts to training in dogma, which does not recognize and deal with the complexities of things—and all the different realms of society and history and nature, and yes, of epistemology, that have to be dealt with in order to actually lead this kind of complex process of revolution—if people trained in that kind of “education on a narrow foundation” emerge as the leadership, and if that leadership then takes basic masses as the main force it is mobilizing and relying on, but takes them more or less as they are, and uses them as a battering ram in relation to all the other strata in society, it becomes a very, very bad and dangerous brew, a poisonous brew.